An Interview with Rebecca Li

We introduce Simon Child’s second dharma heir, Rebecca Li, interviewed by Skype from New York in January 2017. She edited the text and added some content that was not covered in the interview.

Was there religion in your childhood? Was there any sign of transcendence or vision? How about influences from Chinese culture?

I grew up in Hong Kong, which is a very Westernised place, and went to an English school, so I never searched for Buddhism. In fact, I almost became a Catholic in secondary school. The most memorable early experiences that might have primed me to be open to Buddhism were two. When I was about seven I was in my father’s hardware store in Hong Kong, and while alone I had the strong feeling that I was in the wrong place in the wrong body, like I didn’t belong there. It was a very strong and shocking feeling. “Why am I here?” I wondered. At that moment it felt like I belonged somewhere else. That memory and feeling stuck with me, and while I didn’t have any ideas beyond the feeling of awe at that strange feeling at the time, because it did stick with me so vividly I suspect it helped open me to the idea of past lives when I was eventually exposed to Buddhism. That said, I am not sure for one to practice Chan that it is necessary to believe in rebirth, but I definitely don’t close my mind to that possibility.

Later, when I was about eight, in Elementary School, I heard Hui Neng’s four-line verse (“There is no Bodhi-tree / Nor stand of a mirror bright / Since all is void / Where can the dust alight?”) on a TV show. I asked my mom, who was also watching, what it meant and she just said it was something Buddhist. I didn’t experience any realization or anything like that but I did find it intriguing, and thought that maybe Buddhism, whatever that was, would be interesting. My family was not religious nor was my mother Buddhist, but I did think at that time “If I ever have a religion it might be Buddhism.” So even though I never pursued it, or sought it out, that openness to Buddhism remained, so when I finally was exposed to it I had an open mind.

In addition to my family not being religious, we were also not brought up “traditionally”. The Confucian values of family, filial piety, duty and obedience are very strong for the Chinese. It is much more so in Taiwan and China than in Hong Kong, but it is still a common set of values in Hong Kong as well. However, my father was considered something of an eccentric because he taught us not to blindly respect someone just because s/he is an elder or an authority figure but we should think for ourselves whether that person’s views and actions are sensible, so I became very independent in judgement. This later affected how I related to Buddhism and Buddhist teachers. But more on that later.

How did you come to Chan? Tell me about your first meeting with Master Sheng Yen

It was not until I was a graduate student in California that I encountered Buddhism and began to feel its pull. I was going through a period of deep sadness after losing a friendship which had been very important to me at that time. A number of people treated me as someone who could help them with their problems, but in fact I had real problems of my own that I was not sure how deal with. I thought I must do something different, to try a new approach so I joined an Aikido class, feeling the need to connect my mind and body. It was an attempt to break my mode of living at that time which was very cerebral and focused on abstract ideas. I became interested in meditation after reading Eric Fromm’s Escape from Freedom in which he said reading, something I was doing a lot of, was a form of escape and perhaps we should try meditation. Even though I had no idea what meditation was, I was intrigued by the idea. I also met David at that time, now my husband, who was taking Qi Gong and Chan meditation classes.

David told me about the meditation classes he was attending with Gilbert Gutierrez, a student of Master Sheng Yen who later became one of Master Sheng Yen’s Dharma heirs. Hearing about that, I found myself reading a few of Master Sheng Yen’s books. They were a revelation to me. They explained so much, and many things started to make sense, in particular my friendship difficulty. It made sense that changes in causes and conditions lead to the coming into being and the passing away of impermanent feelings and connections, unfortunately even including friendship. But this helped me understand that what I was suffering over was a natural process, and that even though it was painful it was how things work.

