Introduction to Meditation

An introduction for those new to meditation and for those who wish to develop their meditation further.

What is Meditation?

We are used to the concepts of training the body in a skill or for fitness or dexterity, and of training the mind in factual knowledge or in a mental skill such as arithmetic. Meditation is many things but it is none of these. Meditation is a training of the mind to be calmer, clearer, more attentive and concentrated. Meditation is also a tool for investigation into the phenomenon of mind, making use of calm clear awareness to directly experience the basis of mind which ordinarily is obscured by busy thoughts and memories. Though primarily a mental practice, meditation is inseparable from bodily experience which provides a focus for stabilising and awakening the mind, and which is the source of the sensory experiences from which we create our mental world.

Meditation is an ancient practice known to humanity for thousands of years, coming down to us in many forms through various traditions. Buddhists have practised these meditation methods extensively, classifying and refining them, understanding the differences between them and how best to apply them.

For beginners to meditation

For most beginners to meditation the important first step is to learn how to calm and concentrate the mind. There are specific meditation methods to assist with this. Most of us juggle many responsibilities and concerns and have busy distracted minds. Even when we are in-between activities our mind is never at rest – we are ruminating on what has happened in the past, or speculating on what may happen in the future.

Once we have made some progress in calming the mind we may be able to take up the other principal aspect of meditation, using methods which cultivate awareness and which give us insight into the basis of mind. We discover where our thoughts come from, how they proliferate, and how they may take us in the wrong direction. Such insight enables us to free ourselves from long-established but often unhelpful habits of thought and action.

Setting up an environment for meditation

An experienced meditator can meditate in any situation. For the beginner it is much easier to do so in a quiet place, so try to find a quiet location where you are unlikely be disturbed. Making use of a spare or unoccupied bedroom can be suitable. Turn off your mobile and set the answer-machine on your landline. If there are others in the house explain to them that you don’t want to be disturbed for a little while unless it is a real emergency. You will need an upright chair or alternatively a kneeling bench or firm meditation cushion (zafu) with a mat or blanket.

Joining a meditation group will be supportive. The group will have found a suitable location, and meditating with others offers a shared schedule and discipline to support your resolve to persist in meditation.

