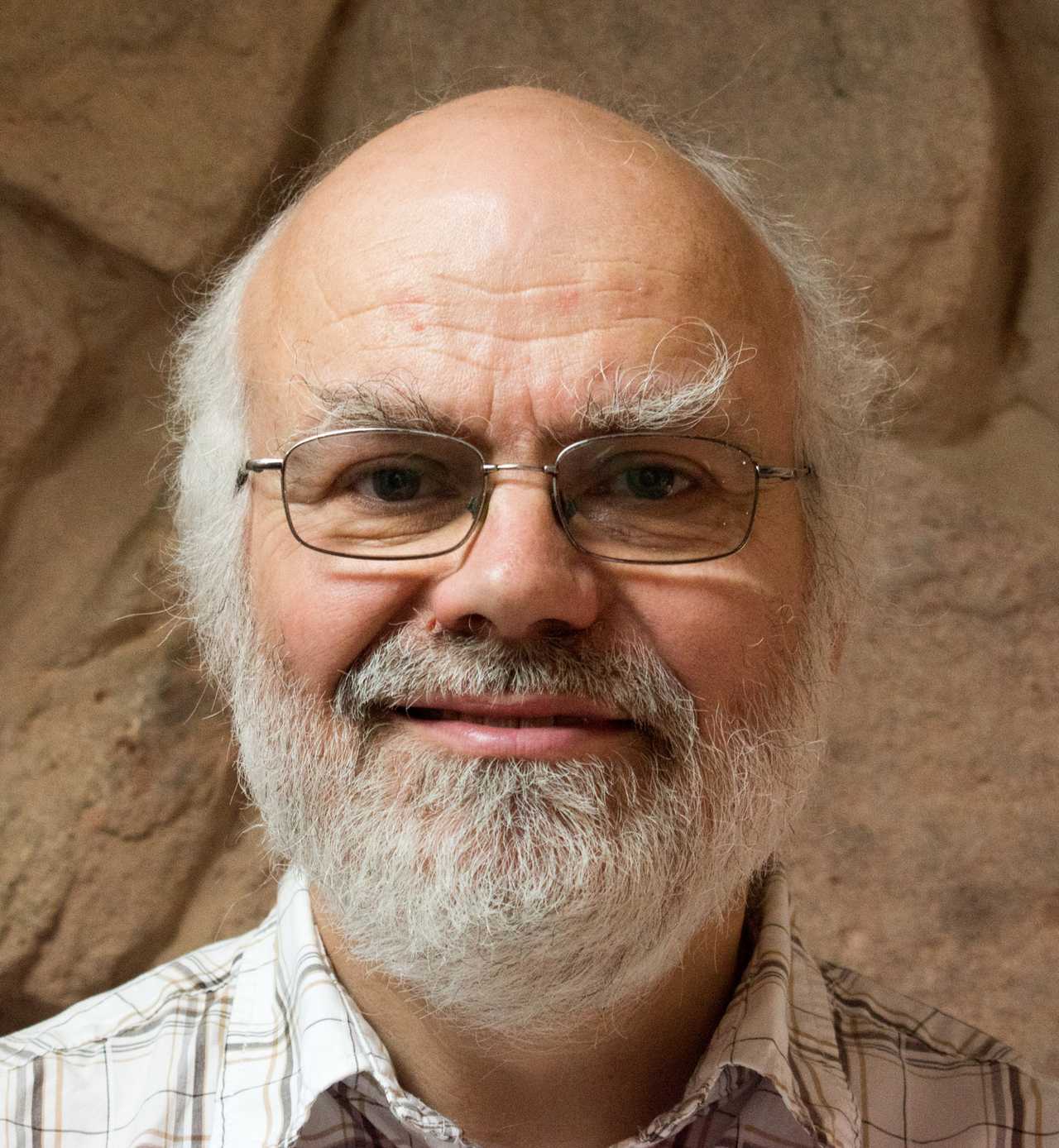

Ten Years On: Remembering Dr John Crook

Founding Teacher of the Western Chan Fellowship

On 17 July 2021, ten years after the death of John Hurrell Crook at the age of 80, the Western Chan Fellowship held a Zoom gathering to remember and celebrate this remarkable man and teacher. The following is an adaptation of a talk written by Simon Child for that gathering.