My very first class with Gilbert Gutierrez was on Yogacara. I knew nothing at all about it conceptually, but did feel that it made sense somehow. One person in the class also reported on a seven-day retreat that he just attended with Master Sheng Yen in Queens, NY. For some reason that sounded like something I definitely wanted to do, and the sooner the better! In addition, Gilbert’s wife Ellen was Taiwanese and she had practiced for a long time, including under Master Sheng Yen. She had a lot of compassion and wisdom and influenced me deeply. One thing she told me at the time was, “Don’t go to any random teacher. You need to be careful who you follow. It is important to follow someone with clear lineage so that you will not be led astray.” Growing up in Hong Kong where we were taught to be sceptical about self-proclaimed masters of all kinds, such as those claiming the ability to turn copper into gold, I took her advice to heart. Based on what I read and his background, I felt that Master Sheng Yen would be a good teacher for me to follow. Years later when I worked on Shifu’s autobiography, I found that he practiced with new religious groups in Japan and it helped me become more open-minded about teachers from all backgrounds. As I met teachers from different traditions, it has become clear to me that it is an individual’s practice and conduct that makes one a worthwhile teacher. Around that time, Shifu (Master Sheng Yen) was due to make his first visit to California and I was absolutely sure I wanted to take refuge with him. As his visit approached I got very sick all of a sudden, and I remember this thought arising in my mind, “Maybe I will be too sick to travel to the refuge ceremony.” I was shocked to see that thought and said to myself, “Even if I have to crawl, I’ll go.” It was a taste of the practice of angry determination that Shifu would often talk about in retreat, and I knew that it was essential for keeping us on the path.

I have to say that I felt a strong connection to Master Sheng Yen from the beginning. I had not met him in person until that refuge ceremony and I did not know much about him other than a few of his books I have read (it was before the time of Google), yet I was sure that I wanted to follow him on my spiritual journey. Later on, I met many people who have studied with many different teachers in their search. For some reason, I felt that I had found my teacher when I met Shifu; there was no need to look anywhere else.

There are four lines that emphasize how rare it is to be born with a human body, what an opportunity it is, and how rare it is to meet the Buddhadharma and have access to liberation. These lines made a very deep impression on me. Master Sheng Yen started his journey along this line, feeling that Buddhadharma is so wonderful and it was such a pity that so few people knew about it. This was why he devoted his life to sharing the Dharma and I felt a similar calling to do so. Following Master Sheng Yen has thus always felt like accepting his invitation to everyone to join him to share the Dharma.