Caring for the body during meditation

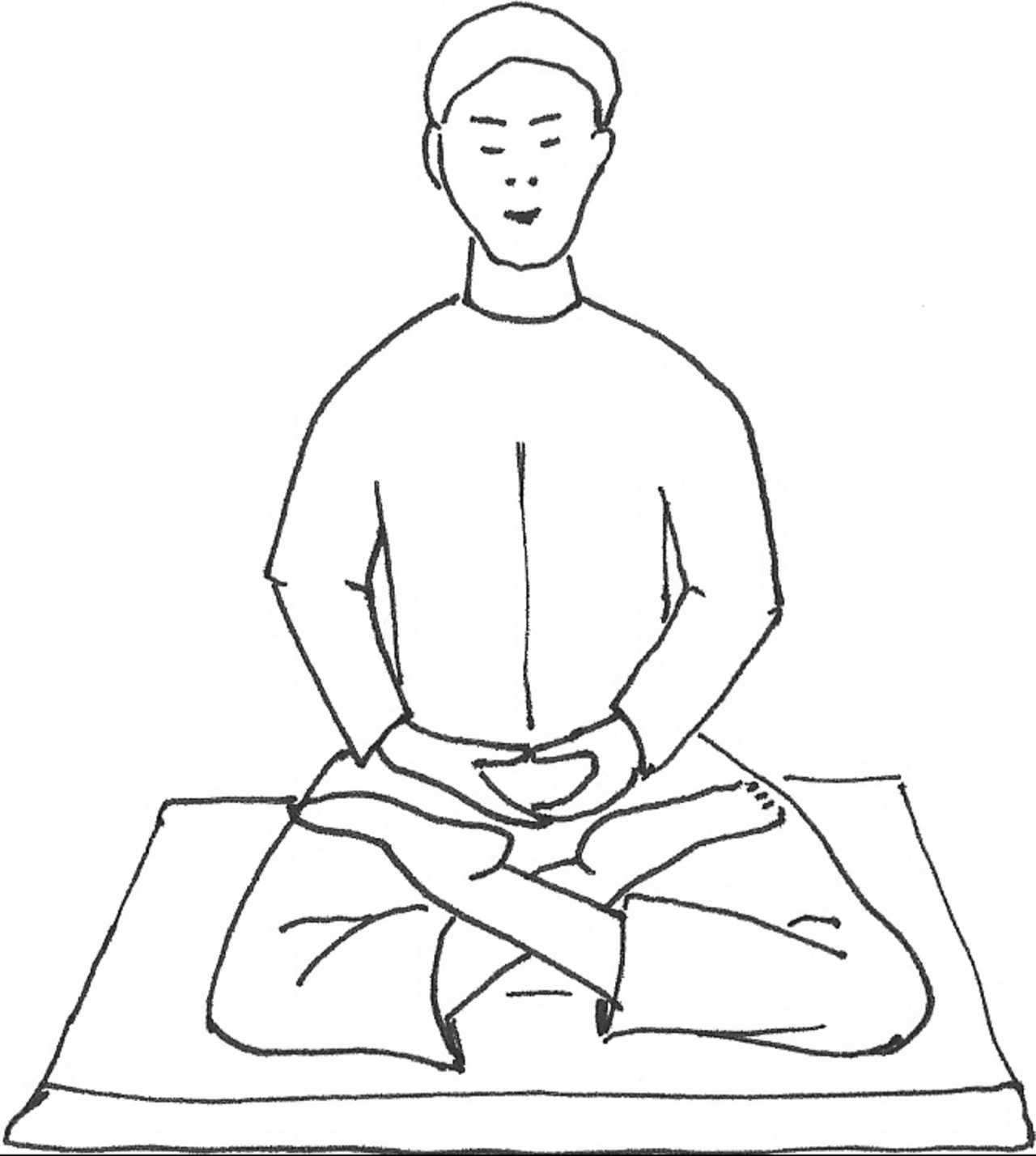

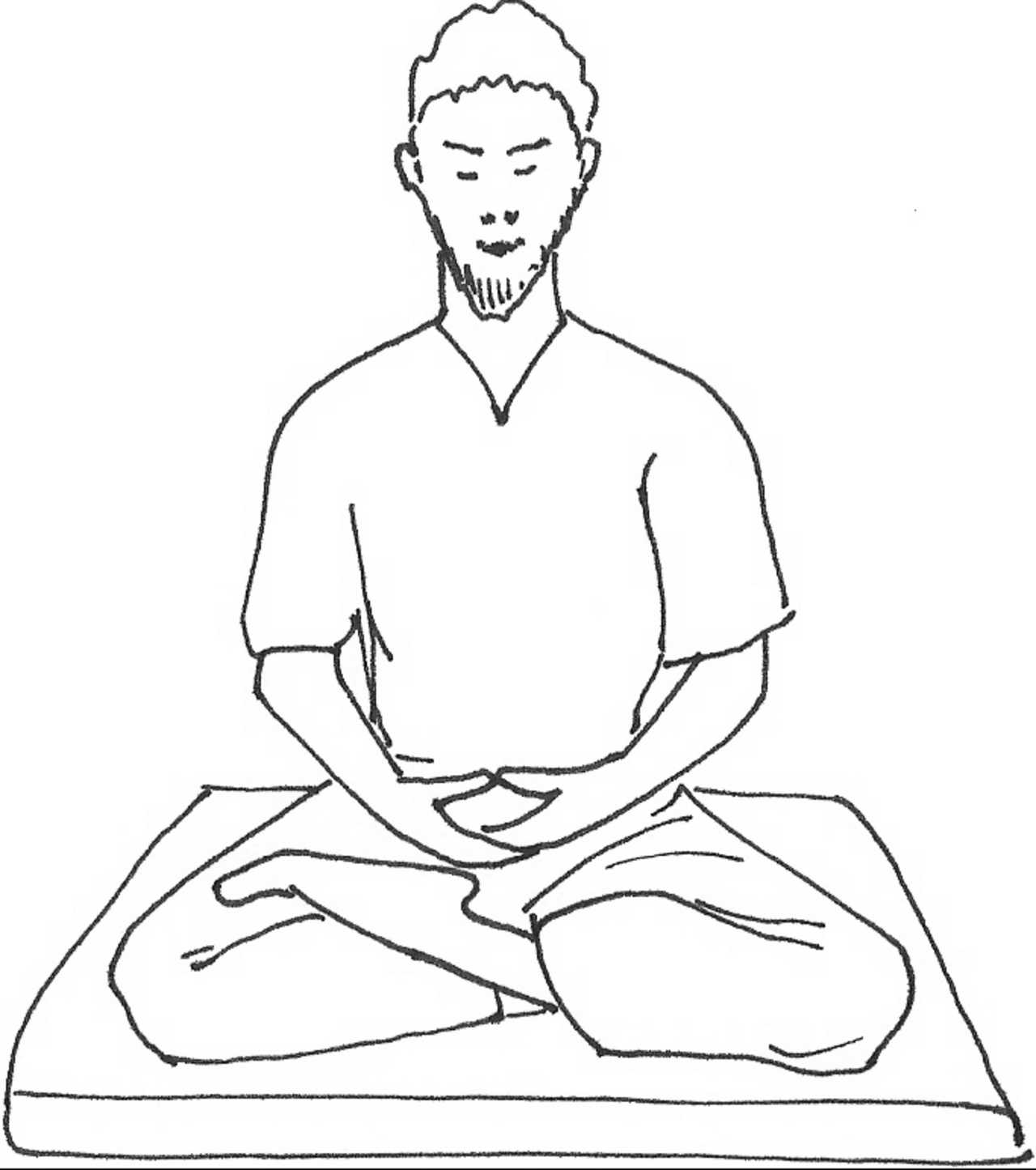

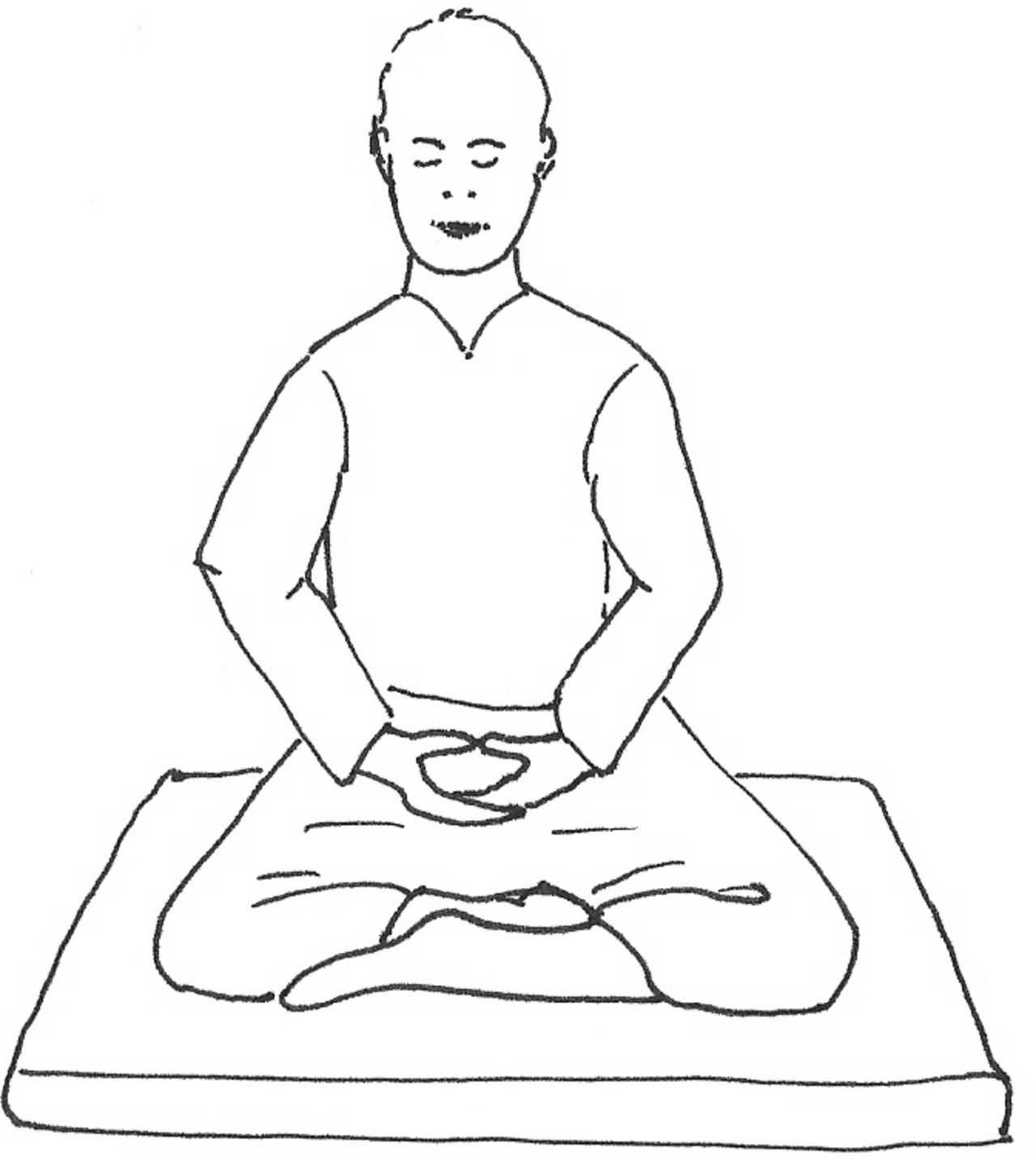

Meditation is usually done in some variant of a seated posture and for this reason meditation is often referred to as ‘sitting’. There are several postures which may be suitable. The key is to identify a meditation posture in which you can remain balanced, stable, and relaxed, so that your mind is not disturbed by an uncomfortable body.

