False and True Self

Reprinted with permission from Chan Newsletter, 69, 1988 and lightly edited. Based on a talk given on JHC's first visit to Shifu.

Ananda asks the Buddha about the nature of the self. Is there an all-encompassing ego, a true self that unites everyone in the world, or is there a self at all? I'm going to talk about this question and discuss how it is dealt with by "outer path" systems of thought and religion and how it is dealt with by Buddhism. Schools of philosophy and religion other than Buddhism are categorised as "outer path" because the adherents to these views attempt to look outside the mind for solutions to the problems of the world.

When we use the words "outer path" there is no connotation that such views are bad or heterodox. The idea of outer path simply signifies the idea of looking outside to resolve problems; not looking inward.

In a retreat that ended here at the Centre recently there was a psychologist from England who told me that he heard things at the retreat that he had never heard before and he believes that this knowledge will be of great use to him. I asked him, "What did you learn?" "Four lines in the evening service," he said, "really impressed me: 'To know all Buddhas of the past present and future, know that Dharmadhatu nature is all created by the mind.'" I asked, "How do they help you?" And he said, "For example, if your legs hurt you need not be afraid of the pain. You can concentrate on it and it will eventually turn to coolness. Pain is created by the mind, so if can be ended by the mind."

The psychologist told me that what Western psychologists usually do to help patients is either to use talk therapy or administer drugs. But he had never before understood that to accept pain is a way to resolve it. So I asked him if he thought this method would apply to everyone. " Probably not" he replied, "it would only be useful to a strong-willed, goal-oriented person. Otherwise I doubt that the method would be useful."

This method may not be applicable to everybody, but the principle behind it is valid. This is to say that problems must be seen as existing in the mind. Certainly if you get a flat tyre or you are wounded then that is a problem, an unforeseen occurrence which must be taken care of. But usually the reality of what must be done is nothing compared to the way such occurrences are seen and exaggerated by our minds.

There are so many things we normally perceive as problems which have no basis in reality, which are entirely created by our minds. To someone whose mind is clear, an event which might strike another person as an "objective" problem will have no existence at all. Buddhadharma considers other philosophical and religious approaches to be "outer paths" for the following reason: these schools of thought perceive a variety of things or phenomena as problems and they see the origin of these problems in a variety of conceptual factors that lie outside the true domains of the mind. Thus they will attribute the cause of a given problem to any number of factors: physical, psychological, social, familial and so on. such perceptions are not accurate. In the view of Buddhadharma, all such problems and their causes exist within the mind.

Outer path views which seek solutions outside of the mind have an understanding of the self that is different from that of Buddhadharma. Some view the true self as something internal, a sort of primary essence. Others see it as something external like a great oversoul that unites everyone and transcends the personal self. People who hold this view consider the true self to be something that pervades the ten directions. To look for the answer outside the mind in this manner is to be on an outer path.

There's a joke that shows how people live inside their narrow views. Note that in China surgeons are called "external doctors," since they approach the body from the outside. Others who treat disorders with medicine are called "internal doctors." The story is this: a surgeon, an external doctor, visits a patient sent to a hospital with flu. The doctor takes one look at him, cuts him open, finds nothing amiss and leaves, saying, "I've done all I can. It looks like you need an internal doctor." The internal doctor arrives and asks, "Do you feel any pain?" The patient says, "You bet, the pain is killing me." The internal doctor finds the patient's reaction to a mild case of flu to be bizarre. He tells the patient, "You're suffering from delusions. I'm going to recommend a psychiatrist." The psychiatrist enters and asks, "What do you feel?" The patient answers, "Pain, a lot of pain, right here where the surgeon opened me up." The psychiatrist says, "That's not my turf. You'd better call back that external doctor."

What is the problem here? Each doctor treats the patient according to his own speciality. No one tries to understand the problem in its totality. Each acts according to what he knows, not what troubles the patient.

Let me return to the concept of true self. It is not something generally understood by ordinary people who tend to know only their personal selves and what they can see, hear, taste, touch and smell. This is really a very limited domain. What is beyond this realm of the individual and the senses? Is there a self beyond what we know, beyond what we can perceive?

It may seem that there is a true self which can reach through all space and time. Certainly ordinary people do not have the vaguest notion of the concept of such a true self. Only people who have practised hard or read and thought deeply in philosophy arrive at such an understanding. A religious practitioner may be able to experience a higher plane of existence outside of himself. A person with deep philosophical understanding can deduce a self beyond himself. Only such people as these can try to come to an understanding of a true self.