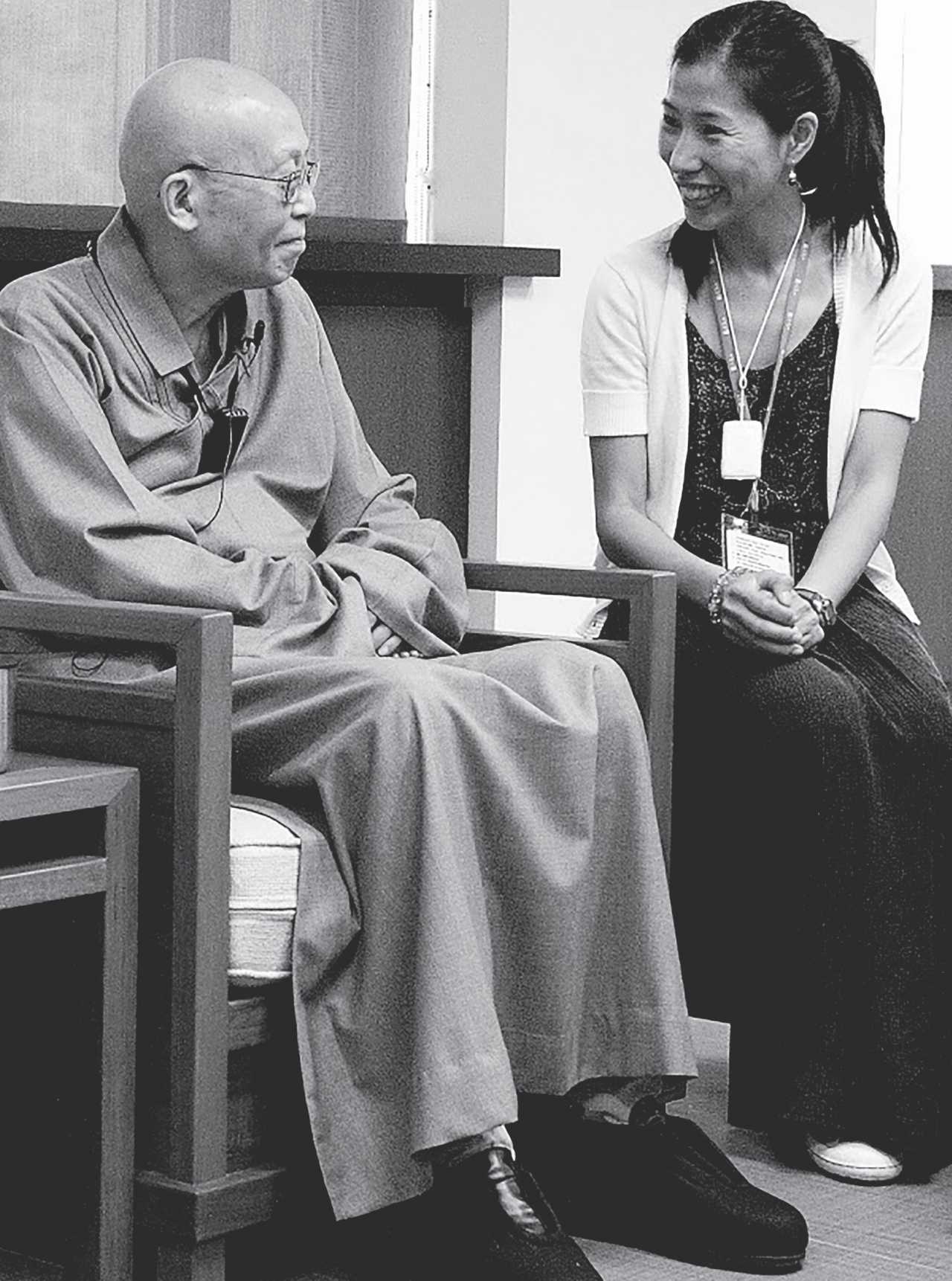

In the mid-1990s, Shifu’s intensive retreats were held in the Chan Meditation Center with enough space for only thirty participants. It was very difficult to get accepted to a retreat. I was so happy, after one failed attempt, to finally have the opportunity to attend a sevenday intensive retreat even though that involved flying across the country all by myself. In that retreat, like the next few, I was mostly dealing with drowsiness from jetlag and a drastically different daily schedule than my usual night owl life. When it was my turn for an interview with Shifu, I didn’t really have any questions for him. For some reason, I would just start crying as soon as I sat in front of him and could not stop. I remember feeling, “Thank goodness, I finally found you again!” Recalling this now still tears me up. It was as if I was with him a long time ago and got separated, like a child who got separated from her parents in a crowded market, and the joy I felt was like being reunited with my loved ones. At the end of my first retreat we had a sharing. Because my Mandarin was not good, I shared my experience in English. After I finished, Shifu looked me in the eyes and said, “You are going to help a lot of people.” It was a vivid memory because I was puzzled. I did not say anything extraordinary. I was barely able to stay awake during my meditation. “How on earth am I supposed to help a lot of people?” I thought to myself. Perhaps that comment helped put me on my path as I would use that to remind myself to make myself useful for others as I engage in the practice. It was that mentality that guided me as I served as Shifu’s interpreter, board member of Dharma Drum Retreat Center, Dharma teacher, and as a retreat leader.

