No Going by Appearances

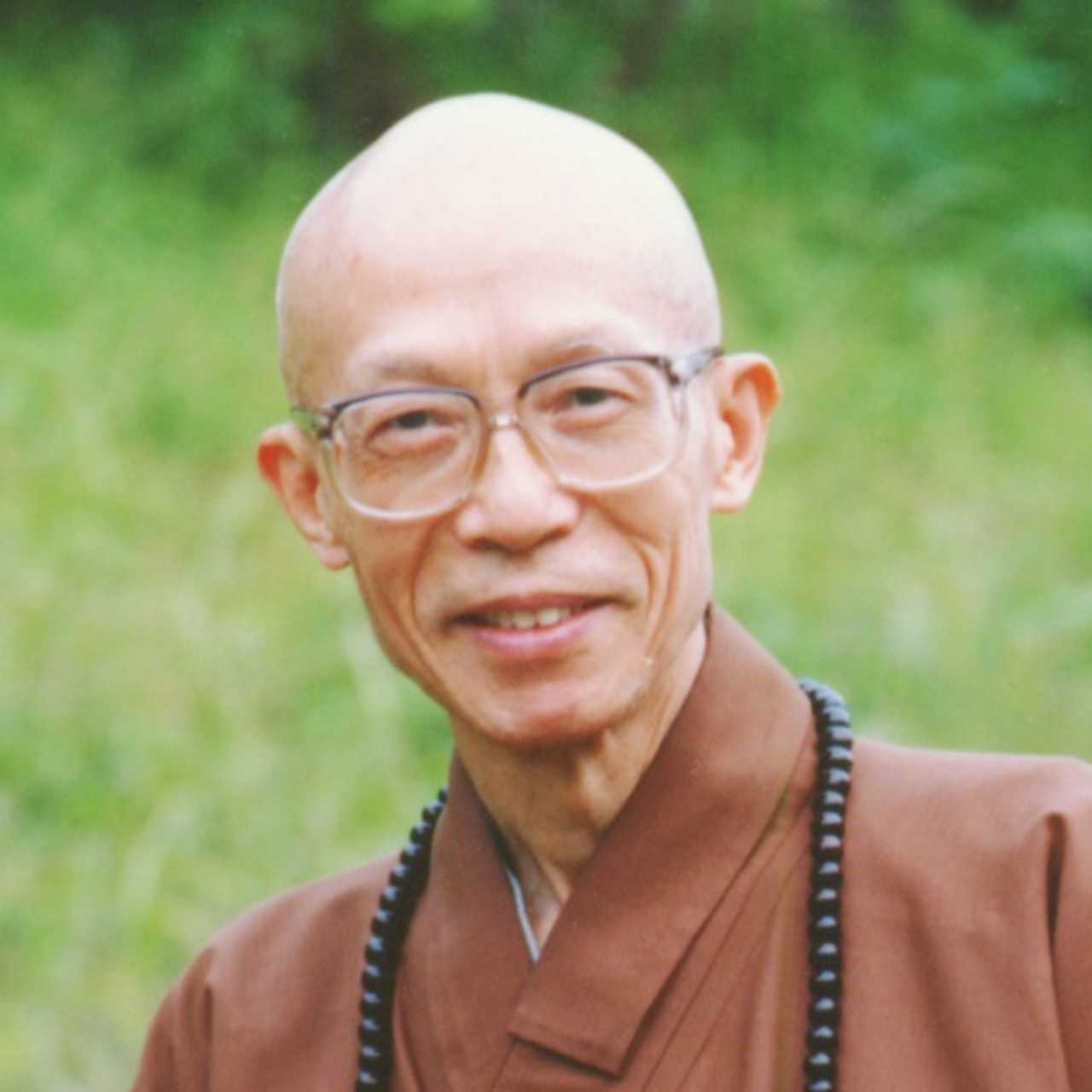

A talk by Chan Master Shengyen, Excerpted from Chan Magazine and lightly edited.

Outwardly like a complete fool,

Inwardly mind is empty and real.

Often, it is a monk who appears slow and some-what dumb who is the great practitioner; and the monk who appears to be extremely sharp and knowledgeable is the one who often needs to practice more diligently. Do not concern yourself with or waste time wondering what your experiences may mean, whether you are making progress or not, or how you appear to others. Stay with your method and the rest will take care of itself.

Looks can often be misleading. Some monks who appear to be foolish or dumb may actually be deeply enlightened. There are many stories in Buddhist history that speak of enlightened monks who were often overlooked by others because of their behaviour or appearance. Often, these monks would disregard many of the minor monastery rules, making them appear to be disrespectful, ignorant, or absent-minded.

One such story involves Ming dynasty Master Han-shan (not the poet) and his experiences with a monk while visiting a monastery. This particular monk had contracted a disease that had grotesquely bloated his body and had turned his skin a sickening yellow colour. He was shunned by the rest of the monks in the monastery because they were disgusted by him. He spent most of his time alone because no one would go near him. Still, he was grateful for being in the monastery, and when he asked for a work assignment, he was given the task of cleaning the bathrooms.

