The Circling Birds: Openings to Insight on the Path of Chan

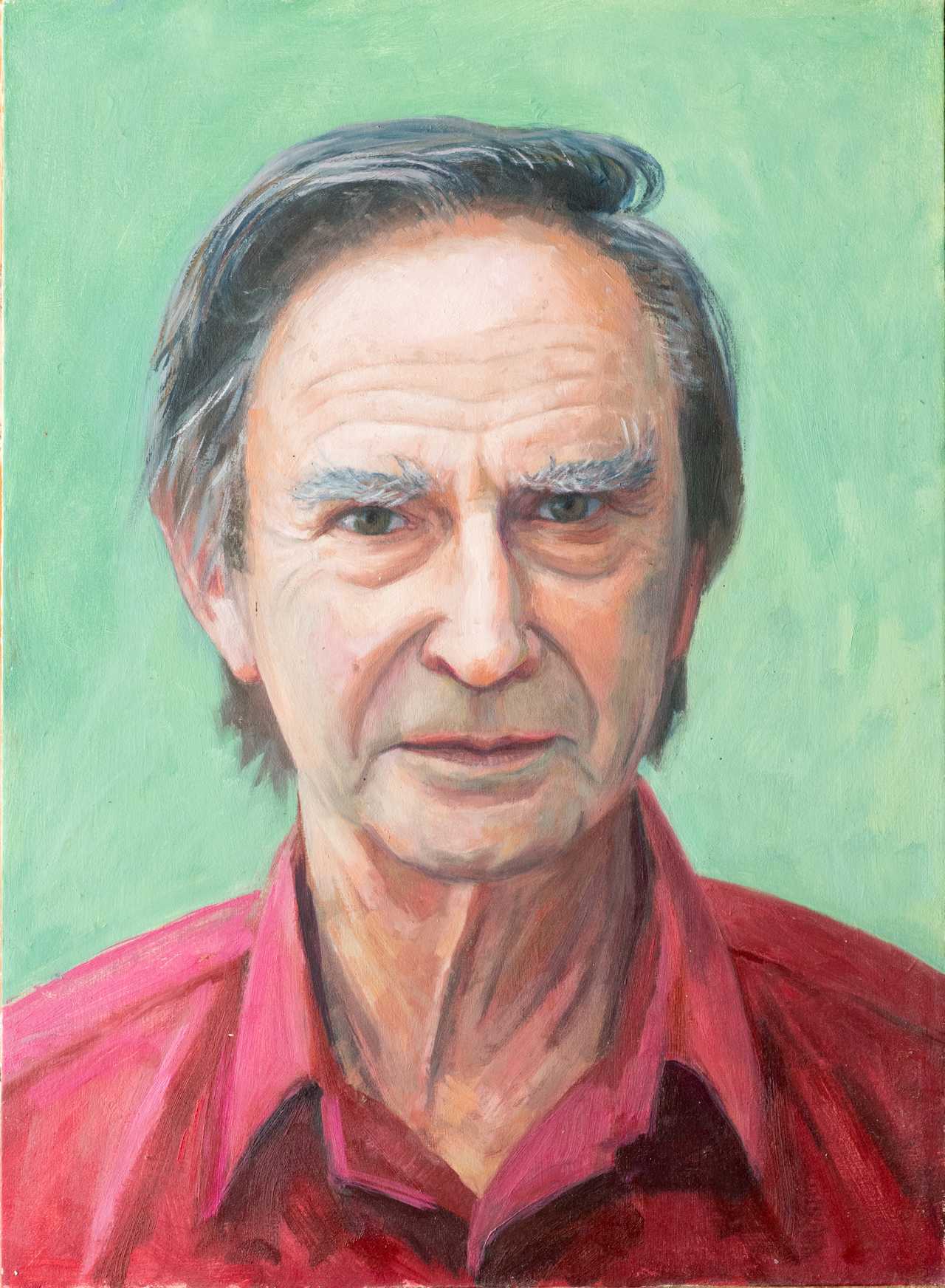

In Chan Comes West, Master Sheng Yen’s five lay Dharma heirs share their stories on the path, including how they came to the practice, their inner struggles along the path, and what receiving Dharma transmission has meant for them. It is hoped that readers will find these stories inspiring and be encouraged to make great vows in their own practice. Here is John Crook’s chapter from that book, which was reprinted in Chan Magazine Summer 2017.

