Not Knowing is Knowing

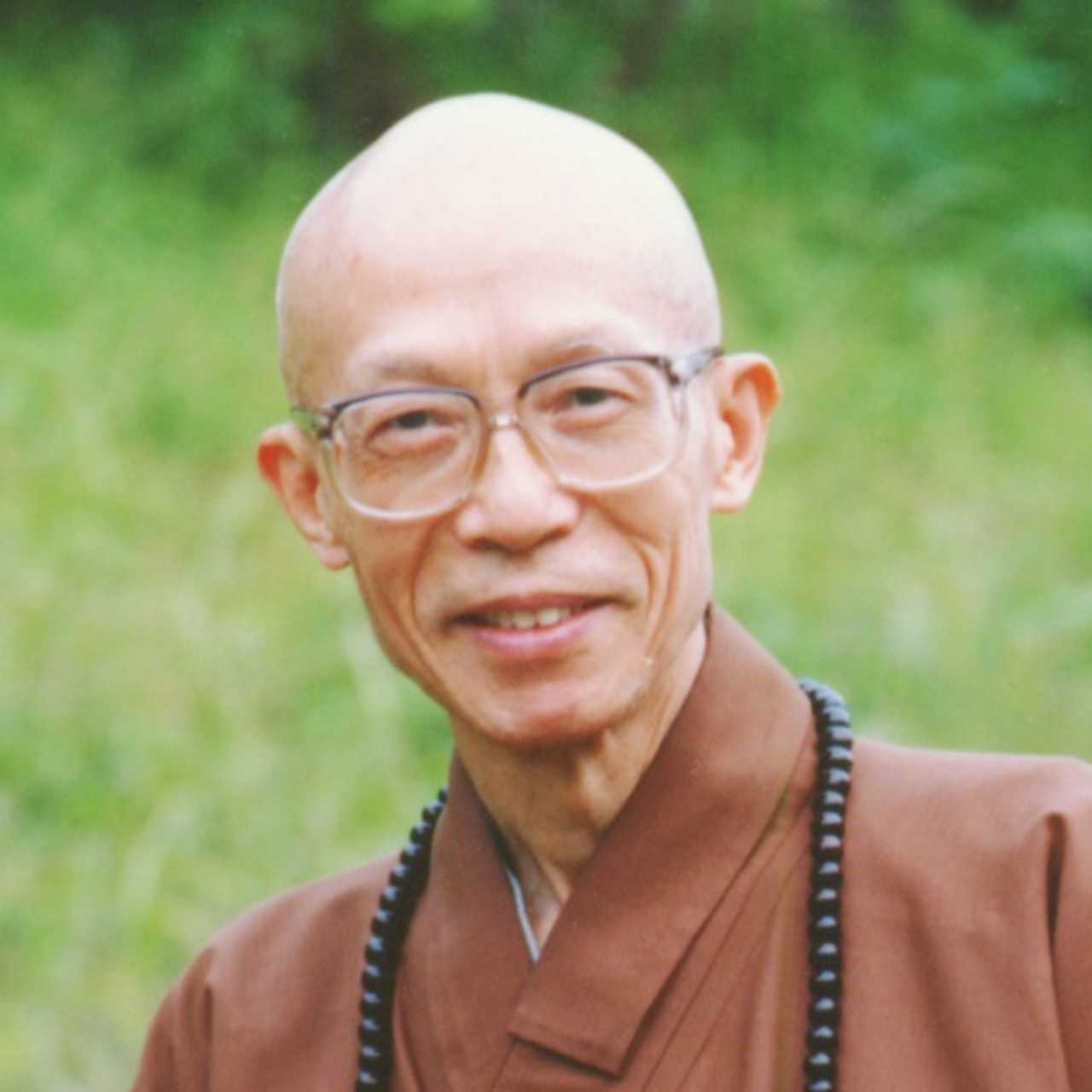

A lecture given on retreat at the Meditation Centre, New York, reprinted by kind permission from the Chan Magazine Fall 1993 p19 and slightly edited for this presentation.

Knowing dharmas is not knowing Not knowing is knowing the essential... The highest principle cannot be explained: It is neither free nor bound Lively and attuned to everything It is always right before you. 1

The Chan sect does not rely on language. if you understand Buddhadharma only with your intellect, then you do not understand it at all. Some people study koans and try to solve them intellectually. They think they have the correct answers, but it is impossible to solve koans in this way. Any effective Chan master will detect the trace of intellect in the answer. You can indeed examine the concepts and principles of Buddhadharma intellectually but this is only one type of understanding. Enlightenment is another matter, not stemming from mere academic knowledge. So far as enlightenment is concerned, thinking that you know is ignorance!