How did you learn the specialist Buddhist vocabulary to translate for Master Sheng Yen? Please share some of your stories of traveling with him

I did not speak much Mandarin when I first met Shifu at the retreat in New York. I only had one course in college and my listening comprehension was still quite poor. I had to rely on Ming Yee’s translation to understand Shifu’s Dharma talks. When I was invited to be trained as Shifu’s translator I tried much harder to learn Mandarin. One difficulty was that he spoke with a strong accent which I could not follow at first. I learned to understand Shifu’s accent by listening to his recorded talks again and again, and listening to the translations of his previous translator (Ming Yee) to get to know the technical vocabulary. To learn the Buddhist terms I bought a Buddhist specialist dictionary and collected all kinds of glossaries that listed Buddhist terms in Chinese, Sanskrit and English and memorized them. As I gained more confidence in my translations, I moved away from trying to find the perfect translation for a specific term. I teach sociological theory which also has a lot of specialised language, and I have found it much more helpful when I explain these concepts to my students in layman’s terms and minimize the use of jargon. The goal is to understand the idea and the word used to communicate the idea is merely an approximation, so what is important is to work out what the idea really means. So I would ask Shifu to explain the concept to me and then construct my own English equivalent. I guess I did alright since from time to time Shifu would comment that the English explanation was clearer than the one in Chinese!

In this way I got to know Shifu well. We travelled together quite a bit, mostly for religious leaders’ meetings and also for a retreat in Switzerland. Since we shared hotel breakfasts together and worked together I had a different point of view from those who treated him as a god. I did not just see him as someone up on the stage or pedestal. I saw him as human, as a monk, and as a practitioner like the rest of us. Because my dad told me a person has to earn your respect I judged Shifu as I found him, not based on others’ notions, or mystical beliefs. Shifu most definitely earned my respect. He did so by being a serious practitioner, and by adhering to the Buddha’s teachings sincerely and treating each person with genuine respect.

Shifu had a very weak stomach, so he always travelled with an attendant who cooked his food for him and often with a secretary and other helpers as well. After 9/11 in New York he was invited with other religious leaders to the World Economic Forum, held in New York in 2002 to show solidarity (it is usually held in Davos, Switzerland). Entourages were severely restricted. Only a single translator was allowed, so I had to be his food attendant, secretary, liaison with Taiwan as well as translator, but he happily pitched in. So between us we did the faxing, secretarial work, reporting to Taiwan and so on. I did my best serving him food, knowing that I was probably breaking all kinds of protocols as attendant since I did not really know what they were. It was totally not a problem for him that things were not done the usual proper way or in the correct sequence. And he was willing to chip in and do whatever needed to be done. He was capable of not being the VIP, and did not have a self-important ego.

When I had the responsibility for running the retreat centre in upstate New York he was able to play the role of President without always being in charge. If people tried to lobby him for changes at the retreat center, he would refer them to me. He did not have to exercise his power. When I read about abuses of power in some other Zen communities Shifu’s example stuck with me. It is important for the teacher to be aware that just because others let you be the power, you do not have to.

When we were working on his autobiographical book Footprints in the Snow he used to completely forget about his Master’s “dignity” and he would act out scenes from his childhood and youth to me. I remember him down on the floor demonstrating the push-ups he did in army training, a wonderfully informal man reliving it all for the book.

On a trip to Jerusalem for another meeting of religious leaders I saw how quickly he absorbed large quantities of information and could understand why he was so successful. I gave him a briefing, using the information I read, on the history of various sites we visited and the city itself. A film crew from Taiwan was traveling with us for a documentary of Shifu. When I saw Shifu’s interview on this trip, he repeated everything I told him about the history of the sites. It was really impressive what a fast learner he was, especially when he did this amidst a busy meeting schedule for the religious leaders. Also on that trip I saw him forego his special meal, out of a delicate concern for others who could not eat at the same time, knowing that he would suffer for it later. To this day, I still draw on things I learned by watching Shifu’s responses to situations during our travels when I try to figure out how to handle difficult situations I encounter.

Could you share with me some of your retreat experiences?

When I started attending retreats with Shifu, they were not divided between huatou and Silent Illumination. I mainly learned how to use the breath method and it seemed some participants were practicing with a huatou. Those were very important retreats as they laid the foundation of establishing right views and proper attitudes toward the practice for me.