The other day I read about a man who received an artificial heart. He found out after the operation that the heart was not mechanical but was that of an animal. He may have thought, "What am I really, an animal or a human being?" He also lost a lot of blood and had several transfusions. Most of his blood was other people's. So he might have thought, "Who am I now?"

What do you think, is he his original self or not? Maybe there will come a day when even brain tissue can be replaced. Who knows? We might be able to become smarter. Or perhaps someone in an accident might suffer brain damage and his brain will be replaced by a computer chip. Who would he be then? People will have to reflect on questions such as these. Usually, when you refer to a true self, ordinary people will point to themselves and say, "This is my true self. No doubt about it. Every part of what you see is me." But then when parts of the body start to get replaced people may begin to wonder.

When I first met westerners I was a child in China. There was something about the way they smelled that I had never experienced before. Later I understood that it was a question of diet. I, and those around me, had not grown up on a diet of meat and milk. That's why I thought some of these westerners smelled like cattle. But now I also drink milk, and I'm around many other people with a similar diet. I don't sense anything different now. Who knows? Maybe I have the same kind of smell as the first westerners I first met.

Your body was given to you by your parents. First you were a baby; now you're grown. During these years you may have eaten all manner of different things: beef, pork, chicken, milk, cheese. You used the nutrients from these sources to build your body but you do not doubt what you are. You are a human being even though parts of many animals have been introduced into your system and worked to transform your body.

Milarepa, the great Tibetan master, lived in the mountains in a place where there was nothing to eat but wild grass. As a result his body turned green. I lived in the mountains also, and for a few years I ate nothing but potato leaves. People asked me why I didn't turn green. It was because I cooked the leaves first.

A lot of people assume that their body is their self. This cannot be. Before you were born you did not exist in your body. After you die the body cannot accompany you. In what sense therefore do you really exist?

Questions such as these cause us to distinguish between a self, meaning the self you can see and feel at the present moment, and a true self. Do you believe that there is an existence before birth and death? Why do you believe what you do?

A Christian asked me what my views of heaven and hell were. That brings us back to the beginning of this discussion when I said that everything is created by the mind. You have your heaven and I have mine. You have your hell and I have mine. You may see me in your heaven and I may see you in mine. Nevertheless, they're not the same. We're all here in America but I have come from China. The America I see is different from the America you see. Even a couple who share the same bed really share two different beds. And the world we live in? Are we in the same world?

Some of you seem to think that we all live in the same physical world, that we all see the same rain outside. Actually the rain that falls on you will not fall on me. Hence what you feel and see is not what I feel and see. Perhaps the simplest example of that is a chair. If I sit here you have to sit somewhere else. And, of course, the seats we sit on are different to begin with.

Only advanced practitioners, through much hard work and practice can live in the same world. They must achieve the exact same mind. If your mind is scattered you can't live in or experience the same world as another person.

Up until now I haven't really spoken about the true self. What most of us believe to be the self is an emotional self, so to speak. This is the self that we know when we are under the influence of emotions, feelings and moods. This is not the self that wisdom can see. Only someone no longer troubled by his emotions can seriously try to know his true self.

Some people come along to the Centre hoping to find enlightenment immediately. They hope I will provide a wonderful method to lead them to liberation but I never do this. What I do is to first give a method that can be used to quiet the emotions. When there is some relief I may then give a method to seek the true self. I might give the huatou, "Who am I?" or "What is wu?"

Although I give methods to seek the true self this does not mean that Buddhadharma accepts the doctrine or the existence of a true self. Of course, this search for the self is central to many outer path beliefs. In Chan this search is also a necessary step. This does not mean that there is in fact a true self to be found. Many methods of Chan practice are devoted to the discovery of the true self.

If you ask an ordinary person about his conception of the Buddha he might come up with something like: the Buddha is what is unchanging, all-pervasive, and most perfect, the ultimate true existence. The purpose of Chan practice is not to discover the Buddha. In the course of practice you may try to use your power of reason and your understanding of Buddhism. To the question, "What is Buddha," you might answer that he is the awakened one, or the most perfect one. Such answers are wrong.