Those who have studied sutras may think that they know Buddhadharma, but this is as if they were looking at the world through a narrow pipe, a tunnel vision. what they see is limited, channelled. Their understanding is partial. The essence of Buddhist teaching is wisdom and compassion.

Of course Buddhist practitioners know they should be compassionate but inevitably someone irritates them. It is impossible for ordinary people to be compassionate all the time with everyone. Their wisdom is shallow and limited. Indeed I know a monk who is nice to everyone but he has a habit of tearing up his clothes and books. He confessed to me "Since I cannot show my anger to others, I release it in this way". This isn't too bad. At least he doesn't beat himself up. Still, his wisdom and compassion are not deep.

Being human we get angry. If you want to deal better with your anger, do this: whenever you feel angry, relax your stomach, then say to yourself, "OK, now be angry!" Its more difficult to be angry once you are relaxed. When one is angry the stomach tightens.

To progress on the Path it is essential to realise that you are ignorant. The more worldly knowledge one possesses, the more vexations accumulate. Knowledge is acquired through learning, but knowledge has its limitations. One cannot know everything. If you know the details but not the underlying principles, then you become lost in a sea of facts.

In Sakyamuni Buddha's time there was a Brahman who thought he knew everything. Hearing that the Buddha was a man of great knowledge he challenged him to a contest. First he tied his head and stomach with copper bands. Sakyamuni asked him what the bands were for. He said "I have so much knowledge I must bind my head and stomach so that they do not explode!" Then he challenged the Buddha "If you ask a question and I cannot answer, I will be your disciple. If you lose, then you be my disciple."

The Buddha said, "There's nothing I cannot debate, but I have no suggestions for a topic".

The Brahman said "How can we debate if we do not have a topic?"

The Buddha replied, "As long as there is something, that something can be refuted. I have nothing and therefore you cannot defeat me. You, on the other hand, have so many things in your head and stomach it will be easy to defeat you."

Those who have no understanding of Buddhadharma may begin by studying its concepts and principles but those with some intellectual understanding should be encouraged to practise. when you are successful on the path you will realise there is no such thing as Buddhadharma. You might speak about it but that is only a response to those who do not know about it.

It is good to nurture faith as you practise. Try not to analyse everything or speculate endlessly. Refrain from asking so many questions. Knowledge is bad for practise because it is not a genuine understanding based on personal insight. when I practised in Japan I had just received my doctorate. The master knew this and took particular delight in giving me trouble! Turning to books for guidance instead of working with a master means one will remain experientially ignorant. This is what the first line above implies.

"Not knowing is knowing the essential" can be illustrated by a story. A boss once interviewed ten people for a job. Nine were very good at exams and boasted to him of their qualifications. The tenth said he knew nothing but he was willing to learn, ask questions on the job and check with the boss when he was in difficulty. He was hired. Similarly it is best that you come on retreat without previous knowledge. Begin as if you had no past. Those who think they know everything cannot move forward. Those who have wisdom may appear stupid because "knowing everything" is as if they know nothing. Their stomachs are infinitely large, without boundaries. Having limitless stomachs one cannot say they eat. Knowing "everything" one cannot say they know.

Academic knowledge is limited. Not knowing is true knowing. One knows truly only when one has the wisdom of emptiness. Wisdom is then limitless.

Once a woman rang me from California. She said she wanted to attend retreat because she had read my books and the information in them was in accord with what she knew. The person who thinks she knows, doesn't know. If she thinks she doesn't know she has a mind to learn. This is the correct mind for practice. The greatest obstacle is looking at Buddhadharma with eyes full of past experiences and book learning.

Not knowing, one can begin to know. A blank sheet of paper can be used but once scribbled upon it is useless. Be like a blank sheet, cut yourself off from previous thought, stay with the present. On retreat, clean off the blackboard.

Not knowing is important. When a thought arises, say "I don't know you. I don't recognise you !" Working on a koan it is useless to think or speculate. Once a participant on retreat came to me after only two hours of working on a koan and told me he now knew that "wu" was Buddha nature. I asked him how he had realised that and he told me that the Buddha's teaching said so. But he was perplexed because he did not feel any different. I told him that any "enlightenment" that came so easily and in such a manner was just a joke. I asked him to keep such answers for examination papers, not for Chan retreats.

If at all times on retreat you are in a state of not knowing, then you will not know what you are eating, where you are walking, what you are doing, yet you will feel comfortable and light and experience power in your practice. At such a time you can truly work on a koan. Great doubt will arise quickly and you will benefit. if your head is loaded with knowledge then using a koan is a waste of time. My Zen master in Japan had good reason to scold me. My mind had been loaded with knowledge.

1. From the Song of Mind by Niu-t'ou Fa-Jung c594-657 AD). in: The Poetry of Enlightenment Master Sheng Yen: Dharma Drum. New York p33.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: For Newcomers 1993 Dharma Talks Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-112