Master Han-shan developed an interest in this man because every morning he noticed that the bathrooms were spotlessly clean. Han-shan inquired and was directed to speak to the sick monk. This monk told him that he would clean the bathrooms every night while everyone else slept because he himself had no-where to sleep. After he was finished with this assignment, he would spend the rest of the evening in the Meditation Hall waiting for morning service.

After hearing this, Master Han-shan had great respect for the monk that everyone else avoided. As it turned out, Master Han-shan had a few, long-standing problems with his meditation that he could not resolve. He thought that there might be more to this monk than anyone knew, and so he told him about his problems and asked for guidance. Master Han-shan's intuitions were correct, because the diseased monk regarded the problems as a simple matter and offered perfect advice.

We can gain a few insights from this story. One, this monk felt no need to advertise his experience and attainment; and two, he was neither depressed over nor deterred by the preconceptions of and treatment by his peers. He did not indulge in arrogance or self-pity. How affected do you think you would be in similar circumstances? Would great spiritual experiences fill you with feelings and thoughts of pride and superiority? How would you react if you were the subject of constant ridicule or harassment? Worse, how would you feel if you were ignored and shunned? Would you have the same resolve and equanimity as did the monk in the story?

Usually, the more deeply enlightened a person is, the less he or she will stand out in a crowd. Once, someone made a long pilgrimage to Master Hsu-yun's residence in order to meet the great, contemporary master. The man spotted a nondescript monk spreading manure in a field and asked if he was going the right way and how long it would be before he arrived at Hsu-yun's monastery. The monk in the field annoyed the traveller because he asked questions about his reasons for wanting to visit Hsu-yun. The traveller did not want to be bothered by this ordinary monk, but as you may have already guessed, the manure-spreading monk was Hsu-yun himself. My master, Lin-yuan, also did not have the appearance of a great, awe-inspiring monk. It was the same for me when I was younger, but now people show me more respect. Some may say it is because of my personality and reputation as a Chan teacher, but I suspect it has more to do with looking old and my hair turning white.

These two lines of verse refer to the appearance of one who is already enlightened, but I encourage all of you not to wait for enlightenment to cultivate such an attitude. You will have far fewer vexations if you have the attitude of the diseased monk in the Han-shan story. Pretentiousness is the source of many problems. Whatever you are doing, just do it. Do not concern yourself with the approval or disapproval of others. Do not think about whether you look like a fool or not. People waste so much time and energy trying to impress or take advantage of others.

How many of you would accept a job as a cleaner of bathrooms? Would you consider the job to be below you? How many of you would be willing to let someone else get the better of you in certain situations? If you cannot do even this, then you have not learned much from practice. If in your mind you are clearly aware of what is happening around you or to you, then it does not matter what others perceive or believe. You may appear to be foolish or gullible to others, but in your mind you know you are not. Cultivating such a personality can also be transformative for others, because people will eventually realise that you are not a fool and that, in fact, you are accepting them. Such behaviour gives others permission to be more honest and less pretentious.

One of my students in Taiwan once told me that he is clear and sharp when he listens to my lectures, but when he is working he feels dull and one step behind everyone else. Then he turned to me and said, "You often appear like that yourself, Shifu. If I didn't already know you and were to see the way you act sometimes, I would think that you were a stupid idiot."

I did not expect such a comment, and so I responded, "A person with great wisdom is like a fool." But then I added, "Since I'm not a person of great wisdom, you are probably right. Perhaps I am just a fool."

I am relieved that because of my practice, I have grown less sensitive to things other people say and do; otherwise, I probably would have been insulted by this man's comment.

Actually, it is true that I am sometimes slow-acting. I could claim that it is because I am mindful about my every decision and movement; but the truth is that sometimes, I do not know what to do. Once, two of my disciples were arguing and fighting right in front of me. If I had adhered to the rules of the temple, I would have asked them to leave. Instead, I closed my eyes. I sat there, doing nothing, and then left.

The same person who called me a stupid idiot witnessed the entire interaction, and he caught me in the hallway and asked, "You are their Shifu. What are you going to do about it?"

I said, "I don't know." Ultimately, I talked to each disciple, but not until they had finished arguing and had calmed down. I did not see any point in trying to reason with them when they were in the middle of a fight. Nothing would have gotten accomplished. By waiting until they were calm and rational, I was able to talk to them without shaming them or antagonising them further. Also, because they were clearer, the problem was quickly and easily resolved. I still am not sure if my strategy was foolish or wise, but at the time, it seemed to be the expedient thing to do.

In our daily lives, we should train ourselves to be less sensitive to the perceptions of others. Like enlightened beings, we should not be afraid to appear outwardly foolish. Whenever you find that you are filled with vexation because of embarrassment or over-sensitivity, reflect, "Why am I not cultivating outward foolishness and inward clarity?" This is not an easy task for most people, even for Buddhists and Chan practitioners. Moreover, we are not enlightened beings, so we cannot expect to act this way all the time. But it is definitely an attitude worth cultivating, and I encourage you to make it an integral part of your daily practice.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2000 Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-124