Reading Sutras as a Spiritual Practice

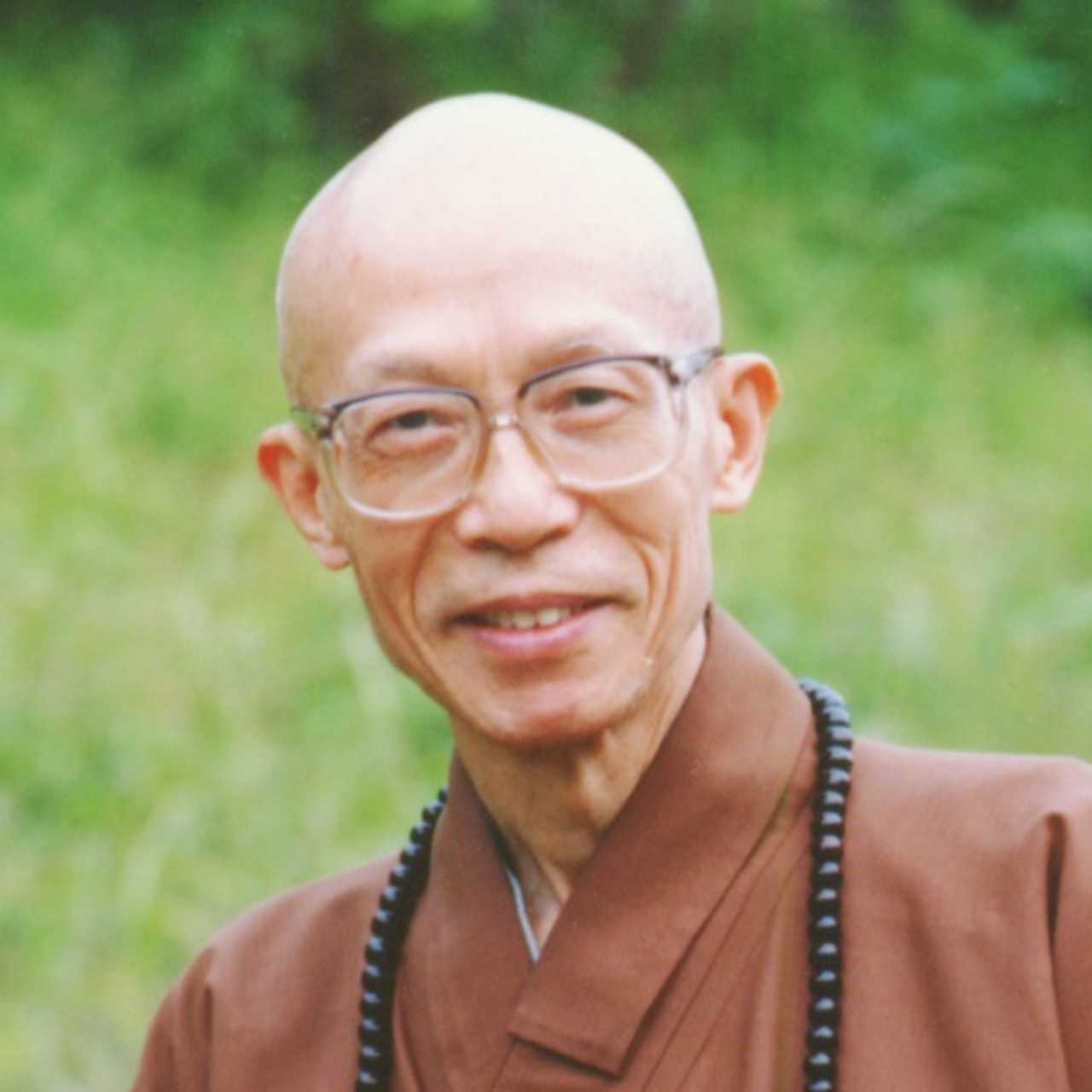

A talk delivered at Tibet House in New York City, on 5 November, 1994 and edited by Linda Peer and Harry Miller, edited with permission for NCF by John Crook 1998. In this talk Shifu tells us about the traditional uses to which the Sutras are put in China. Some of us may like to make use of these methods. For Westerners Sutra reading is also important. In particular the oldest Sutras, the ones Ananda so carefully remembered and which begin: "Thus have I heard..." reveal for us exactly what Gautama the Buddha was like as a man teaching, instructing and dealing with everyday matters of life in the 6th century BC. Readers unfamiliar with the Sutras might well begin there, meeting the Tathagata in person in his daily life. Contemplating his actions and sermons is the root of Buddhism. (Eds.)