Edited by Rebecca Li with editorial assistance from Ernie Heau. British conventions of spelling have been preserved, though American style punctuation is used.

Early Years

Once upon a time, and a very long time ago it seems too, I was a teenager living in a forest in southern England. World War II was raging. My hometown, the port of Southampton, had been devastated by German air raids. My father was in charge of the “Air Raid Precautions” section of the Civil Defence in a district near the docks. Among other things, he walked through railway tunnels at night with a torch looking for unexploded bombs. In 1940 the family, except for Dad, had moved out into the New Forest for safety. England is an old country and the forest was first “new” in the twelfth century when the king had set it apart for hunting. We were all expecting a Nazi invasion even though things seemed to go on more or less as usual while the RAF shot the German planes out of the sky above our heads. The Battle of Britain was at its height. My Dad wrote to me at boarding school. “Whatever happens,” he said, “Never forget these words – NIL DESPERANDUM.”1 I suppose that was my first mantra.

As the war gradually went our way, I explored the beautiful forest and the moorlands around our home. I had become a small but ardent bird watcher. Since I had no binoculars, I had to move very quietly among the trees and undergrowth. I learnt solitary field craft the hard way and an ability to still the mind in focussed attention undoubtedly developed at that time. One day I saw a squirrel pop out of a hole in a great beech tree. It looked at me from a few yards away and we gazed, motionless, at each other. Suddenly I was overcome by an extraordinary joy, all my concerns seemed to disappear and I found myself fallen to the ground uttering words of thanks to Jesus, tears falling from my face. That experience became a turning moment for my whole life: I had come across something that was altogether “other.”

I went to school and studied biology, learning about Darwin, evolution, physiology and physics. A deep suspicion arose as I did so. All the truths of my childhood Christianity seemed untenable before this fascinating new knowledge which eventually led to my career in biology and anthropology.

Scepticism was not new to me. When I was very small, my sister and I were visited every Christmas by Father Christmas, who came down the chimney and filled our socks with goodies. I began to suspect this was a bit of fun for my parents but I did not want to disclose my doubts because then of course I wouldn’t get the presents. All I learnt from their kindness was a sort of deviousness. I continued to harbour doubts and feel oddly guilty until one year they forgot all about it. Later, at school, it seemed to me that Jesus, God and all that lot were just further examples of Father Christmas. What humbug! I thought; but how sad that these beautiful ideas had to be dismissed as no more than nonsense intended to keep us happy.

My late adolescence was not a happy time. Again and again I was struck by feelings of futility in life and a personal emptiness. I needed to find some anchorage in a world that had become meaningless. But then I remembered the squirrel, the beech tree and that extraordinary moment. So there is something else, I thought, and it cannot be explained away. I had touched it through my own awareness.

The Quest

I read widely and discovered that there were such things as mystical experiences. I thought I knew exactly what that meant because I had had a firsthand experience myself. But I failed to find anyone else who had known what I had known. As a university student I went to lectures by priests. Sooner or later the word God would inevitably arise. I would put up my hand. “Excuse me,” I would say, “You have just used the word ‘God.’ What does it mean? Without a definition I cannot see how your argument follows.” Never did I get a reasoned reply. I must have been an insufferable student.

Reading Plato, especially The Symposium, began to offer me some helpful perspectives. From a love of small things one could grow to understand absolute beauty itself. Perhaps that was what I needed to comprehend, I pondered. I had been sent to a British public school, all male, firm discipline, a lot of sports especially rugby football which I came to love, good academic class work and military training. I hid the pain of separation from parents and home from both others and myself. On Sundays I would gaze along the railway lines and count the days. British public schools in those days taught one how to cope with a special sort of existential doom in which we all participated. Lonely boys, gradually finding in each other the meaning of friendship, had problems with emotional understanding, their sense of loss and family betrayal, and the storms of sudden love. Yet it stood one in good stead when enrolled into the army for National Service.

