Human Conciousness in the Chan Perspective

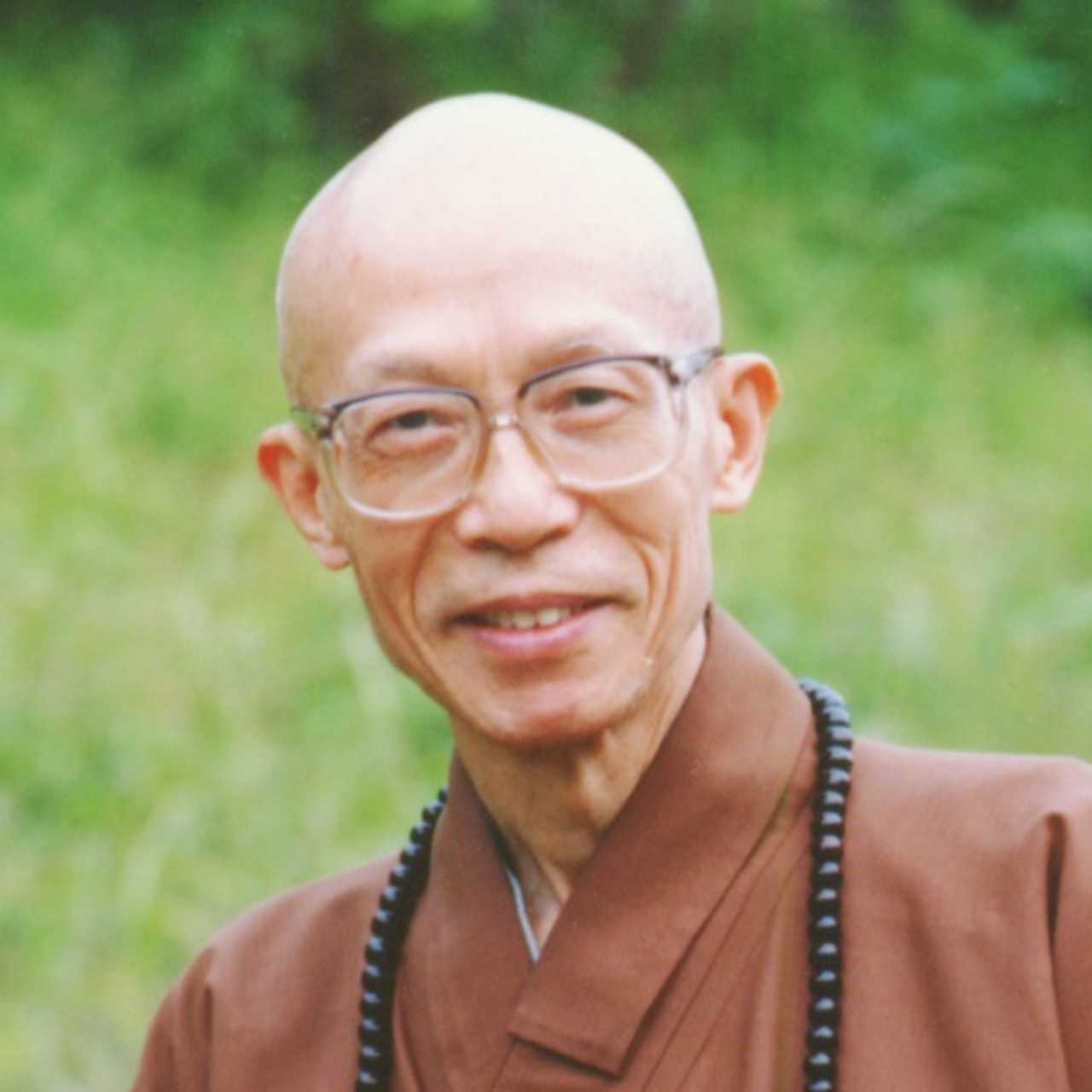

Chan Master Sheng Yen

Edited version of a lecture delivered by Master Sheng-yen at Brooklyn College on November 8, 1990. From Chan Newsletter No. 84, March 1991, with permission.

Buddhism generally divides human consciousness into False Mind and True Mind. False Mind, sometimes called the illusory mind, refers to the mental activity of ordinary sentient beings. This mind is filled with innumerable vexations that arise from a self centred view of the world. True Mind refers to the mind of wisdom, a mind free of vexation. Buddhism understands that False Mind includes all levels of human consciousness and activities associated with it.