The Buddhist scriptures are divided into three categories. The Vinaya and Sila are moral codes and precepts spoken by the Buddha, the Shastras are commentaries on the Buddha's teachings by Bodhisattvas and great masters, and the Sutras are discourses spoken by the Buddha. Together they make up the Tripitaka. Each kind of scripture has special benefits. The Sutras are particularly concerned with the mind, and their function is the cultivation of samadhi and wisdom. The Vinaya helps us to behave in a correct and proper way, so that our actions, speech and thoughts accord with Buddhadharma. Finally, the Shastras help us to cultivate our analytical understanding of Buddhadharma.

The Heart Sutra is common to all Chinese Buddhist sects. Although the teachings and practices of the Chan school are not based on written words or language, we still recite Sutras. Perhaps this is surprising; the old masters often seemed disrespectful of the Sutras. Once a monk asked Master Lin-chi (Jp. Rinzai), the founder of one of the two schools of Chan which survive into our time, about the usefulness of the Sutras. Master Lin-chi said that they are very good for wiping up pus! A monk saw Chan Master Yao-shan reading a scripture and said, "Chan is not based on written words and language, so what are you doing reading scriptures?" Master Yao- shan replied, "I only use the scriptures to shade my eyes."

We can see from these stories that Chan does not place strong emphasis on scriptures. However, Chan teaching can be traced back to two Sutras, the Lankavatara Sutra (Sutra on the Descent to Sri Lanka) and the Diamond Sutra (Vajrachchedika Prajnaparamita-Sutra). Additionally the Heart Sutra is recited every day in Chan monastic communities.

The famous Sixth Patriarch, Hui-neng, was illiterate, but he became enlightened after overhearing a phrase from the Diamond Sutra. Obviously, reciting scriptures can be very useful, and we should do it. We may even be the catalyst for someone else's enlightenment!

Both the Chinese and Japanese traditions teach us to use the scriptures and the recitation of scriptures as a mirror in our practice. Reciting a Sutra should cause us to reflect on our actions of body, speech and mind. Do they accord with the Sutra we recite? If not, we should change our actions to pattern them on the scripture.

There are many methods of Sutra reading and recitation. We can read or recite silently. We can 'read' a Sutra, which means to read aloud, or we can 'recite,' which means either chanting aloud or reading a Sutra over and over again. We can also write out, or copy, a Sutra as a practice. And we can 'uphold' a Sutra. In 'upholding', the practitioner retains the Sutra in his or her memory at all times. For instance, you might recite from memory and try to uphold the Heart Sutra for days at a time. This is often done silently. Why? Because, for instance, when you go to the toilet it would not be respectful to say the Sutra out loud. There is also a practice in which a practitioner who specializes in reciting a particular Sutra also explains the Sutra to others. 'Recitation through the physical body' is another method. This may sound strange, but it simply means to recite while kneeling. Furthermore, in the Lotus Sutra a method of reciting the Sutras while doing prostrations is taught. I will explain how this practice is done later.

Buddhists have probably practiced Sutra reading since the beginning of Buddhism. Early Buddhist texts on practice call recitation one of the three major practices. The 52nd fascicle of the Middle Length (Madhyama) Agamas, the earliest collection of Buddha's teachings, encourages practitioners to uphold and recite the Sutras, the Vinaya and the Shastras, as methods of practice. The Ten Pratimoksha (the Ten Moral Conducts) and the Martivasaka-Vinaya (the Vinaya in Five Sections) likewise recommend the practice of reciting the Vinaya.

The scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism again speak of the merit and function of Sutra recitation. The Lotus Sutra (the Saddharma- pundarika Sutra) is composed of twenty-eight fascicles, of which eighteen recommend the practice of Sutra recitation and 'adorning', or purifying, the six sense organs through scriptural recitation. The Savanaprahbasotama Sutra (the Golden Illumination Sutra) says that reciting and upholding the Sutra will enable one to go beyond the ocean of suffering and attain non-regression of Bodhi mind. In other words, the realization of the enlightened mind.

In the Pure Land sects, which are part of the Mahayana tradition, two major scriptures are used, the smaller Sukhavati-vyuha Sutra (the Sutra of the Land of Bliss) and the Amitayurdhyana Sutra (Sutra of Visualization). They are asssociated with Amitabha Buddha of the Western Pure Land, the major Buddha of the Pure Land sects, and they, too, describe upholding and reciting the Sutras.

The Brahma Net Sutra or the Brahmajala, contains moral codes, and I believe it is special to China. It recommends reciting the Sutras on behalf of the deceased in order to transfer merit to them.

Following all these recommendations, recitation has become one of the fundamentals of Buddhist practice in China. Some of the commonly recited Sutras are the Sukhavati-vyuha Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, the Heart Sutra, and the Vimilakirti Sutra. When I was a novice monk, my master told me to start by memorizing the Heart Sutra. Next, he told me to memorize the Sukhavati-vyuha Sutra, and after that, the Diamond Sutra. Finally, my master told me to memorize the Lotus Sutra, which is eighty thousand words long. I never memorized the whole Sutra, but I memorized most of it, and it has been of great help and benefit to me. If you want to learn to uphold a Sutra as a practice, you cannot read it; you have to memorize it. You have to retain it in your mind. Only when you can retain the Sutras in your memory can you practice upholding them instead of just reciting them.

It is also beneficial to memorize mantras and dharanis in addition to Sutras. The word 'dharani' means complete or universal upholding. A dharani completely encompasses the meanings and powers of whatever it is associated with, so reciting it is a powerful practice. For example, a dharani may be associated with a Bodhisattva. If you uphold that dharani, your practice is an expression of the merit, virtue and attainment of that Bodhisattva. In the same way, a dharani associated with a Buddha is an expression of the merit and virtue, practice and power of that Buddha.

Chinese Buddhists often memorize dharanis such as the long dharani from the Surangama Sutra, the Great Compassionate Dharani and the dharani from the Lotus Sutra. When I was young, my master told me to memorize a dharani from the Lotus Sutra. He said, "This dharani is very difficult to pronounce and to memorize. If you can memorize it in a week, then in two months you can memorize the whole Lotus Sutra." Well, it turned that I couldn't memorize the Lotus Sutra Dharani, so I couldn't memorize the whole scripture.

There have been many versions of the Record of Eminent Monks coming from the Liang, the T'ang, Sung, and the Ming dynasties. In these records, eminent monks are categorized according to their kinds of practice, one of which is reciting and upholding the scriptures. Practitioners who use Sutra chanting as a major practice usually choose one Sutra to chant, commonly the Avatamsaka Sutra or the Lotus Sutra. Master Fa-tsang (643-712), the Fourth Patriarch of the Hua-yen Sect (whose teachings are based on the Avatamsaka Sutra), sat in meditation one night and overheard someone next door recite all eighty volumes of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Each volume of this Sutra is ten thousand words long, but in a flash he heard the Sutra from beginning to end, and understood it with utmost clarity. It is impossible to recite the Avatamsaka Sutra in one day. In a day, you can only recite ten volumes, so the whole Sutra would take eight days. Yet Fa-tsang experienced the recitation in a very short period. In another story an ancient practitioner who had recited the Avatamsaka Sutra for many years had no need to beg for food, because deities and Dharma protectors looked after him and brought him what he needed. In yet another story from long ago a practitioner recited the Lotus Sutra a few thousand times. When he died, a lotus flower blossomed from the mouth of his corpse.

If you wish to practice the formal recitation of scripture in the Chinese manner, you must wash your hands and mouth and dress with decorum. There must be an altar with a Buddha image. You adorn the image and make offerings to the Buddhas of flowers, food, fruit, light and so forth. With such preparations, you can recite with utmost sincerity.

