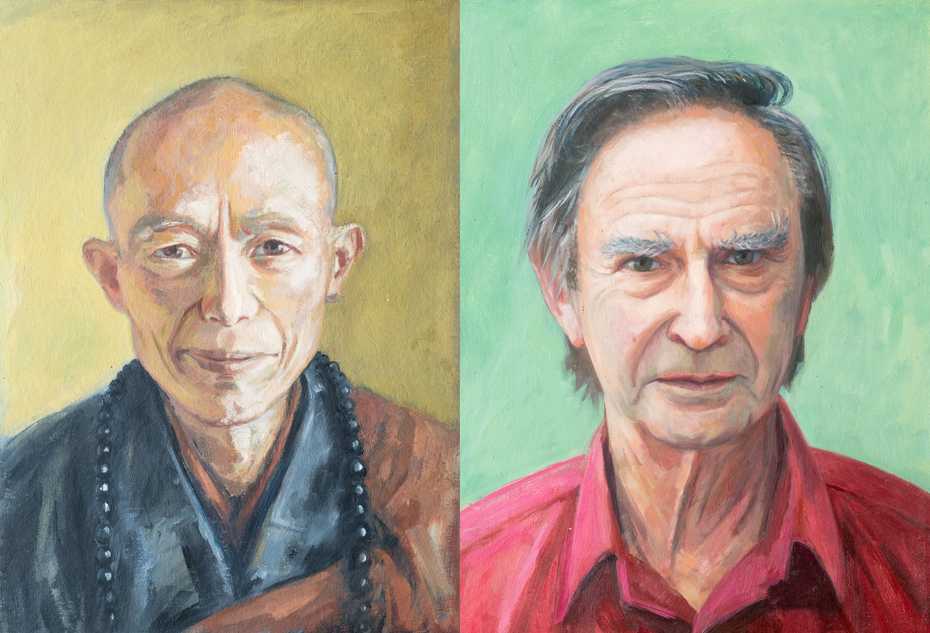

The Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen

A Brief Obituary

Chuan-deng Jing-di, John Hurrell Crook

On February 3rd 2009 at 4:00pm Taiwan time, the Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen, passed away peacefully at Dharma Drum Mountain Founder's Quarters in Taiwan thus bringing to an end the life of perhaps the most influential Chan (Zen) master of our generation. At centres all over the world, communities are mourning the loss of their Teacher - 'Shifu'.

Shifu's health had been declining over the past three years. This rapid decline started from the time of the inauguration of the Dharma Drum Mountain World Centre for Buddhist Education, Taiwan, in late 2005, when Shifu received surgery to remove a non-functioning kidney, and the remaining kidney's ability to function became very poor. Since then, he had been going through weekly dialysis and various other treatments, making his body very weak. Over the following two years, his health condition has had ups and downs, and remarkably, in mid to late 2008, Shifu had been noticeably stronger and able to give many lectures and attend many public events. However, in late December, a routine check-up at the hospital revealed a problem. Yet, Shifu kept on with his agenda. Shortly after, he was hospitalized and his health deteriorated rapidly. His condition looked grave. After a few days it took a turn for the better, and there was a visible improvement. Afterwards, Shifu continued to attend meetings and receive guests and also took a leave of absence from the hospital to visit the local Taipei monasteries and centres. Yet, soon his condition again deteriorated, fluctuating between good and bad. He returned to his home in the monastery that he had founded and passed away.

In 2008, Shifu published his autobiography in English carefully prepared by his closest disciples1. Here we read of a man who, like His Holiness the Dalai Lama, always considered himself to be a simple monk but who has accomplished a remarkable renewal of Chinese Zen Buddhism in Chinese communities throughout the world and extended its teachings to the West. His many books have augmented and corrected the earlier Western Zen understanding based on the previous contribution of Daisetz Susuki. Together with other masters such as Thich Nhat Hahn, Shunryu Suzuki and Jiyu Kennett, Shifu has created a Zen renaissance world wide thereby continuing the work of that great reformer Master Hsu-yun of the twentieth century in China itself.

Sheng Yen was born in 1930 near the estuary of the Yangtze River. Floods destroyed his father's lands and the family had to rely on a very small property and on fishing the river. This was a life of poverty soon to be made more difficult by the Japanese invasion of the area. As a boy, an old monk asked him whether he would like to be a monk. Although he had no idea what that meant, he grasped the opportunity and some time later went to school even while battles flamed around. Eventually he became a monk at a well-endowed monastery, Wolf Mountain, near Shanghai. Here he became enamoured with the Dharma with some insight into its significance. Soon however came more trouble and the eventual arrival of the communists. The monks, forced into poverty, kept going by offering funeral services in Shanghai. They received no training. Finding the only way out, Sheng Yen eventually joined Chiang Kai Shek's nationalist army and was thus able to move to Taiwan.

In Taiwan after the usual military training, square bashing and so on, Sheng Yen became an officer in the Intelligence Corps. Although he had no understanding of the implications of the telegraphic material he was handling, the military would not let him resign his commission lest he betray national secrets. He began developing his practice in his spare time and visiting monasteries. Eventually he was able to go back to civilian life. On one occasion in desperation he sought the help of old Master Ling-yuan in whose helpful presence he relieved his mind and experienced 'seeing the nature' for the first time. Gradually he became known and through working on a Buddhist magazine eventually he joined a monastery mastered by the eminent monk Dong-chu who had previously been the Abbot of the famous Jian Shan monastery on a riverine island near Shanghai. Dong-chu taught him through vigorous confrontation, giving him pointless tasks to do testing his resolve and will. It was much like the ferocious way in which the Tibetan Marpa had taught Milarepa.