John had such a full and diverse life that it’s not possible for me to give his full biography this afternoon. I have to be quite selective, focusing primarily on his Buddhist life and career as it is relevant to our Fellowship which he founded in 1997 and for which he was the Founding Teacher.

I remember that one time in 2009 I was at John’s house. I think we had just returned from leading a retreat together in Poland. He passed me a slim red A4 booklet entitled A Tale of Two Houses1, saying, ‘You’ll need this one day to write my obituary!’ It was his writeup of his family history and his own early years, and of relevance to us today is the story which he sometimes told of an experience which was pivotal for him.

Early glimpses

It was during World War II and I think he would have been around 13 or 14 years old, living with his family in the New Forest, attending boarding school during the week. He was a self-taught bird-watcher who had no binoculars but who taught himself to identify just about any British bird by their song and by close observation of their behaviour. He was in the habit of exploring the woods alone or with his sister Didi when not at school. He wrote:

One day I was returning slowly home through a wood of tall beeches when a Grey Squirrel popped out of a hole in a tree trunk a few feet before me and sat still on a branch regarding me. I was immediately filled with an extraordinary joy so intense that everything seemed to spin and merge as I fell to the ground amazed and weeping, crying out spontaneous thanks to Christ for so beautiful a world; There was no thought in this, I seemed overcome by a moment of oneness with all things.

He described to me how he did not find anyone who could understand or explain to him what had happened – neither his parents nor school teachers nor local clergy. Yet eventually, as he read widely, he discovered that Buddhists not only knew and wrote about such experiences, they may also access them through their Buddhist practice.

This sparked his lifelong interest and engagement in Buddhism. Subsequently he had some other spontaneous shifts in consciousness, for example when seeing red kites circling at Maenllwyd. Some of these experiences were confirmed in 1989 by Chan Master Shengyen as ‘seeing the nature’, the so-called enlightenment experience.

Army National Service: first contact with Buddhism

During the Korean war in the early 1950s John was called up for army national service. Being a recent university graduate he was sent to officer training then posted to supervise a defensive gun battery on a hillside overlooking Kowloon Bay in Hong Kong. I don’t think his gun battery ever fired shots in anger but he described with a smile how their training shots sometimes went rather too close to junks sailing in the bay!

Before setting sail on the troopship to Hong Kong he decided to educate himself in the culture of the land to which he was heading, and during the voyage he read Christmas Humphreys’ book on Buddhism.2 During his spare time in Hong Kong he would often visit temples and monasteries. He also attended a series of teachings on Chan Buddhism given by a lay teacher, a student of Chan patriarch Xuyun, who was kind enough to translate his teaching solely for the benefit of John who was the only non-Chinese speaker attending. As John put it himself in his book Hilltops of the Hong Kong Moon,3 which chronicles some of his exploits in Hong Kong, Buddhist study and exploration was not the way that most soldiers spent their free time, but that is what John did!

Following his national service John went to Cambridge to study for his PhD. During his time there he was secretary of the Cambridge University Buddhist Society. One talk hosted by him during his time there was by the same Christmas Humphreys whose book he had read on the way to Hong Kong. Following his PhD, John’s career took off. So far as I am aware he did not have much involvement with Buddhism during those early years of his academic career. I imagine he was preoccupied with his work.

The Personal Growth Movement

In the late 1960s / early 1970s he spent two years on a Fellowship at Stanford University in California, and during that time he became involved in the ‘experimental psychology’ and personal growth movements, including events such as Encounter Groups. I think it was this that triggered him to take up the practice of meditation. Following his return from Stanford he visited Samye-Ling Tibetan Buddhist centre in southern Scotland and it was there that he was introduced to meditation practice. He also attended retreats at Throssel Hole Buddhist Priory (as it was then called) in Northumberland to practise Soto Zen under the teacher Roshi Jiyu Kennett, an English woman who had trained in Japan.

So John already had Chinese Chan influences, from his lay teacher and explorations in Hong Kong, and he subsequently gained both Tibetan and Japanese Zen Buddhist influences. Furthermore, he continued his experimental psychology interest, training in the ‘Enlightenment Intensive’ process and establishing the Bristol Encounter Centre in his home city of Bristol. Looking for a base for these activities led him to seek out and buy Maenllwyd, a rather derelict farmhouse on a Welsh hillside. He held encounter group activities there, and in 1975 he also held his first Western Zen Retreat, which was his fusion of the Enlightenment Intensive process with the structure of a traditional silent Zen retreat.