You begin with a mantra of purification of body, speech and mind, then an opening gatha, followed by the actual Sutra. You may have had wandering thoughts and missed some words of the Sutra. Afterwards, you recite the 'Mantra to Make Up For Mistakes'. Convenient, isn't it? You may have had wandering thoughts while doing the recitation, yet a mantra makes up for all the mistakes you made! Finally, you recite the gatha for the transferring of merits, so that the benefits of your recitation are transferred to all beings.

What of the posture in reciting Sutras? It depends on the length of the scripture. You may kneel or stand for shorter Sutras. In most Chinese monasteries, the morning and evening services, which last two hours, are done standing up. A whole-day recitation can be done kneeling or sitting, or alternating between the two. Sitting is either crosslegged on the floor, or on a chair. Kneeling is done by half-standing kneeling, so that one is not sitting on the heels. In the Chinese tradition, we usually adopt the half-standing position, while in the Japanese tradition practitioners usually sit on their heels.

The Japanese have special methods of scriptural recitation. They did not translate the Chinese scriptures into Japanese. Rather, they use the original Chinese characters, so reading the scriptures is quite involved. Alone, they recite the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters. This involves the reading and understanding of the scripture. In group practice, they also read phonetically, pronouncing the characters in Japanese to an accompaniment of drumming on the wooden fish. It follows that when the Japanese recite Sutras in Chinese it is like reading dharanis or mantras. They do not understand the meaning; they simply recite the sounds. This is difficult and praiseworthy, for the Sutras that they recite are often long. For instance, the Avatamsaka Sutra is eighty fascicles, the Parinirvana Sutra is thirty fascicles, and the great Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra is 600 fascicles. Their ardour in performing such difficult recitation is indeed praiseworthy.

The Japanese, however, also have a shortcut. Reciting the whole Sutra, character by character, is called 'true recitation'. As we have seen this is quite strenuous, so the Japanese have invented another kind of reading, which is called 'turning recitation'. Here the title of the scripture is recited once to represent each fascicle, while the pages of the scripture are turned. For example, for each of the eighty fascicles of the Avatamsaka Sutra, they recite, 'Homage to the Mahavaipulya Avatamsaka Sutra,' and flip through the pages!

When I was in Japan, I visited a monastery and the monks told me that they were going to recite the Avatamsaka Sutra that day. I was impressed, and said, "You're going to recite the Avatamsaka Sutra! How are you going to finish it?" They said, "No problem. We'll finish." This was before I found out how they were going to do it. Using this method, even the 600-fascicle Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra can be 'recited' in a short period of time. As far as I know, 'turning recitation' exists only in Japan, not in China.

In the Lotus Sutra we find a recitation with prostration practice. You recite the Sutra character by character, and after each word you perform a prostration and recite a phrase of homage to the Bodhisattvas who were in the assembly when the Sutra was delivered. Some practitioners in China recite the Diamond and Avatamsaka Sutras in this way. You must be thoroughly familiar with the scripture before you engage in this practice in order not to prostrate without understanding the words.

Sutras usually begin with 'Thus have I heard...' In Chinese this phrase is four characters, just as it is four words in English. So you would start by saying, 'Thus', and then you would prostrate to all the Bodhisattvas and the Buddhas associated with this scripture. For example, if you are practising the Lotus Sutra, you say, 'Thus,' and then prostrate while chanting aloud, 'Homage to the Lotus Sutra, Homage to the Assembly of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas present at the Lotus Sutra Assembly.' I have done this practice myself.

Some of you may be familiar with the Nichiren Sho-shu sect in Japan, which associates itself with the Lotus Sutra. They do not prostrate, but they recite the title of the Lotus Sutra. When you engage in this practice, do not recite or prostrate quickly. The idea is not to finish the scripture too soon.

In the Tibetan tradition, practitioners do the 'four uncommon preparatory practices', one of which is one-hundred-thousand prostrations. It doesn't take quite that many prostrations for the Lotus Sutra. There are only eighty thousand characters!

Now I would like to talk about six benefits derived from reading the scriptures. The Dharma is never fixed. Although I only mention a few benefits, there may be innumerable others, so please tell me if you think of any I may miss out.

