Visiting Tibet: From Dharamsala to Lhasa (1962-1998)

Being in my mid-sixties, I am no longer young. I often reflect on my past life, the people I have met, and the experiences I have had. So far, I feel I have had a lucky and happy life. A child in World War II, I was alerted early on to the fact that humanity can be evil and cruel, just as it is also kind and loving. I used to have childish dreams of going to Hitler and asking him to change his views and make peace with all peoples. I always had the feeling that I could have been born anywhere in the world and that it was a lucky chance that I had 'landed' in England which has not suffered occupation by a conquering power with the attendant brutalities and suffering. I felt that I might just as easily have been born Jewish in Germany or elsewhere in Europe. I sensed something of how terrifying that could have been; how I could never have felt safe and free from underlying fear. I have always pondered these things and felt flooded with relief and gratitude for a life in a democratic and generally kind society.

As I grew older I believed in the French adage "The price of liberty is eternal vigilance". I realised that it was not only in Europe that tyrannical things happened. I felt horror at the Korean War, Vietnam, South Africa, Palestine, Angola... Then one day at a meeting of the Buddhist Society in Cambridge, I first heard of Tibet and the plight of the Dalai Lama and his people.

Although I had originally trained as a nurse, I never had much confidence in my abilities and felt helpless in the face of so much oppression everywhere. Yet I dearly wished I could do something. I now realised that there was no way I could visit a dictator and ask him to stop what he was doing! But the idealism of my childhood remained dormant.

I heard of the Service Civil International, an organisation working for peace and reconciliation with its headquarters in Switzerland. This organisation had originated through the work of Swiss Quakers at the end of the First World War and young people of several nationalities, French, English, German, some of them former enemies, went to help rebuild villages in both France and Germany. Their motto was "Peace through deeds not words."

They were prepared to work anywhere and together with anyone, provided they did not take paid work away from anyone. Their own work was minimally financed with a travel allowance and a minute amount of pocket money. Workers lived with the people they were assisting. Such projects were commonly in emergency situations or where extra hands were required. Often the longer- term work was 'trouble shooting', investigating problems, preparing reports and attempting to attract funds and a workforce. The main aim was the creation of a community of people from different nations, particularly coming from those where there had been legacies of hatred and fear. This was not an aid-giving organisation such as the Peace Corps (which was then just starting). Exchanges of people to work in different countries were common and took place regardless of the economic situations in different lands. Thus Indians and Japanese would come to England and we would go to their countries.