I was a medical student in Bristol 1975–1980. In 1976/7 a student society I was involved with was looking for someone to run some group exercises and I was recommended to ask John Crook whether the Bristol Encounter Centre could help us out. I ended up talking to him about this in his office at his home in Alma Road Bristol, and I remember noticing the Buddhist artefacts there and being a bit curious about them. My society did get to have our group activities, but it was a different member of the Encounter Centre who ran those for us, not John.

Beginning to teach and lead retreats

By chance in 1978 I heard a talk about meditation and became interested in it, and later in the same series of talks John spoke about his Western Zen Retreat. It was January 1981 when I first attended a Western Zen Retreat, led by John at the Maenllwyd. In several ways I was hesitant and unsure about the venture when I arrived, but John’s energetic and committed leadership carried me through and I subsequently returned again and again, finding the practice very effective for me and appreciating John’s insight, his energy, and his skills in running the events.

John’s approach to his own practice and his teaching was quite eclectic, and alongside the Western Zen retreats he also ran other retreats such as Soto style sitting, and also invited other teachers to the Maenllwyd such as Geshe Damcho Yonten.

At that time he was a self-appointed teacher with no formal authorisation for what he was doing. In those days that was common and not an issue for any of us as we were happy with what he was doing. But it did have some drawbacks – for example he found that the Buddhist Society in London would not recognise him. He had wondered about making a proper connection with a more formally recognised teacher.

Chan Master Shengyen and Dharma transmission

John had continued to make occasional visits to his original lay teacher in Hong Kong, Mr Yen Shiliang, who had subsequently been ordained and become the monk Yan Wai Fashi. On a visit in the mid-1980s John found Yan Wai Fashi in hospital and it was apparent that he had become too old and deaf to continue teaching. When John left the hospital he browsed the Buddhist bookshop across the road and found only one book in English. It was Getting the Buddha Mind, by a Chan Master called Shengyen who taught in New York as well as in Taiwan.

It occurred to John that attending teachings and retreats in New York would be easier than travelling to Hong Kong, and from 1986 he practised regularly on retreats in New York with Master Shengyen. John published his collection of retreat reports from these retreats in New Chan Forum and these are available for you to read in issue 20 (1999).4 John also persuaded Master Shengyen to travel to UK and lead retreats at Maenllwyd in 1989, 1992, and 1995, and at Gaia house in 2000.

On one of those retreats in New York, in 1993, Shifu Shengyen greatly surprised John by formally transmitting the Dharma to him, thereby making him a fully authorised independent Chan teacher, a direct descendant in the Chan lineage. This was a very significant event and he took the responsibility very seriously indeed. It invigorated his Chan teaching and led to further developments.

Following the retreat at Maenllwyd with Master Shengyen in 1989 some of the participants wanted to continue practising together. Since they all lived in or around Bristol they formed the Bristol Chan Group. They also started publishing New Chan Forum.

Western Chan Fellowship

Soon after his transmission in 1993 John set in motion meetings to investigate the creation of a national Chan institution, as a vehicle to continue spreading Chan Dharma beyond his own lifespan. In 1997 the Western Chan Fellowship was established with a carefully considered constitution and was registered as a charity.

John continued teaching actively right up until his sudden death in July 2011. For example, he and I led a retreat together in Poland in May 2011 despite the back pain and mobility problems he was then experiencing. But he did make a deliberate choice to lead fewer retreats during what turned out to be his last few years, because he wanted to devote time to researching and writing his last book, World Crisis and Buddhist Humanism, which was published in 2009. He was able to make that choice because under his teaching and supervision the WCF had gained several additional retreat leaders, not only myself but also Hilary, Jake, Fiona and Eddy.

Other sides to John

Inevitably given the time constraints, this has had to be a rather sketchy and primarily factual description of John’s Buddhist career. I feel I have not adequately conveyed his overall breadth and depth, so let me conclude by giving you a glimpse of a few more of the many facets of John Crook.