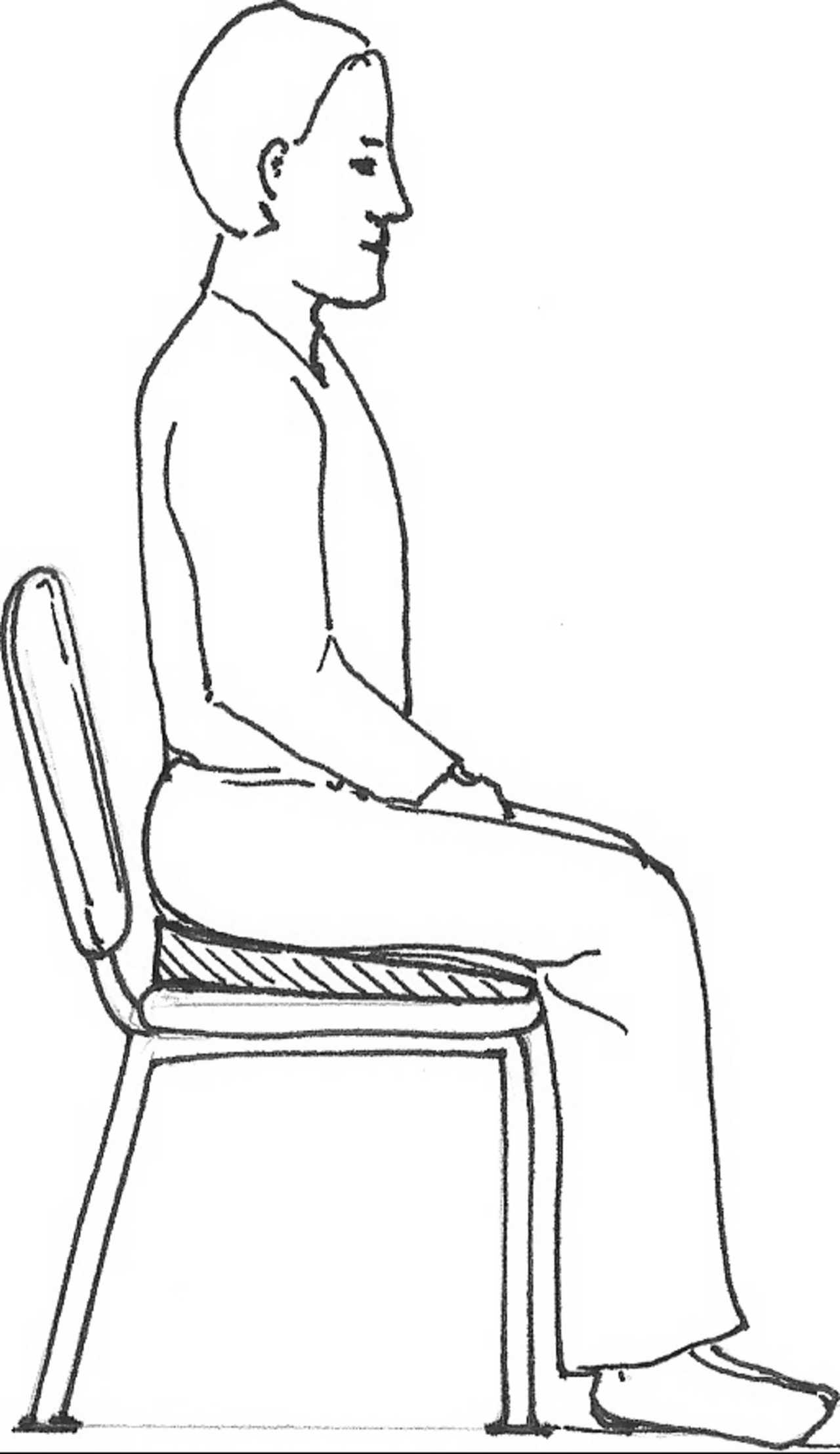

Sitting on a chair, preferably an upright dining-style chair, can work well. Use a wedged cushion or sit on the front edge of a meditation cushion placed on the seat, without leaning on the chair back.

Leaning back on a more comfortable chair may also work but it is more likely that you will slip into drowsiness instead of meditation. A ‘kneeling chair’ may also be used. There are various designs of these marketed to people suffering from back pain, and they may also be suitable for meditation.