All such answers - that Buddha pervades through all time and space, that Buddha is that which never changes, the eternal and the unmoving - are wrong. The opposing viewpoints - that Buddha is not space or time or is outside all concepts - are equally wrong. You must try not to cling to either extreme and to let go of the centre, as well: this is madhyamika, the middle way. Could this be the way to find true self?

If you continue to hold on to a concept such as true self, or an idea of something that pervades through all space and time, then you are holding on to an attachment: an attachment to an idea predicated upon or imputed to an object. The object remains no more than such as it is.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

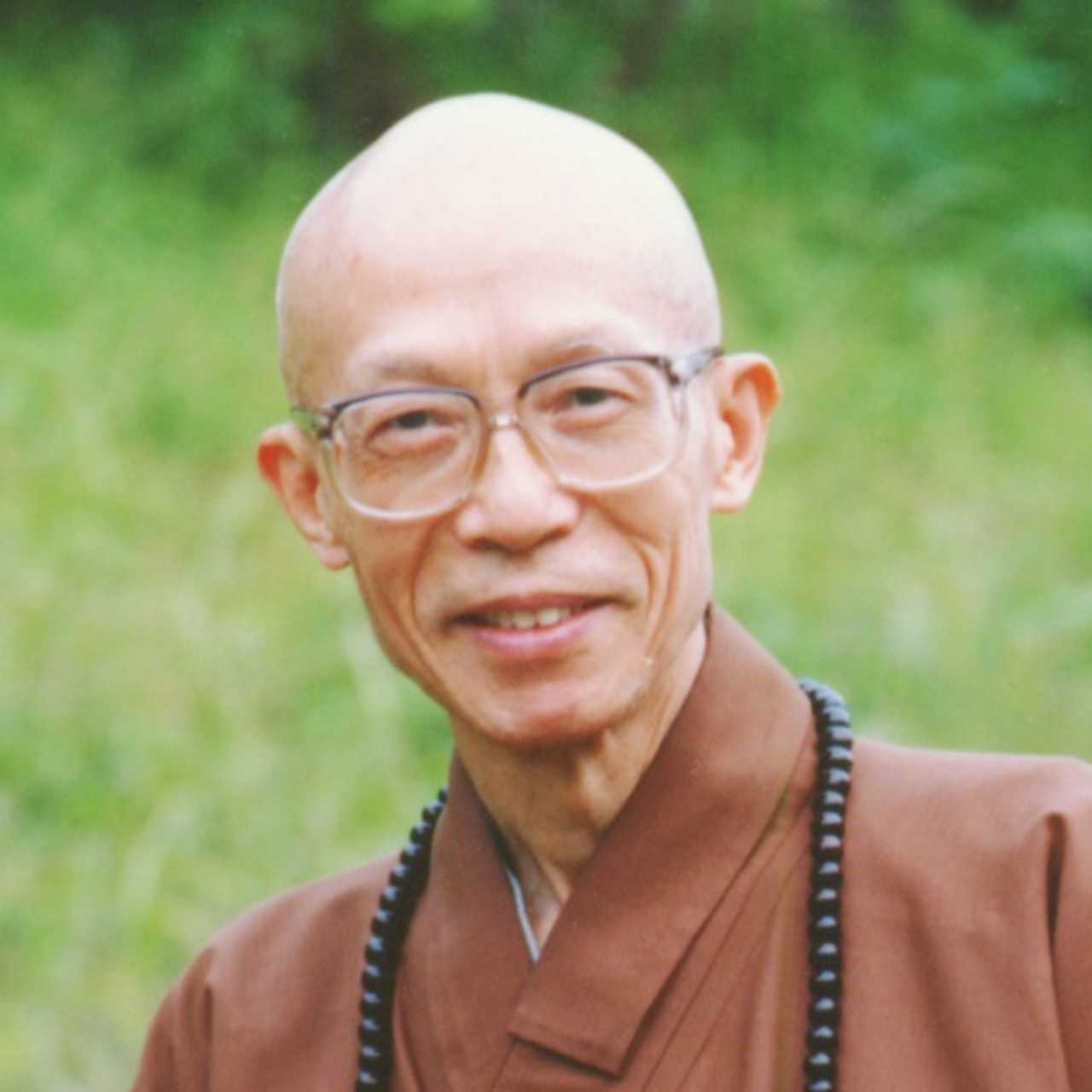

- Categories: 1987 Dharma Talks Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-117