First, by reading the scriptures we can realize mind, or 'illuminate the mind'. When we engage in Sutra recitation, we make use of the Sutra as a mirror to reflect back the reciting mind. This mind, prior to practice, is full of darkness and ignorance. We take the Sutra as a mirror by which we can model our behavior, until our minds fuse with the Sutra, and we directly realize the nature of our mind. I tell this to my monks and nuns in Taiwan but they refuse to understand. They ask, "Why don't you explain the Sutra first? Then it will be easier to read and memorize."

Second, Sutra reading can help us understand the meaning behind the Sutras. When I was a novice, I asked my master the meaning of the scriptures. All he said was, "Just keep reading, and you'll understand". Now I realise that complete familiarity with the Sutras naturally elicits the meaning.

Third, Sutra recitation can be samadhi or one-pointed concentration practice. I teach my disciples to use their ears to listen while they follow the chanting and not think about the meaning. One should use the mind to be fully aware of hearing as well as of one's own recitation. When you are alone, of course, you listen to your own voice reciting. But in group practice it is better to listen to other people's recitation. After all, one's own voice is really of no use, because you are unlikely to enter into samadhi by listening to it! How we enjoy listening to the sound of our own voices! Such attachment prevents us from entering samadhi. It is more helpful to do Sutra recitation in a group because then you can listen to others' voices in harmony.

A fourth benefit of Sutra recitation is the spreading of the Dharma. The Sixth Patriarch of Chan realized enlightenment upon hearing a layman recite a phrase from the Diamond Sutra: 'Let the mind arise without dwelling on anything'. In reciting Sutras do not be concerned with your own enlightenment. It is not important, so long as someone else achieves enlightenment.

Reciting Sutras can cause the ripening of another's virtuous karmic root. A non-Buddhist I know was travelling on a boat, feeling anxious and agitated. Next to him, a woman recited the Heart Sutra aloud. Since he had nothing better to do, he listened to her. After a while his mind became settled. That stimulated his interest. He thought, 'If just listening to scriptural recitation can benefit me, how much more will I benefit if I do the recitation myself.' He began to recite scriptures, and finally became a Buddhist.

The fifth benefit of scriptural recitation is the protection of Buddhadharma. The Mahayana scriptures say that whenever a person recites and upholds the sutras it is a manifestation of the Tathagata, the Buddha. Wherever there is recitation, there is the presence of the Buddha. Also, the Dharma-protectors and deities from the ten directions protect the people reciting and the area around them.

If we want to make Buddhadharma last in the world, it is not enough that the Sutras be present. We must recite and uphold the Sutras. If the scriptures exist, but no one recites and makes use of them, then they are just pieces of paper. They are very good for wiping pus, as Master Lin-chi said. But when they are recited and upheld, then they become Buddhist scriptures.

Sixth, Sutra recitation can be done to benefit the deceased. We can wish for their merit and virtue. Buddhists usually want Sutras to be recited for deceased family members. Some time ago, I had a Western student who placed great emphasis on seated meditation and practiced all the time. It happened that one of his close friends passed away, and he felt lost. He asked me what to do. I recommended that he recite Sutras as a way of transferring merit to his deceased friend. Now, you may ask, 'Is sitting meditation helpful for others?' It is helpful, but it is not as direct as Sutra recitation.

When a Sutra is recited, the power of Buddhadharma calls back the deceased so that he or she can benefit from listening to the Buddhadharma. If the deceased cannot come back, numerous sentient beings always gather when Sutras are recited, and it is they who benefit from listening to Buddhadharma. Because they benefit, the one who passed away also benefits.

The Brahmajala Sutra says that Bodhisattvas should explain the Mahayana Sutras and Vinaya for the sake of sentient beings whenever someone is seriously ill, and on the day when a family member, spiritual advisor or dharma master passes away. At the time of passing, and for three to seven weeks afterward, the practitioner should have a master expound the Sutras, and should himself recite sutras and make offerings, in order to benefit the deceased.

Finally, we recite the Sutras hoping to benefit sentient beings directly so that they generate Bodhi mind, the altruistic mind of enlightenment, and attain Buddhahood.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 1994 Sheng Yen Highlighted

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-120