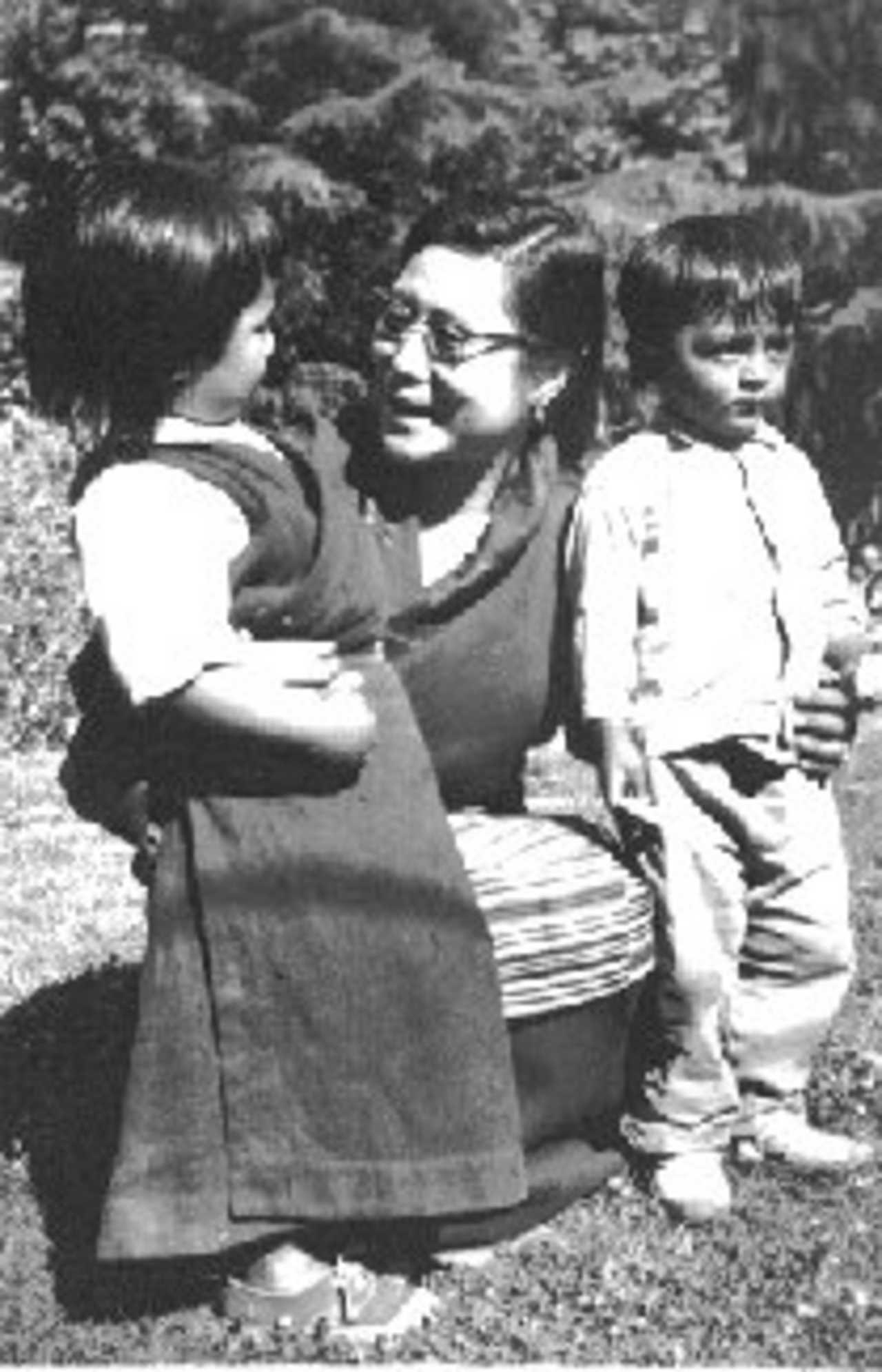

Working in Dharamsala, 1962 I was so impressed with SCI that I eventually took a deep breath and volunteered to work with them. In 1962 I found myself in India travelling to a place called Dharamsala! I was met at McLeod Ganj (or 'Mudly ganj' as the Tibetans pronounced it) by Mrs Tsering Dolma, the elder sister of the Dalai Lama. We walked up the mountain for about half an hour because the only way to reach the 'nursery' of refugee children was by foot. Dharamsala nursery was a large house with a red tin roof surrounded by the dense forest of the Himalayan foothills. It could once have been beautiful, a British Raj house no doubt. But now it was rough and untidy and the 'garden' was simply hard packed earth.

There was a second house nearby. Some one thousand refugees, mainly children, lived there. Two hundred boys slept in one room, arranged with bunk beds all around the walls and with mattresses covering the floor. The boys slept crosswise to a mattress seven on each one of them. The girls slept in smaller rooms in similar conditions.

Overcrowding was rife and of course infections spread like wildfire. Tibetan children were used to the relatively germ-free conditions of the Tibetan plateau and were vulnerable to the diseases of the Indian plains especially while travelling across them to reach Dharamsala. They had no immunity to the diseases of a hot climate. Many children died during a measles outbreak and from hepatitis from infected water (I also eventually got jaundice while I was there). Most children suffered from scabies, eye and ear infections, worms, dysentery. Many got pneumonia and other respiratory infections.

For a brief time there was no doctor, but for most of the time a Swiss Red Cross doctor lived down the mountain and she could be visited with a sick child. There was a severe shortage of drugs and medicines. We had to work within the sad realisation that there were limits to what was possible in the short term. In the longer term the Ockenden Venture, SCI, Swiss Aid to Tibetans, Save the Children Fund, and the Indian Government gradually offered help and children moved to other establishments (some to Europe) which reduced the crowding to manageable proportions.

My time at Dharamsala overlapped for a while with the presence of Doris Murray, a teacher sent by SCI to help with educating children. She was an enormous help to me, especially on my first arrival. Unlike myself she had been in similar working conditions previously and had built up her confidence about medical matters even though that was not her official work. I regret that we lost contact later on.

In those days no one went hungry. The Indian Government was very supportive. We had plenty of rice and vegetables. Yet, when I left, I realised I had not eaten meat, fish, eggs, cheese or fruit for a long while. I do remember the Post Office man in McLeod Ganj giving me a fried egg on toast to eat one day when I went there to buy stamps. That is India for you!