In my early years serving as Shifu’s translator on retreats, I attended several huatou retreats mostly because they were the ones that fit into my schedule. I was a slow learner and it took me a while to appreciate how powerful huatou practice was. Then in 2004 when I travelled with Shifu to Switzerland to translate for him at the Silent Illumination retreat I told Shifu that the huatou still came up on its own. He said, “That’s okay. In the depths of silence there’s the question anyway.” It helped me understand that the separation of the two styles is somewhat arbitrary. They are different doors to enter the same room.

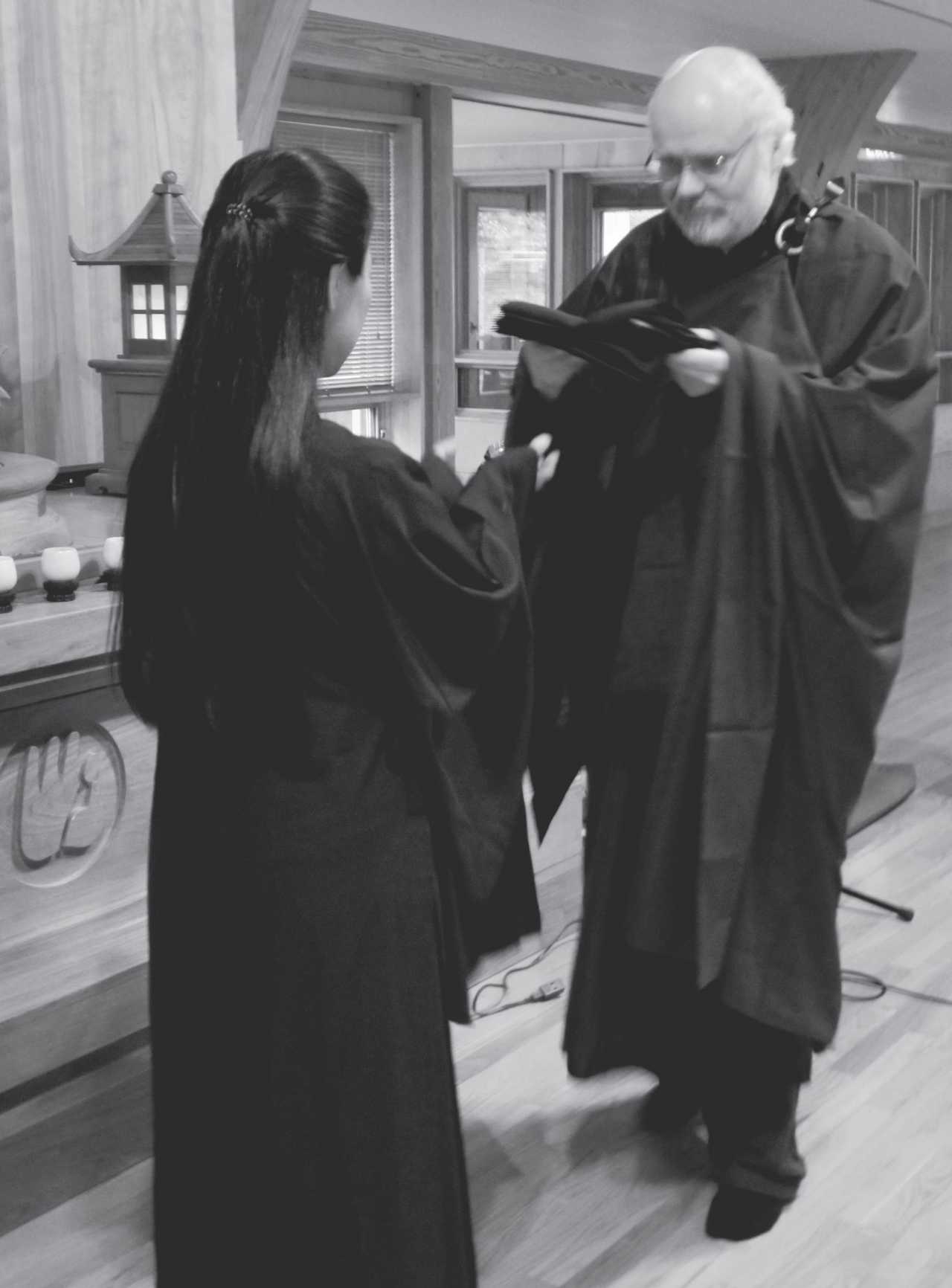

My first Western Zen Retreat with John Crook in 2001, however, transformed my practice. The combination of communication exercises and intensely personal interviews pushed me deeper into my practice. Because of that, I consider John my second teacher besides Shifu. I believe his approach is an important innovation in Chan to meet the needs of practitioners living in the modern era. I was able to see through many of my vexations in the retreats with John, which were often co-led by Simon Child and Hilary Richards. After Shifu stopped travelling to the U.S. for retreats, John and Simon became my main teachers. Besides participating in their retreats, I began my training with them first as guest master and then with Simon to conduct retreat interviews. I started training exclusively with Simon after John passed away in 2011. The training was a very important part of my practice in those years. They helped me work through a lot of deeply entrenched habitual tendencies. Learning how to conduct retreat interviews and lead the Western Zen Retreat was one of the most difficult things I have undertaken. I wondered many times if I could ever get it. Learning how to persevere through it all was one of the many great gifts I received from Simon for which I am forever grateful. In a retreat I sat with Simon in 2010, causes and conditions came together and Simon informed me that I had seen the nature and I wrote about it in a retreat report. I can’t help but feel that I am the most fortunate person on earth. Meeting and practicing with a great master like Master Sheng Yen is already a great blessing. I was also able to meet and study with two other great masters, John Crook and Simon Child, along with others who have taught me on the Path. The only way I know to repay their kindness is to share the Dharma using what I have learned from them.