What distinguishes the True Mind? True Mind arises only when mental activity is free from self-centredness. At this point consciousness is no longer subjective and self-concerned. Only perfect, completely objective activity remains.

The Chan Point of View

Don't get the idea that Chan is something different from Buddhism. It is simply a part of Buddhism and its understanding and perspective fall within Buddhism's basic tenets.

In Chan we speak of a Buddha Mind, which is the same as the True Mind referred to earlier, that is, the mind of wisdom. We also speak of the mind of sentient beings, which is the same as the False Mind of vexation.

One important function of Chan is "to illuminate the mind and perceive Buddha nature." Why does the mind need illumination? It is because the mind of sentient beings is clouded in darkness, and this darkness must be lifted if you are to see the true nature of reality. The term "to illuminate the mind and perceive Buddha nature" means leaving the mind of vexation behind in order to attain such wisdom. The goal of Chan practice is no different than that of Buddhism.

The goal is the same, but the words used are often different. Chan does not usually use terms such as "idea" or "discriminating consciousness." Chan simply uses the word "mind." Only those well versed in the tradition can read the writings of the Chan master and tell whether "mind" refers to the Buddha Mind or to that of an ordinary sentient being.

Chan practice revolves around this idea of mind. For the beginning practitioner, the foundation of practice and the path of practice are none other than the mind of vexation - False Mind. But the goal of practice is the Buddha's wisdom, the True Mind. There are times when the word "consciousness", as understood in the West, can be used to represent the word "mind" as it is used in Chan. However, the word "consciousness" cannot cover all the meanings of "mind" used in the Chan tradition.

In the West mental activities are researched, analyzed and recorded. But can the state of True Mind, the mind of wisdom, be considered a mental activity?

If we attempt to use "consciousness" to explain True Mind, there will be confusion. It might be possible to say that the True Mind represents a kind of pure, undefiled mental activity whereas False Mind represents impure mental activity, but this would still be inaccurate. Chan simply uses mind and avoids confusion.

This is because in Chan practice, we can see that both the Buddha Mind, and the sentient being mind are not separate from one another; we look upon the Buddha Mind as the goal of practice and the sentient being mind as the process of practice.

When you first start to practice, it is likely that you will notice that your mind is not at ease, not calm and peaceful. You use a method to change that. Such a method of practice is called "calming the mind" or "stilling the mind." This process can also be thought of as "clarifying and settling the mind." One can use the analogy of a glass of muddy water that becomes clear once the water is still and the mud has sunk to the bottom.

The Chan Approach to the Problems that Arise from Human Consciousness

What is a "beginners mind?" This is the mind of an ordinary sentient being who takes the first step in turning his or her mind toward illumination. He has a first glimpse of the meaning of Chan. This step is sometimes called "the initial generation of the Bodhi mind." What is Bodhi? Bodhi is a Sanskrit term which can be translated as awakening or realisation.

The Chan approach toward resolving one's problems is quite different from the methods used in the West. In the West, a person's problems are the centrepiece of the analysis. They are analyzed, themes and motifs are suggested, and the patient is urged to recognise patterns that have developed from early childhood and break the hold they have on him.

The approach of Chan is different. When a practitioner feels a need to deal with his own problems, he is urged to simply put them down and leave them behind. This does not mean that you should ignore what you do. It simply means that you should abandon the idea that what confronts you constitutes a "problem." You continue to deal with situations, but you no longer see them as problems. In this way the problems cease to exist.

How do you go about putting aside your problems? The solution arises when you develop compassion for other human beings. When you see the vexation and suffering that torments others, you can try and help them resolve their problems and end their suffering. You forget your own problems.

Where does compassion come from? Compassion comes from the Bodhi mind, the mind of realization. As you develop this mind, you begin to engage in activities that are no longer self- centred. You begin to deal with all problems in an objective way. Ironically, it is in this way that you will resolve your own problems. With this attitude, you clear away the mind of vexation and attain the mind of wisdom.

Last week I travelled to the West Coast of the USA where I gave a talk in a hospital. The audience included psychiatrists and other neuro-scientists. At the end of my talk they asked me the following question: "You say that your methods are simpler than ours. How can that be?"

I said, "When you deal with patients, you have to find out a great deal about their personal history. You must ask a great many questions. They often must come back again and again and this process can last for years. When I address someone's problems I don't spend too much time finding out about their background. I say one or two sentences, and that will begin to provide them with help."