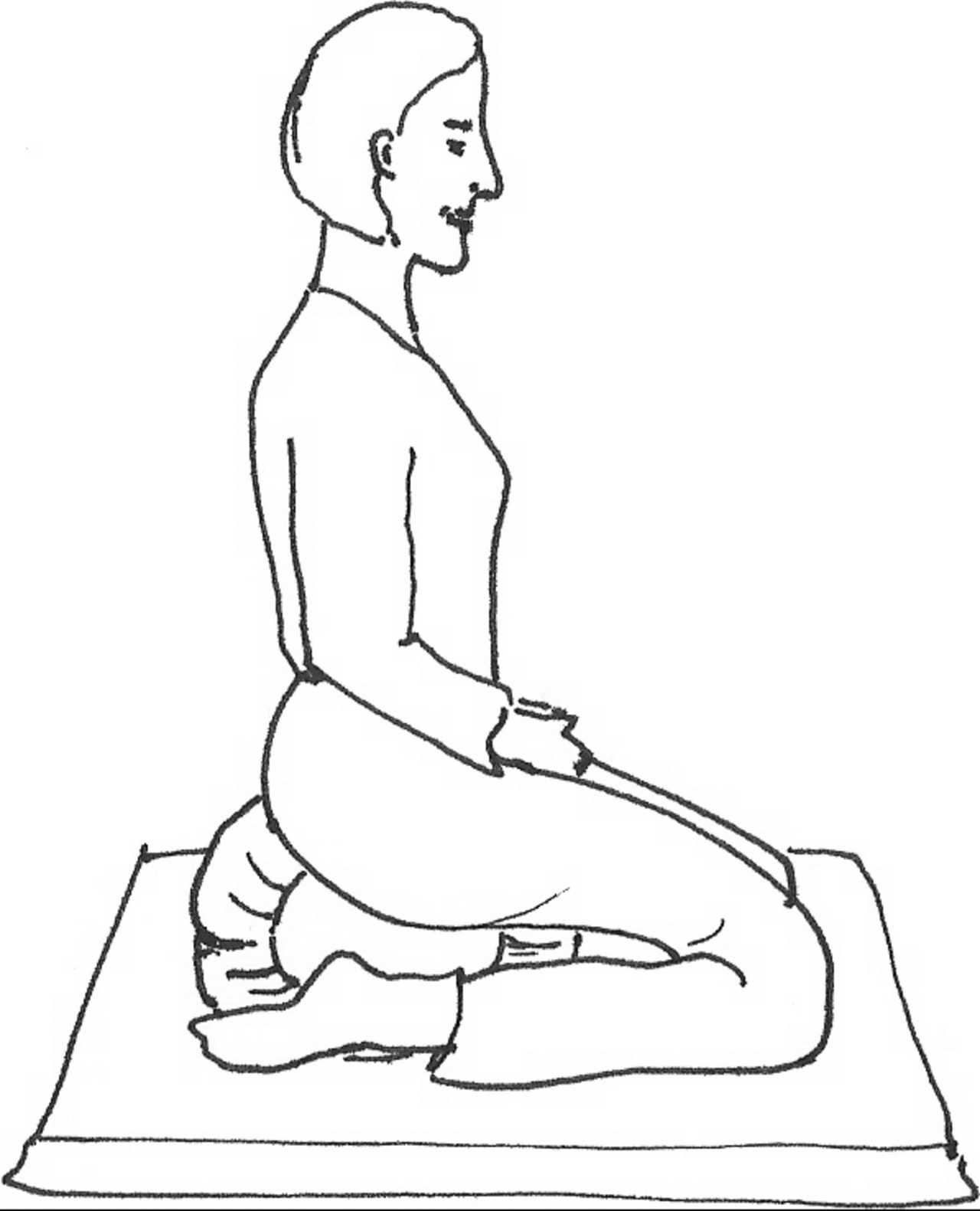

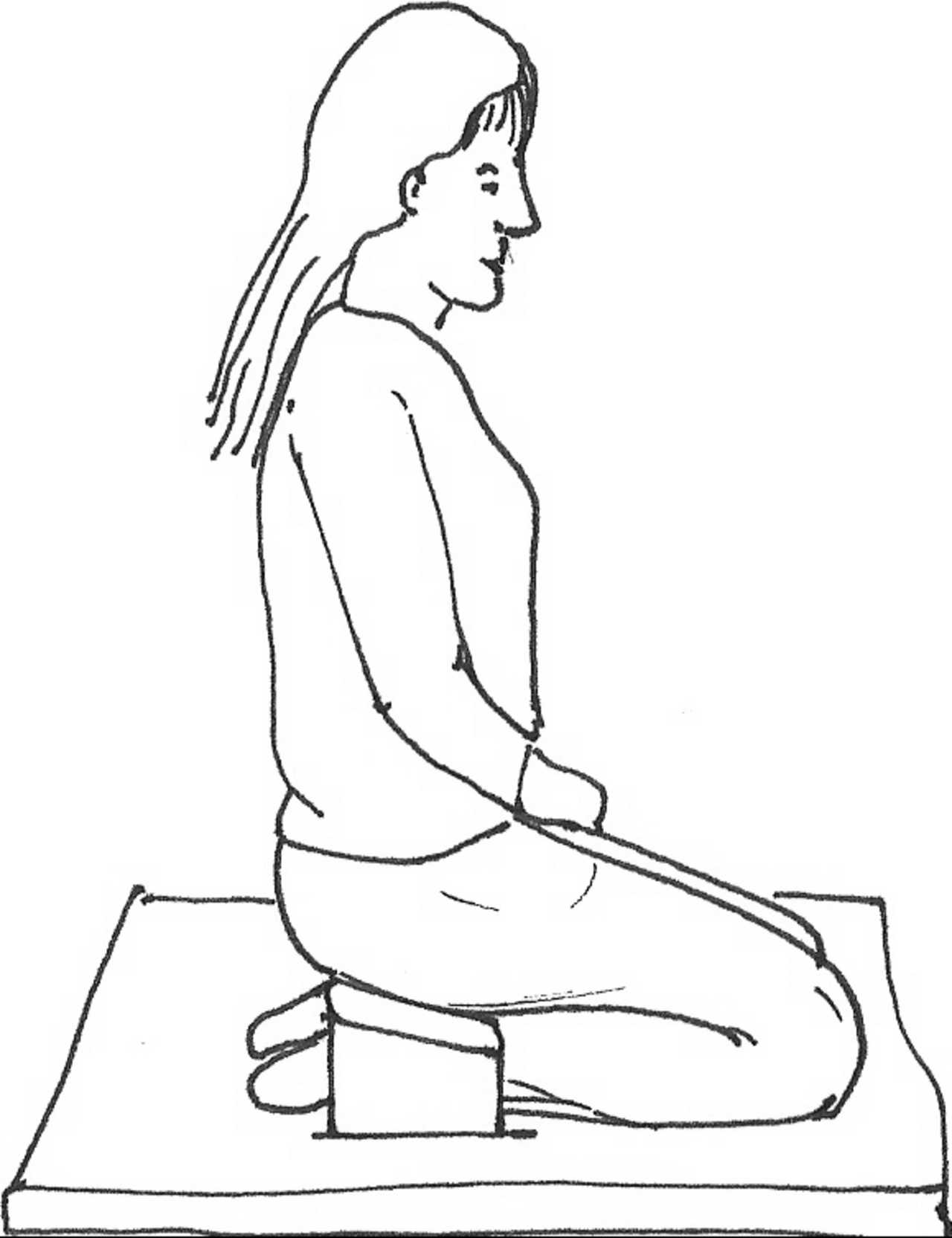

A kneeling position with the body weight supported on a cushion or kneeling bench works well for many.

In the East, use of cross-legged postures such as lotus posture is traditional but these are often difficult for Westerners who have not been brought up sitting cross-legged on the floor.

If you wish to sit this way use a firm meditation cushion and sit on the front edge of it. The traditional Lotus posture is often unsuitable for beginners unless you have trained in yoga and are able to take this position comfortably and without strain. Other cross-legged postures may be considered but don’t use them if they are too uncomfortable or unstable and therefore distracting. Ordinary cross-legged sitting with the knees up in the air is not suitable as it is unstable and soon becomes uncomfortable.

Relaxation in meditation

Once settled into your chosen sitting position check that the body is relaxed. If you begin a meditation session with tension in the body it may become uncomfortable, even painful, triggering you to shuffle position repeatedly and causing disturbance in the mind that you are trying to settle. With a well-balanced posture you will be able to sit still with little need for muscular effort to support the body.