He was an adventurer and an explorer and he several times undertook trips to the Himalayas, and other places such as India and China. Sometimes these trips were pilgrimages, perhaps just with a travelling companion or maybe leading groups of interested people. Sometimes the expeditions were primarily for academic field research such as for his contribution to research on the anthropology of Ladakh, but even then they usually included an element of pilgrimage and Buddhist research as he sought out remote monasteries and caves occupied by solitary yogins.

He had an eclectic approach to Buddhism, exploring and practising and drawing his teaching from multiple traditions, especially Chan, Zen, and Tibetan Buddhism. He was also influenced by other teachers such as Krishnamurti. He coined a phrase, ‘Open Buddhism’, indicating that he was open to practitioners moving around different teachers and traditions and he did not require students to commit to him personally as is common in some Buddhist traditions.

He was an academic in the psychology department at Bristol University, where he was Reader in Ethology, the study of animal behaviour. Some of his original research was significant and well-regarded, and a recent book5 credited John as the ‘founding father of socio-ecology’.

John once told me that his colleagues at the university said that until he went to Stanford University in the late 1960s he was a proper academic scientist, but when he returned with an interest in such things as encounter groups, meditation, and even Buddhism, he was seen as having gone a bit soft in the head! This of course was told with a laugh as John liked to tell stories against himself. But probably it’s true that there was a change in him as it was from this time onwards that he became much more involved in Buddhist practice and teaching.

Many of the early participants in his encounter groups and Buddhist retreats heard about these events through their contact with him at Bristol University, and so naturally the participants were often fellow academics and students of Bristol University. This in large part explains the SW England bias of early WCF membership. Yet it also explains the wide geographical dispersion of WCF membership as of course many students, including myself, do not settle in the region of their undergraduate studies but either return to their hometowns or follow job opportunities anywhere in the country or elsewhere in the world.

Perhaps as a result of his boarding school and army officer training – or perhaps it was naturally John! – he carried an air of authority and decisiveness. He also loved to experiment – whenever he heard of something that appealed to him, such as a new approach to meditation or to teaching, he would say ‘Let’s try it out!’

He was a raconteur and poet and writer. He loved telling stories during his Dharma talks; in fact he loved telling stories at any opportunity!

He often wrote poetry, and some of this was published from time to time in New Chan Forum. Following his death his son Stamati collected John’s poems into a volume entitled Letting Go, available as a printed book or as a free ebook.6

For a long time I managed the production of New Chan Forum. Typically I might remind John that we were due for an issue, and he might respond that he didn’t have much material but would see what he could do. Four to five days later I would receive an email attachment containing a whole issue of NCF which contained various pieces already submitted by other people plus three to four long and varied articles written by John at high speed especially for that issue. Stamati also collected John’s very many writings for New Chan Forum into a thick compendium called Circling Birds.7

John’s writings extended well beyond New Chan Forum. He continued to write and present psychological papers even after his retirement, and for many years he was an occasional writer of book reviews for The Times Literary Supplement. He also published several books in his own name and was a contributor of chapters to several others.

He was very interested in the human condition, and in the condition of individual humans. He was very concerned to help people find their way out of their suffering. This was perhaps most obvious in his careful and penetrating retreat interviews, much appreciated by many of us present today, but also more generally in his care for the authenticity of Dharma teaching and its continuation. It seems almost trite to say it, but as a direct lineage descendant of the Buddha his concern for helping others to address their suffering was completely appropriate and in accordance with the Buddhist tradition, and we have all benefited from it.

To follow, let’s hear from John himself. Overleaf is a transcript of a Dharma talk given by John on the second day of a Western Zen retreat in 1988.

Notes

- A Tale of Two Houses can be read online at http://johnhurrellcrook.com

- Christmas Humphreys, Buddhism, Pelican Books 1951

- Hilltops of the Hong Kong Moon can be read online at http://johnhurrellcrook.com

- Working with a Master (from New Chan Forum 20)

- Tim Clutton-Brock, Mammal Societies, May 2016 Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1-119- 09532-3

- See https://www.lulu.com/search?contributor=John+Hurrell+Crook or http://www.johnhurrellcrook.com/

- See https://www.lulu.com/search?contributor=John+Hurrell+Crook or http://www.johnhurrellcrook.com/

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2021 Other Articles Simon Child

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-572