Is the View of Practice More Important than Practice Itself

Published with permission and lightly edited from Chan Magazine. Spring 1994 11-15.

Shifu, I have a question. A Chan aphorism says, "The practice is important but the view of practice is even more important." It seems to me this is a contradiction of Chan because any view I hold must be subjective and a distortion of truth and therefore an obstruction. If the ego goes away in the experience of practice what does it matter if the person is Atheist, Buddhist, Christian, Muslim or anything else. If you say only Buddhists can have such an experience is not this elitist?

Shifu answers: The saying you refer to is a paraphrase of a line which reads "What one knows or sees is more important than where one is stepping." You should not translate "what one knows or sees" by the word "view" because a view is something that can come from one's learning. By contrast the Chinese phrase refers to direct experience. In the Lotus Sutra there is a saying, "To open what the Buddha knows and sees; to reveal what the Buddha knows and sees; to realise what the Buddha knows and sees; to enter what the Buddha knows and sees." What the Buddha knows and sees is emptiness - no form - no attachment - no conditioned phenomena.

We can translate this line as "What one knows and sees is more important than what one is doing. Here "what one knows and sees" refers to what the Buddha knows and sees. How can a practitioner understand this?

There is certainly the case of one who has "experienced the nature" and has entered what the Buddha knows and sees. But how can others really know that what they know and see is what the Buddha knows and sees? One has to gauge experience against the teachings of the Buddha, that is the Sutras. Practising with diligence, studying the Sutras, keeping the precepts, hearing teachings - all these are what one does. But this is not as important as what one knows or sees. Without enlightenment one cannot really know and see what the Buddha knows and sees.

If one has a good teacher then reading the sutras is less important. A sound teacher should be able to tell whether an experience is genuine or not, shallow or deep. If there is no enlightenment experience the teacher can point to the problem or blockage in practice - the obstruction or the attachment that prevents insight.

This aphorism is not advising people to abandon practice; rather it says that practice is important but what the Buddha knows and sees is even more important. Without the guidance of the Buddha's experience people will not be practising Buddhadharma correctly. They would be engaging in "outer paths". Before enlightenment, practitioners need the guidance of what the Buddha knows and sees. After an enlightenment experience they still need to check their experience against the teachings of the Buddha to see if it is truly what the Buddha knows and sees.

Tasting wine, evaluating wines and sipping them is not the same as falling into the barrel. Then there is no separation from the wine and to speak of thirst is no longer relevant. A shallow Chan experience lasts for a short time and a deeper one lasts longer. With a deeper experience a person sees emptiness more clearly.

Even if you have had no enlightenment experience, an intellectual grasp of what the Buddha knows and sees will prevent you venturing far down the wrong path. You may even be able to guide others in practice but you will not be able to confirm another's possible enlightenment.

If a teacher has neither comprehended intellectually what the Buddha knows nor tasted it in an enlightenment experience then he or she is probably practising an outer path and leading others into error. People often practice with some expectation in mind - an idea that there is something to be gained. This leads to problems.

Many practitioners have experiences of a supposed unchanging totality or eternity but this is not what the Buddha knows and sees. People from many traditions have this experience and they may constitute a first opening to enlightenment. Such experience is however not an experience of no-self, of emptiness.

Much of Buddhism is not too difficult to understand and communicate. You may develop a sound intellectual understanding through appropriate literature and armed with knowledge you may instruct others in a rudimentary way. Such a teacher should not attempt the big issues. Most importantly he or she will have no capability of confirming or disavowing someone else's supposed enlightenment experience. If you are intent on teaching others about Buddhism or leading a meditation group you should first get permission from your teacher.

Problems arise if someone uses religious experience to interpret the sutras. One should use the sutras to interpret religious experience. That is why one should work with a good and qualified teacher.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

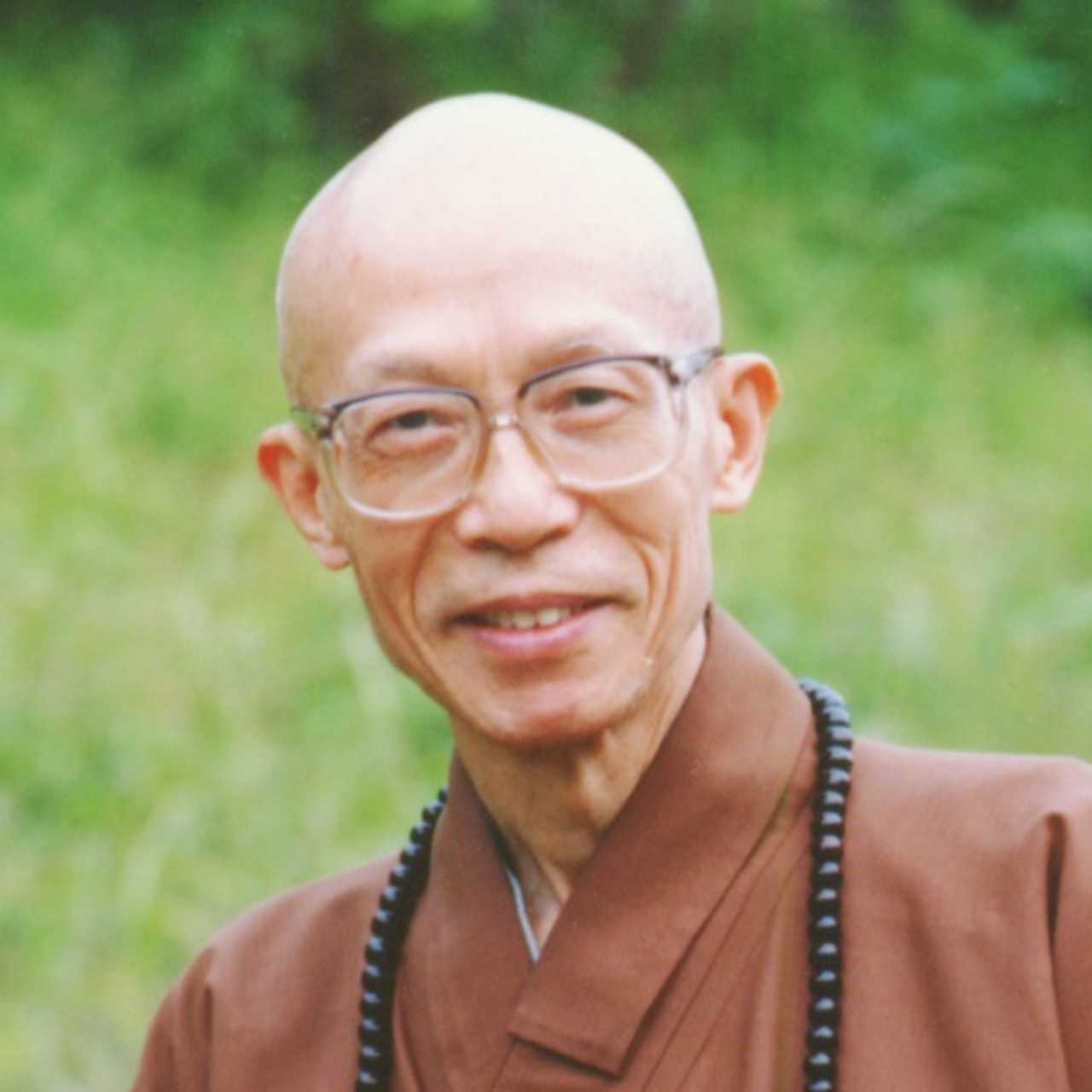

- Categories: 1994 Other Articles Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-515