Shifu eventually undertook a six year solitary retreat in the mountains beginning with a long period of repentance leading into study, learning Japanese and developing a determination to study Buddhism at a university in Japan, there being no place of advanced Buddhist learning in Taiwan. He obtained his Doctorate at Rissho University but also undertook gruelling retreats in Japanese sesshins where his learning was ridiculed in true Zen style. He developed the wish to take Zen to the West but had his doubts because he knew no English. "Ha," said his Master, "Do you think Zen is taught by words?"

Shifu found a sponsor and began teaching in Toronto and New York. But his sponsor was disappointed. Shifu had less English than he expected and other disappointments between them flourished. Eventually a friend, C.T. Shen, arranged for him to live at the Temple of Great Enlightenment in the Bronx, New York. Although Sheng Yen had the qualities of a Master, the temple treated him as a mere novice monk giving him only basic cleaning work to do. Yet again, C.T Shen stepped in and had him made Abbot. Gradually a few, then more Westerners began coming to the monastery. Although Sasaki Sokei-an had taught Zen, especially from the Platform Sutra, in New York in the 1930s, Shifu was the first Chan master to teach contemporary Chinese Chan to Westerners on the east coast of the US. The only other such teacher in the USA at that time was Master Hsuan Hua over in California.

Then he was called back to Taiwan. Master Dong-chu needed help in his monastery and it took time before the arrangement of alternating time in Taiwan with time in America became stabilised. When Shifu returned to the USA, he needed to live near the monastery and not with his sponsor much further away. He had then to finance his own life but having no money, he became a wanderer, sleeping on the streets, or 'nodding with the homeless through the night in coffee shops, foraging through dumpsters for fruit and vegetables.' For a man then in his fifties living this way in a New York winter was a hard life. Yet again, C.T. Shen assisted him finding places where Sheng Yen could teach and hold retreats. Shifu has always said that living in this way was a training invaluably testing his resolve, ingenuity and determination. In any case, as he pointed out, his life had always been like that and the self discipline imposed by Dong-chu's fierce training came to his aid.

Gradually a Chinese community with some Westerners formed around him and in time they bought a small building on Corona Avenue in Elmhurst in Queens. Although the present Meditation Centre on Corona is not in the same building, his presence in that area was established for many years. A pattern developed. Through his writings in Chinese and in English translation, he became known and through his personal charisma, Shifu grew into an influential figure in both Taiwan and New York. In Taiwan, he headed the Institute of Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture and also inherited Dong-chu's monastery outside the capital. Donations flowed in and, given the economic success of Taiwan, the sums contributed were large. Shifu was able to obtain a large mountainous estate on which, gradually, a magnificent monastery has been constructed. It is now an architectural showpiece and a functioning Chan Centre and monastery complete with a seminary developing full university status. In New York, he likewise obtained a large estate in the Catskill Hills thereby creating a beautiful meditation centre in the woods. It must be said, however, that Shifu's poor command of English and his long stays in Taiwan limited the success of his mission among Westerners in the USA.

It was during this period that I first went to New York to 'sit' in an intensive retreat with Shifu. He was very interested in my own work in Britain and in the little centre I had created in Wales. After I had attended several retreats, he came over to Wales in 1989 and led the first of four retreats in Britain. My work with him developed into a close understanding and Shifu made me the first of his Western Dharma heirs in 1993. I helped him lead retreats elsewhere, guestmastering for him in Berlin for example. But he was also developing retreats in Poland, Switzerland, Russia etc. This was a time therefore of increasing international involvement. As his name became known, he represented Chinese Buddhism at numerous conferences; in an important public dialogue with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, thereby healing a breach with Tibetan Buddhism that had lasted for centuries; and finally co-chaired conferences of world religious leaders under the auspices of the United Nations.

Chan Master Sheng Yen had become an international figure. In his addresses to conferences, his approach was always one of complete sanity, carefully attuned to the world situation and presenting the Dharma in ways his fellow religious leaders could understand and to a degree accept.

For me, writing this, what I recall are his more personal traits. On retreats, he could be a hard taskmaster but always understood the limits to which he could drive the participants. It became clear that this approach was deeply compassionate. As Master Dong-chu had taught him, confrontation with the ego is essential if wisdom is to sprout. In interview, Shifu could appear as a warm friend, as a critical schoolmaster, as a father, or present a remote even chilling distance after which one spent hours struggling to understand. Sometimes there was a depth present that left one groping to follow after him.

After his retreats in the UK, I was fortunate enough to be his guide for a few extra days. Once we drove through Wales to Hereford Cathedral, on through Oxford looking at the colleges and thence to London where we stayed in a 'pad' in Great Russell Street then occupied by my children in their late teens. Another time, I took him to see some of the amazing documents and paintings collected by Marc Aurel Stein in Dunhuang and Central Asia around 1900 and now kept in London. In Westminster Abbey, he bought the guidebook in Japanese. During these few days, Shifu was totally relaxed, a charming guest, a wonderfully insightful conversationalist and great fun to be with. At my children's pad, he noticed some unclean coffee cups hiding under a chair. He found this a great joke and humorously made good friends with my kids. In the museums, the bright ink of the ancient documents that often looked as if they had been written only yesterday delighted him. I was also able to drive him in terrible rainstorms up into the Pennine hills to visit Throssel Hole Abbey of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives. He spoke warmly with the monks and was very impressed by the life of this British monastery.

Shifu's death creates a tragic loss for all those who had the great good fortune to be taught by him but it is also an inspiration. His wisdom lives on in books, tapes, and video and in institutions. It is now the task of his Dharma descendants to take up the roles he has left for us to occupy.

1 Footprints in the Snow; the Autobiography of a Chinese Buddhist Monk. Doubleday 2008

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 2009. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q405