Hong Kong

It was the time of the Korean War and I reached the giddy rank of Second Lieutenant within a year. Soon I was on a troopship, an artillery officer specialising in radar, bound for Hong Kong. On the way across the rolling wastes of the Indian Ocean I read Christmas Humphreys’ book Buddhism: An Introduction and Guide. I found that here there seemed to be some themes I could not instantly rubbish through the reductionist scepticism of which I had become not a little proud. In Hong Kong, I sought out Chinese friends, which was an adventure in itself, and finally I was introduced to a Mr. Yen Shiliang, a merchant who had “sat” with the great Master Xuyun. He welcomed me to his evening classes held once a week in a traditional Chinese doctor’s surgery.

Of my meetings with Mr. Yen I have written: “Here I am up against a very different interlocutor. I can argue with ability and precision, the premises and inferences tidily related, and Mr. Yen will follow me, give a partial answer along the same lines and then suddenly, with a look and a few deft phrases of equally clear reasoning, he sweeps all my contribution to one side. Lo and behold, the conversation has entered another dimension, still the same subject, still logical, yet in a realm in which only he is master and in which I can only hover along behind trying to follow his fluent discourse and the extending reach of his mind. It is all very good for me!”2

What is new for me is the way he calls on the intuitive as well as the intellectual intelligence. It is this which gives his words such added power and makes them fly. These Buddhist ideas do not rest on logical reasoning alone. Reason only “circles about and about forever more,” bringing us back in through the door through which we went. He seems to speak justly when he says, “One either knows or one does not.” So far this knowing is however only within his dimension not mine. It is as if he suddenly uses an entirely fresh verbal ‘conjugation’ which shifts the whole context of a conversation into another register.”3

Soon I found myself exploring the world of Chinese monasteries. On first visiting Baolin Si (Precious Woods Monastery) on Lantau Island we had to pass a small stone gateway. “On rounding a shoulder of the mountain and approaching the high point of a col, we came across a great stone arch silhouetted nakedly against the darkening sky. Solitarily placed among rocks and scree near the top of the pass, it gave the location a powerful atmosphere. Coming close we could see it was painted white and that there were great black Chinese characters incised upon it. We stood below it listening to the wind and gazed up, puzzled, at the writing. Then, to my surprise, we found near the bottom of one column an inscription in English. Three terse phrases lay one above the other:

To the great monk Sing Wai

There is no time

What is memory?

The words were so unusual, so unexpected, that on reading them I was shocked. There was a momentary gap in my thinking and feeling as I tried to fathom their paradoxical power. This was my first confrontation with a text that summarised Chinese Buddhist insight and the question it asked not only perplexed me deeply but was to go on rankling under the cover of my daily activities for months to come. It came as a revelation to realise that here was a perspective that asked the very questions that seemed to have been deliberately avoided in my religious education, questions which in recent years had concerned me more and more and would not go away. A sudden silence was filled with the sound of the light wind and below the mists parted to give a momentary glimpse of a small junk heading out to sea.

Later, near the end of that first visit, I found one room off the courtyard that particularly intrigued me. “It seemed to be a kind of small hall or study, for there were hassocks on the floor and, around the walls, ran a stone pew upon which, at intervals, cushions were placed. As I passed the window I noticed what appeared to be a life-sized image sitting just out of the light coming in from the window. I looked more closely and realised that it was in fact a young monk. He was sitting with his legs crossed, the soles of the feet upturned upon his thighs and his hands resting together lightly between them. His back was upright but not rigid and his head inclined slightly forwards. His eyes were shut and his face completely relaxed, expressionless, serene. I watched him closely, strangely drawn to him with an emotion akin to awe. His breathing came and went so slowly, so slightly, that he seemed not to move at all. The Buddha posture gave him an air of detachment, of distance, of separateness from the world of men, from life even. He seemed most like the mountain itself filled with an impersonal, unengaged, power meditating upon its own centre. The words on the gate came back to me, ‘There is no time. What is memory?’ What indeed could memory be without time? What could time be without memory? What was memory? What was time? Was this the way to find the value of emptiness within the vessel? The questions spun in my mind and I pondered over them near the window for some time before I drew myself away.”4

Leaving the mountain that day to return to the rigours of the army camp: “As the clouds drifted alone and serene over the hills my eyes followed them; I felt that everything in my life and in the world around me had fallen still; that it had always been so; that nothing had ever happened nor would happen and that it would be thus from everlasting to everlasting.”