The Indian Gadi people, semi-nomads who wander the Western Himalayas with their great flocks of herds and goats, used to visit with meat for sale. This was usually a live animal. I loved the Tibetans for their response to these visits. As Buddhists they do not kill sentient beings and this was strictly observed in Dharamsala. One day they purchased a ram in order to save its life. It became one of many pets and I was often awoken by the loud crash of the ram's horns on my door, and the animal would come galloping in with a loud baa-baa-ing! When I myself fell ill with jaundice, I remained in bed waiting for it to pass. I thought that eating some liver might help me recover. When I heard that some Gadi people were outside offering dead meat for sale (chops, offal etc.) I enquired whether on health grounds the Tibetans would feel it alright to get me some liver. This they did but they had no idea how to cook it. The whole liver was boiled in one piece and proudly presented to me on a plate. It was delicious! When I was very ill, Mrs Tsering Dolma allowed me to sleep in the Buddha room where butter lamps were always burning. It was so peaceful there.

When the Tibetan doctor (an 'amchi'), with whom I had been trying to develop a good liaison, heard that I was ill, he came and asked if I would accept his medicine. I agreed. He told me that I was very ill (and indeed I was very yellow) but that by a certain date the illness would be gone from my body. In fact, on that day, I went for a check-up at Kangra Mission Hospital and they confirmed that there was now no trace of the illness.

I learned how important it was to have good relations with other professionals including those from another culture. There was a need to drop the idea that only Western ideas were 'right'. The Red Cross doctor had become very angry with the lamas who had visited our little hospital room where the youngest and most sick children were. The lamas were chanting mantras and wafting smoking juniper branches in the air as incense. Understandably the doctor felt that smoke was bad for children with pneumonia so she sent the lamas abruptly away with no explanations. As a result of this ham-fisted action the young Tibetan girls who tended the children daily began to hide some sick children from the doctor. They had a greater faith in the lamas of their own culture than in Western approaches to health care. This led to serious situations.

Mrs Tsering Dolma was most concerned lest Westerners who occasionally visited showed too much affection to the children. This seemed hard but her point was that the children had to come to terms with their reality. She felt that for a child mourning the loss of its parents to be given loving care and affectionate hugs for five minutes, only to watch the departing back of a visitor soon after, never to return, the experience would be too painful and best prevented. Yet my heart was broken several times when I watched a small figure searching here and there and then running away to the mountain crying again and again "Ama Ama!" (Mother, mother). Once I awoke to find that a thin little boy had crept silently into my room and lay asleep on the floor beside me. I had been treating him the day before, and I believe he was desperate for mothering.

Many of these children were orphans, their parents having died during the Chinese occupation of Tibet, or they had been sent out of Tibet by parents who had stayed but felt their children would have a greater chance of life if they went to India. Other children did have parents in India but who were often working under such hard conditions, such as chipping stones for road making in the mountains, that they could not have their children with them. All Tibetans would wish themselves or their children to be near the Dalai Lama.

The Dalai Lama lived a short walk away from us along the mountainside. I sometimes visited his place to meet Mrs Tsering Dolma and his niece. At one ceremony I was blessed by the Dalai Lama with a khatag (white scarf). Another time Mrs Tsering Dolma gave me a holiday by taking me with her to Dalhousie where we went horse riding together. I felt very privileged. When interpretation was necessary I had the help of a young girl who had recently left school. Her name was Kesang and I have only recently realised from reading the Free Tibet magazine that she was Kesang Takla, the recent representative of the Dalai Lama in London.

Pilgrimage to Kailash, 1997 After four years abroad I returned to England and realised that I was more concerned with social problems than I was with medical ones. I retrained as a social worker. Now I have officially retired and my life begins to feel somewhat self-indulgent. When I heard about my brother's planned pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, the famous Tibetan holy mountain hidden in a remote area of high altitude behind the Himalayas in western Tibet almost due north of Dharamsala, I planned to make this into a personal one-month sponsored walk. The pilgrimage would take us on foot to Tibet right over the high ridge of the Himalayas by way of the formidable Lhagna-la Pass in Humla, west Nepal and then on again around the mountain. Using my Christmas card list I managed to raise £1330 for this project. I would have to complete the designated journey solely on foot.

In fact the trek proved unexpectedly strenuous as the Tibetan winter arrived earlier than expected. Temperatures in camp were well below zero on many nights and we often walked through snow blizzards especially during our attempt to go around the mountain. I had to conquer very real fears on precipitous snow covered tracks, altitude exhaustion and fatigue. We failed to circumambulate the mountain because of heavy snow, even the local Tibetans refusing to take their yaks around to help us due to the danger of them breaking legs in the snow-covered gaps between boulders. Two incautious Germans, attempting to go round without a guide, died on the mountain while we were there.