Mentally scan the whole body checking each part and relaxing it whenever you find some tension.

Start with the face. Check that the eyelids are relaxed with the eyes a little open and the gaze looking half-down towards the ground, about 45 degrees from horizontal but not focused on anything in particular. Check that you are not holding a frown or a grimace or any other tense facial expression, and if you are then relax this. If your head is well-positioned and balanced on the neck then the neck muscles can rest. If your head is tilted too far forwards or backwards, or tilted or turned to the side, then there will be tension in the neck muscles. Centre and balance the head, and relax the neck.

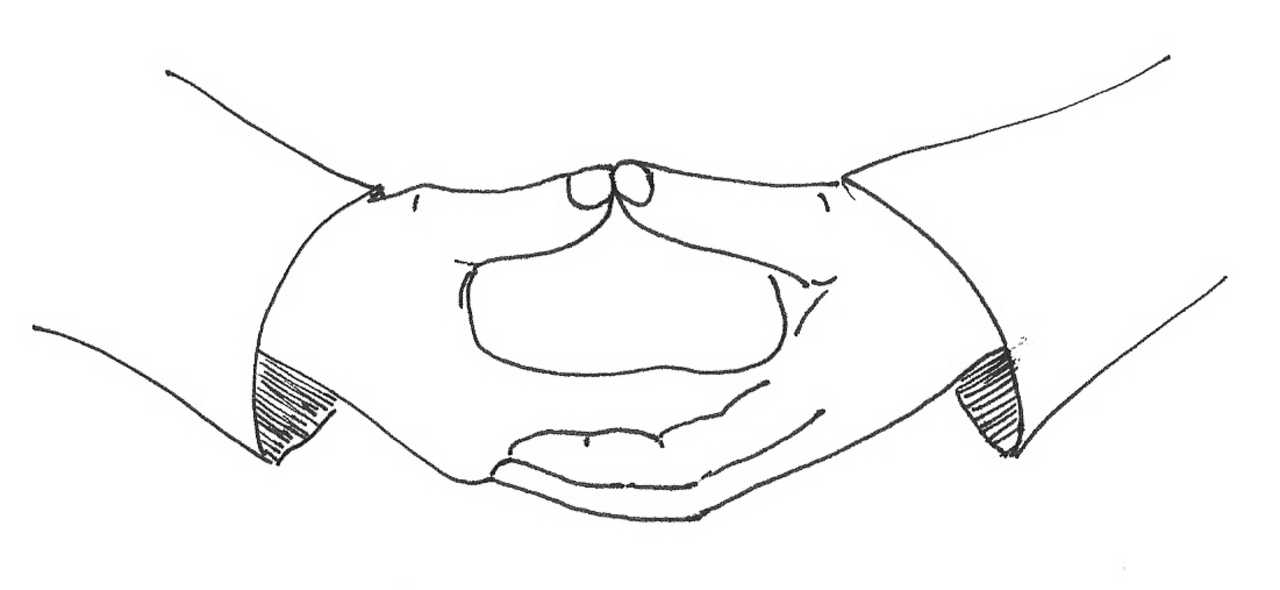

If your shoulders are tense or hunched let them drop and relax. Arms also should be relaxed. The traditional position for the hands is to have the palms facing upwards, one on top of the other, with the tips of the two thumbs lightly touching.