Searching Among Teachers

These experiences became the foundation for my life-long love of Buddhism and especially for Chan. As the years rolled by, I explored many themes with a number of great teachers. There was but little Zen in the West after the Korean War, and I began by following Mr. Yen’s advice to meet Krishnamurti. Years later, I lived in Poona and was able to attend a small weekly class with him. I still regard him as a great bodhisattva and from him I learned much, although the brahminical social background to his teachings seemed to keep some aspects of his life remote and mysterious. Later I began to “sit,” teaching myself meditation first at Samyeling Tibetan Centre in Scotland founded by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and then receiving instruction and interviews of great value with the monks at Throssel Hole Priory in Northumberland. One retreat was led by Roshi Jiyu Kennet. In an interview she remarked on the erratic nature of my practice. “One two three four five,” she said “Not one eight three two five!” There was something so total about the way she prostrated before the Buddha that it brought tears to my eyes. I began to understand that wordless teaching could be the most profound.

The teacher I came to love most, even though my contact with him was slight, was Lama Thubten Yeshe. I had attended many Tibetan retreats and taken a number of higher initiations.5 In Italy the lama was teaching the Five Yogas of Naropa. Really we only got as far as an introduction to Tumo but it was the lama himself who fascinated me. He would go into meditation in front of a huge audience and somehow I felt drawn deeply into a most profound silence. He had a rare almost magical charisma and a way with Westerners that I have never seen equalled in an Asian teacher. From him and other Tibetans I learnt the power of mantra and certain tantric practices that remain a profound resource to which I turn in times of distress.6

Eventually, I decided I would like to renew acquaintance with my original love, Chan, in Hong Kong. I returned there and met my old teacher. By the 1980s he was very old and extremely deaf and, although I had some wonderful conversations with him, it became clear I needed a further teacher. In a Hong Kong Buddhist bookshop I came across just one English book, Getting the Buddha Mind, by Master Sheng Yen. When I read this, I knew I should cross the Atlantic and sit with him in New York. This was important because I was already leading Western Zen Retreats in the UK7 and felt the need for support from someone who knew so much more than I.

Transmission

I have sat many retreats with Master Sheng Yen and I have written up my retreat reports into an article “Working with a Master.”8 Shifu has become what the Tibetans call my “root teacher.” It is difficult to describe what I owe to him. “Everything,” I might say, but perhaps the most important thing has been the growth of Dharma Confidence. Without his faith in me, which I feel I can never justify, I could not now do the work of Dharma that I do.

During my life I have had several experiences of which the meeting with the squirrel was the first. When Shifu came to England for the first time, I decided to ask him about those experiences. Intuitively I already knew what they were but I needed the response of a master.

“With a mind quietened by meditation I felt free to review my life in the Dharma and I resolved to tell Shifu of those rare experiences which had appeared as if by grace several times in my life since boyhood and which I have always been reluctant to share with anyone because of their incomprehensible nature.

I gave him a straightforward account of one event that had followed a retreat at the Maenllwyd, Wales. I had been down the lane on the point of departure and had returned from the car on foot to a gate which I had forgotten to close behind me. As I swung the gate, I saw two Red Kites wheeling overhead in the frost-clear air of the sunny, winter day. Red Kites I had never seen near the Maenllwyd before so I exclaimed to myself with joy “Oh look at that!” As I gazed at the circling birds my mind suddenly fell empty, I was no longer present within “my” experiencing. There was only the landscape and the circling birds, a sense of wonder and amazement. I stood gazing for about twenty minutes as the birds gradually withdrew and I felt the experience slowly fading as thought reappeared and “I” returned to “myself.” This was a reawakening, a joy to have found “it” again, for such an experience has only rarely appeared, often with years between.

I also told Shifu of another occasion when I was visiting Naropa’s cave at Dzongkhul Gompa, in northern India. With three companions, I had spent three days in July 1977, crossing the immense ice fields of the 18,000-foot Umasi-la pass through the Himalayas into the Zanskar valley of Ladakh. As we were being given tea in the upper hall of the little monastery I had glanced out of the window. The mountain side opposite was falling away as ice-laden water rushed down in a massive waterfall from the glacier above. Again emptiness of self came over me and the great space of the mountains seemed to fill me with itself. I wandered alone for half an hour up and down the flat monastery roof until I felt myself again gradually returning as thought once more created self-concern.9