After our attempt we visited a Rimpoche, the abbot of a small monastery on the route back through Nepal, who told us that it was the fortitude of our attempt rather than succeeding in easy sunny weather that was the important thing. Even people of great wisdom had a hard time on the mountain, he told us!

It was good to see the nomads of the Tibetan plateau with their strange spider-like tents, their herds of yaks and goats. Their way of being seemed to epitomise the freedom which should be the right of all Tibetan peoples. If it had not been for the occasional Chinese police post we could have experienced this wilderness area as being quite free of foreign influence. Except at the border crossing, we did not meet any Chinese on our journey. Yet, at the ancient ruined city of Tsaparang, we ran into a Government party. One of the Chinese officials looked pleased to see me and asked me from where I came. I asked him the same question in return. He replied "China". Without thinking, I said "Are you visiting Tibet or do you live here?" From the way I asked the question he must have understood that I thought of Tibet and China as two countries. I myself had not realised the implication of my question until I saw him avert his eyes, drop his head to one side and, without replying, walk on.

Trek to Tibet, 1998 Recently, in 1998, I again had an opportunity to visit Tibet, trekking there through the late monsoon rain of Nepal through forests infested with leeches. We used the base camp at Mount Everest on the site from which Mallory and Irvine had left for their attempt on the summit, never to be seen again. That mountain is huge! The vast ice wall took my breath away. It is important at such places to stop to feel the 'spirit of place' that dwells there. So many make so much noise in their chatter that they never feel it. There is a silence in all such places - one night near Shigatse in Tibet I looked up at such a moment and counted fourteen shooting stars in the space of five minutes.

Once over the mountains into Tibet the sun shone again from fresh clear skies; the puffy balls of white clouds, so familiar from Tibetan art, casting ever-moving shadows across the vast ranges of a brown, desert-like landscape. From the frontier we took a four-wheel drive vehicle and visited small monasteries en route for Lhasa, Shigatse and other places far to the east of our previous journey. I found myself getting increasingly depressed. Whereas last time I had experienced the warmth of the Tibetans and their sense of hope as the monasteries were being restored and monks returning (albeit with Chinese authorisation), this year, nearer Lhasa, everything felt very different. Even the villagers seemed keen only to beg for money, directly asking for it, and seemed to be interested in us only for that reason. The directness of human contact felt missing here. The children followed us begging even into the holy places and no monk came out to greet us. Even the larger monasteries at Sakya and Shigatse had the same cold feeling.

What makes the centre and the West of Tibet feel so different today? I do not know. Have the Chinese been more brutal in the central areas or are Western tourists to blame? Maybe too many tourists have offered money to villagers and children. On this main tourist route under strict Chinese control maybe begging is the only contact possible. Or was I myself different this year?

Even so it was moving to visit Lhasa. In Dharamsala, all those years ago, the children had painted pictures of the Potala again and again. Now I was actually seeing the Potala for myself. Like Everest it is huge. It felt quite wrong that while I could walk those endless corridors, see the meditation rooms, and enter his living quarters, the Dalai Lama himself was unable to live in his own house. It was the same in the Summer Palace which he loved so much.

There are many Chinese living around Lhasa. Chinese farmers and business people outnumber the Tibetans. We stayed in old Lhasa not far from the Jhokang, but even this hotel was run by Chinese with Chinese staff. I felt most joy in and around the Jhokang monastery. Here the Tibetans wore their own clothing, hairstyles and jewellery with pride. The place was full of people practising their devotions, prostrating before the great front doors, filing along the corridors murmuring mantras and worshipping before the main figure of Buddha. This is a 7th century statue damaged in the Cultural Revolution. Before he died, the late Panchen Lama found the missing upper part of the statue in China and brought it back. Artist monks have now come to begin repainting the statue in gold. Butter lamps burnt brightly, monks were buzzing around smiling, communicating easily with one another and with us. There was an enthusiasm in the air. Once more I experienced the warmth of the Tibetans and began for the first time to relax. A group of monks began passing me on their way to bless the repainting of the statue. But then my sinking heart noticed that they were headed by a Chinese policeman in full uniform. Even here, in the depths of the Tibetan's holiest monastery, the necessary stamp of authorisation was being made only too apparent.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 1999 Other Articles Elizabeth Crook Others

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2025. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors and the views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-257