To avoid tension, ensure there is support for the hands and that they do not require any effort to be held in position. You may rest them in your lap but it is often better to place a small cushion or towel on your lap to make a platform on which to rest the hands. In this way there is no effort needed to support them and the hands, arms and shoulders can all relax.

Your back should not be slumping forward, but don’t over straighten it either. Keep it upright with a natural curvature, not leaning to either side, not twisted, and not leaning forward or backwards. As you begin a meditation session you may sway a little left and right, forwards and back, to find the most balanced and relaxed position.

The breath should be natural, and the abdomen relaxed.

There will inevitably be some pressure on your legs and buttocks as they bear the weight of the body, and perhaps some tension in the joints as they are folded into the posture. Ensure that you are not adding unnecessary extra tension by ‘fighting’ against the posture. Just relax into it, accepting the pressure and sensations.

If you become aware of tension developing during the meditation period see if you can relax it away. If not, just allow it to be there as part of the experience of sitting so long as it is not a significant distraction.

How to use you mind in meditation

Once the body is seated, relaxed in a stable position in a suitable environment, what should you do with your mind? You will quickly discover that given nothing to do except sit there the mind fills the space with memories and fantasies, anxieties and desires, or it simply dozes off. Your task at this point is to keep the mind awake and present but relatively inactive. It can be surprisingly difficult to achieve this and this is where the application of a meditation technique or 'method’ is very helpful.

It is often helpful to pick an ‘object’ to focus on and to return the attention to that object whenever the mind dozes or wanders off on a train of thought. This trains the mind in focus and concentration.

There are several possible objects. A common recommendation for beginners is to focus on awareness of the sensations of your own breathing.

The meditation method of ‘following the breath’

There are gentle sensations of breathing at different places in the body. Your first task is to locate and experience these sensations. For some people the most obvious sensation is of the air entering and leaving the nostrils, perhaps feeling cooler as it enters and warmer as it leaves. Others find that it is the gentle in and out movement of the abdomen that is most prominent. Surprisingly there is not usually much sensation of chest movement because in a relaxed resting state the breath is fairly shallow and gentle, coming mainly from the diaphragm with very little movement of the chest.

Select what you find to be the most prominent sensation of breathing, for example at the nostrils or the abdomen, and make this your object of meditation. Set yourself the task of being continuously aware of this part of the body and its sensation. When your mind wanders away thinking about something else, or the awareness becomes dull, bring it back in contact with the sensation of breathing. The attention will often wander away from the breath. This can be rather frustrating but is quite usual. Each time you realise that you have lost awareness of the breath just gently bring awareness back to the sensation of breathing without any fuss or self-recrimination.

‘Counting the Breath’ as a meditation method

If the mind is not yet trained to concentrate then remaining attentive to the sensations of the breath can be difficult. You may find that you are distracted much of the time. It can be helpful to strengthen the method by adding in counting of the breaths. Taking on the task of counting the breaths, in addition to experiencing the breath sensations, leaves less opportunity for the mind to wander. There are various styles of counting, the basic being to count the exhalations silently. As you breathe out, count ‘one’ to yourself. On the next exhalation count ‘two’, and so on.

Typically within a few breaths the attention will wander. When you realise that it has wandered then start again at one on the next exhalation. If your attention is fairly stable and you manage to reach a count of ten breaths without wandering, start the count again at one and repeat the cycle.

Natural Breath Meditation

It is important when focusing on the breath sensation that you allow the breath to move naturally. Breathe through the nose with the mouth closed. Do not alter the breath to be deeper or shallower, slower or faster – just experience the sensations of natural breathing. If the natural regulation of the breath is overruled this can lead to dizziness or chest tightness. Some people find that when they observe the breath it is difficult for them to avoid changing it, and for such people the methods of following or counting the breath may not be suitable. They can use an alternative object of focus for their meditation.

Other Methods of Meditation

Common alternative objects include: a silent recitation or mantra; the gaze resting on an external object such as a flower, a candle, an image or statue; a continuous or frequent sound such as flowing water, or it could be the background hum of traffic or city noise. The main criterion for choosing an object of meditation is that it should be something stable and simple such that it does not stimulate the mind into thinking.

Another good option is to place the awareness on the overall experience and sensation of the body as it is sitting. This may include awareness of breath as a part of the experience, but breath is no longer the prime focus. Body awareness includes the sensation of the pressure points of sitting i.e. the buttocks and knees, the balance of the spine and neck, and relaxation of abdomen, arms and shoulders. It may also sense the light touch of clothing, or draught, or sunlight on the cheek. This awareness also includes any emotional feelings that arise and are sensed in the body.