Now that you have received Dharma transmission, what do you want to do with it? Will you lead retreats in Britain? Will you start your own Sangha? Will you teach in a traditional Chinese or modern Westernized style, or reform the teaching in some way?

As you can see, I came to Chan like many westerners or “convert Buddhists” did. The way Shifu taught in the West appealed to those of us with more scientific minds like John Crook, Simon Child and myself, people who are not prone to swallow beliefs based simply on authority. John adapted the teaching to incorporate a learning style more common among the western-educated. This is the style I can relate to the most and I find helpful to practitioners in my retreats and classes. As for whether I will lead retreats in Britain, we will see how causes and conditions unfold. Fiona Nuttall is my dear Dharma sister and I will support her in whatever way she needs me. I co-led a Western Zen Retreat with Hilary Richards in 2015 at Maenllwyd and had a wonderful experience. It was a lot of fun and we received a lot of retreat reports from the retreatants. I think they could sense the joy Hilary and I were feeling as we shared the space. I have made many friends with the Western Chan Fellowship sangha over the years and would cherish the opportunity to practice with them again, on whichever side of the pond that may be.

As a Dharma heir my most important responsibility is to carry on the lineage and identify someone with the Great Vow to commit to carrying it on as well, while continuing my practice and teaching. It has struck me how much there is to do. Besides my full-time job as a sociology professor, balancing my responsibilities for Dharma teaching, retreat center business, family and civic life will be a lifelong practice. As for any specific plan, I have not yet made any major decisions yet. I have been doing a lot of thinking, considering my abilities and limitations as well as feeling out the shifting causes and conditions. I am giving it some space to allow things to take shape. I have been thinking a lot about teacher training, knowing full well how long it took to train me when I had such dedicated teachers. I still remember how many people started when Shifu began training us to be Dharma Lecturers in 1999 and how few finished the training, and fewer yet stayed on as teachers. It reminds me again of the importance of Great Vow, as Shifu often emphasized. So I have also been thinking, “What can I do to instil that Vow in students?”

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2017 Other Articles Rebecca Li

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-470