I added that among my students, or patients if you prefer, there are a number of psychologists and psychiatrists. Some come to me because they have developed problems after listening to so many of their patient's problems! Others come for no reason other than to learn the way of Chan practice so that they can help themselves or their patients.

When one is first exposed to Chan, it may not be very easy to use Chan methods in conjunction with psychotherapy. The basic conceptions are quite different. Generally speaking, the Western approach is more analytical and the Chan approach is more immediate. It is also important to add that unless the Chan master is outstanding, it will be difficult for him to be effective in helping people. By contrast, some types of Western therapy can be learned in a reasonable amount of time, so that the therapist can provide his or her patients with some relief. But in the beginning, it is not easy to combine the two approaches.

Let us now look at the Chan method and the way in which it can help people deal with psychological problems. Chan recognizes that suffering, vexation and confusion are created within the mind, not from some external, physical world. This is the state of consciousness that Chan methods address.

Methods of cultivation fall into two general categories. The first is called, "contemplating the mind"; the second, "transcending one's thoughts". The methods in each category serve a special purpose. Which category is best depends on the person. And it may happen that one person can employ methods in both categories.

The general procedure in contemplating the mind is this: you keep your attention on the present moment and focus on some external object, a feeling or part of the body, or simply a thought or an idea. If you are concentrating on a thought, this can me described as using a later thought to observe an earlier one. This method helps to overcome the mind's disorganization when your thoughts come and go in a disorderly and random manner. This method will help you stabilise your mind. Gradually thoughts will become simpler and less chaotic.

There are many specific methods of contemplating the mind. For example, you can concentrate on the up and down movement of your lower abdomen while you breathe, or you can concentrate on the inhalation and exhalation of your breathing. Or, as mentioned earlier, you can watch your thoughts as they arise and disappear. Or you can try and keep your mind in a state free of thoughts. With this method, if any thoughts arise, you ignore them and try to bring your mind back to the thought- free-state.

These methods may seem simple, but they are not easy to do. They take a lot of practice. We have an eight hour class at our Centre just to teach the very simple method of counting the breaths. This is because there are many subtle aspects to this method. Improperly understood and executed, the method will leave your mind running wild no matter how hard you try to contain it.

Transcending your thoughts, the second category, is a method that consists of maintaining the attitude of non-involvement with yourself or others. The goal of this method is roughly described by a Chan phrase that translates as, "Be separate, or free, from the mind, from thoughts, and from consciousness." To be free from all of this is to be in a state of enlightenment. In such freedom of mind it might be said that we see the world.

No matter what method you choose, you must remember that when we practice in the Chan tradition, we refrain from using words or speech. Why is this? It is because words represent ideas, concepts, mental descriptions. And it is only by leaving these behind that we begin to understand the True Mind. Two Chan maxims convey this idea. First, "Any thought is wrong." In other words whatever you are thinking is erroneous, no matter how clear or accurate you believe it to be. And second, "Whatever you say is wrong." No matter how well chosen or clearly spoken, your words rely on thoughts and ideas, and thus, they are fundamentally wrong.

Nonetheless, you will notice that Chan masters talk a lot. They sometimes write a lot too. But the import of what we talk or write about is to convey that whatever you think or say is wrong. That is the content of all my talks. No words or description will suffice to describe a state of realization. Anyone who attempted to describe such a state would be considered by a Chan master to be a smart devil, not an awakened being.

Therefore, many Chan masters use no words when they interact with their disciples. They use movements or gestures. Or sometimes when they do use words it is in an unconventional way. If a student asks a question about A, the master may give an answer that refers to B, something totally unrelated.

These methods are designed to help students drop the habit of trying to reason themselves into True Mind. Reasoning will not free you from mind, thought, or consciousness.

The story from the T'ang dynasty tells of a disciple who asked this question of his Dharma Master: "How can I calm my mind?" The master said, "I am too busy to talk to you right now. Why not consult your First Dharma Brother?" He did as he was told and asked the same question. The First Dharma Brother said, "I have a headache. I can't talk now. Why not talk to Second Dharma Brother?" But the Second Dharma Brother said, "I have a stomach ache, why don't you just go and talk to our Dharma Master?" So he went back to his master and complained, "Nobody told me anything. Nobody gave me any answers." But the master said to him reprovingly, "You really are a stupid fool. Everybody has been giving you the answer." Because of this, the disciple reached enlightenment.

Does this make sense to you? If you have any questions, I'll just refer you to some professor here. Maybe he can tell you what you would like to know.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 1990 Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-107