All these are experienced, but none are elaborated by internal conversations which might draw the attention away from the next moment of body awareness. In this way one is very present in the experience of sitting, but is doing nothing else, and this practice is known as ‘just sitting’. This method can be harder to establish and sustain than more narrowly focused methods because the wider awareness notices multiple sensations and feelings which may trigger trains of thought. But if you are able to sustain this wider awareness then you are in a good position to take up the other principal aspect of meditation, to investigate the mind.

Developing the meditation, investigating the mind

The methods described above are primarily methods for calming the mind, generating concentration and focus. These are valuable in themselves but can also be regarded just as preparation for taking the meditation practice another step, into the investigation of mind. Once the mind has calmed down we begin to find ourselves in a state where the thoughts are no longer tumbling over each other creating noise and confusion in the mind. We may be able to observe each thought as an individual process which has a beginning, a middle, and an end, which was previously unobserved as each thought was interrupted or overshadowed by other thoughts. We may even experience a mind with no thoughts, a mind resting between thoughts.

With a mind in this calmed condition we have the possibility of investigating the nature of mind and thoughts directly in our own experience. What is mind and where do thoughts come from? We can switch our object of concentration from some arbitrary choice, such as breath or candle, to the mind itself, observing our mind while thoughts and feelings and sensations arise in it and pass through it. With our improved concentration we maintain attention on the mind, noticing when we are drawn away by something which arises within our awareness. We practise focusing on the mind itself and are less involved with its contents.

This requires a stable wider open awareness which can experience phenomena without becoming engrossed in them such that other phenomena are overlooked. Cultivate this by practising it through regular formal sitting meditation, and also by continuing this wider awareness when going about one’s everyday life.

Handling Difficulties in Meditation

Meditation is not always easy. There are the practical difficulties which can be very real of finding undisturbed time and place for sitting meditation. There can be difficulty finding an appropriate posture which supports you well enough for a period of meditation without becoming too uncomfortable. The mind can be hard to train and calm down, and is also prone to being drowsy and switching off. Developing the practice towards an open awareness can be tricky because the mind is so easily caught by, and lost in, trains of thought.

It is often said that meditation cannot be learned from a book, so why have I written the instructions above? These are to be taken only as an overview and as pointers for beginning, and not as a whole description of how to practise meditation. There are tips and strategies for dealing with the difficulties that arise and they are best taught in person and individually, adjusted to your particular circumstances. For further development of your practice it is best if you consult a meditation instructor, or a meditation master, rather than relying too much on written materials. Bodhidharma, the founder of the Chan Buddhist tradition in 5th century China said,

“It’s true, you have the Buddha nature. But without the help of a teacher you’ll never know it. Only one person in a million becomes enlightened without a teacher’s help.” 1

Deepening the Practice of Meditation

Unfortunately it is rare to click immediately with meditation. Initially it can even seem to be going ‘backwards’ as you become more aware of just how busy and chaotic your mind can be and yet do not immediately get any sense of calming. But persistence is the key and this takes several forms.

In general it is best to stick at it even if it doesn’t seem to be going well as it is sometimes necessary to push oneself through a difficult patch. This applies both to a single meditation period and also to a pattern of ongoing practice. But don’t make it into an unwelcome chore which may lead you to disengage from the practice. This requires judgement and is an example of a situation where contact with a teacher may be helpful for advice on how to proceed.

Rather than meditating rarely or irregularly make it a regular part of your life, preferably daily. The amount of time that you can give to it will depend on your lifestyle and commitments but most people can manage 10-15 minutes a day, perhaps 30-40 minutes, and a small amount of regular meditation is better than infrequent longer periods.

Do occasional extended sessions such as one-day retreats or longer residential silent retreats in which you will sit multiple meditation periods. It is usually most practical to join some organised event where someone else is taking care of practicalities such as timetabling and food, and exercising between sitting periods, so that your meditation is not disturbed by concerns about these. Longer sessions of repeated meditation periods have a ‘cumulative’ benefit. The calming effect of one sitting period may not seem very great, but you may enter the next period in a better condition and the next in an even better condition. Over a longer session like this, without distractions between the periods, you may reach a depth that is not often encountered on everyday single sittings.

Allow the practice to flow from the formal sittings into the rest of your life. There is no need to cut off awareness or busy the mind just because you have reached the end of your designated meditation period! Continue into your life with awareness and stability, and observe (instead of being caught by) your tendency to reactivity when encountering people and situations. This is the cultivation of mindfulness in daily life and is a crucial step in developing your practice.

Notes

1. The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma, Red Pine, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989

- First edition, September 2015 ©Simon Child. Minor amendments July 2025

- Cover art ©2015 Ros Cuthbert

- Illustrations ©2015 Jane Spray

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: For Newcomers Highlighted 2015 Other Articles Simon Child

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-410