I asked Shifu what, from the point of view of Chan, was the meaning of these experiences. Without hesitation he told me that this was “seeing the nature” (Japanese kensho). I was overjoyed to receive his confirmation of what I had suspected but never been able to test in a direct meeting with a Zen master. Shifu also said that, from what he knew of me, he had already understood that I had had such experiences. He then said “Congratulations,” and told me to make three prostrations before him, which I did with profound feelings of awe, joy and liberation. He also said that from now on he wanted me to run Chan retreats with his blessing and, as it were, as his representative.10

While I experienced a great freedom, I also perceived immediately the responsibilities that this recognition implied for me. I also felt bewildered, for what did congratulations have to do with simply experiencing the most basic nature of myself? I felt an odd shyness too for, while I was happy at Shifu’s recognition, I did not want anyone else to know. In sharing with others minefields of potential miscommunication loomed before me.”

Later, after I had sat further with Shifu and had run several retreats in the manner taught by him, I went to New York for further training in May 1993. Without any consultation, Shifu told me he was going to give me transmission, thereby confirming me as his second Dharma heir in the Linji tradition descended from ancient times through Master Xuyun. I was really surprised by this, for I was not Chinese, I was not a monk, I was not a speaker of Chinese languages nor could I read characters. Furthermore I knew my own vexations, neuroticisms if you like, only too well. There are many samskaras in my personal life, some of them very painful and difficult. I was sometimes subject to considerable depression. I felt totally unworthy. Yet I also had faith in Shifu. If this was what he wished me to do, then I would try to fulfil his trust.

After he had passed the transmission to me, Shifu gave a most useful talk to the assembly. In it he explained exactly what was essential for transmission. Shifu said: “We should be joyful because we can witness today that Buddhadharma is something alive. Despite these changing times it is not something that has died, but continues and with vigour. When such Dharma lineage might be passed to any one of us – that, nobody knows. As practitioners we do not seek to attain or gain anything. We do not seek the affirmation of others; a lot of conditions are necessary. Firstly you must have the correct understanding of the principles of the Dharma. Secondly, you must have your own experience of practice. Thirdly the right conditions must exist in space and time; the circumstances must be appropriate. Fourthly, help must be given to all people wishing to learn. Without all of these conditions being fulfilled, then even if the lineage were to be passed on to you, the transmission would not be fulfilled.”11

Shifu later made his meaning precise. For a transmission to be fulfilled there must be people wishing to receive teachings; the teacher must know how to teach and have a place in which to do it. Some constancy in the teacher-student relationship needs to be established. He had seen my work in running retreats at the Maenllwyd, and this formed the basis for his decision in my case. Shifu has made clear that while an experience of kensho is required for transmission as a Dharma Heir, it is not completely essential for those wishing to teach. There are times when a Dharma descendant of a master may not be available. Nevertheless, one who has not experienced kensho and had it confirmed, cannot evaluate such an experience in another, and this is essential to the transmission of lineage.

In private, Shifu told me that there was nothing to be proud about in these matters. Everyone has his or her inadequacies, so that any pride would cause a downfall. Furthermore, he remarked, at any previous period in Chinese history, when there were great teachers around, I could not have received any recognition at all. Only in the present era, when, in spite of superficial brilliance, the darkness of the mind is so thick, is it possible for those with attainments as thin as my own to be considered valuable, indeed essential as teachers.

I was deeply touched by the radical nature of Shifu’s action. In passing transmission to me he was putting his own reputation on the line. I was amazed that he should consider me worthy to carry this task back to Britain and Europe. Yet his faith in me gave me a feeling of certainty that this was indeed what I wanted to do and I determined to do it to the best of my ability – in spite of vexations, self doubt, periods of depression and a certainty of my basic unworthiness. I found the extent of his trust remarkable. When I asked him how I should teach Chan in Britain, he simply said, “I am Chinese. You are British. That is something for you to find out!”

Shifu tells the story of his own doubts before coming to America to teach. He had told his teacher he was concerned because he knew no English. “Bah!” his teacher had said, “Do you think Zen is taught by language?” I felt that Zen concerns itself with matters of the human heart wherever that may be. We are all at a base level very much alike irrespective of our cultures and histories. While we need to understand the cultural background to the forms of Buddhism and the complex relations between thought and experience, in the end it is heart teaching that makes a difference.

Teaching

In recent years, while continuing to train in Chan, I have worked together with my colleagues in England to create and develop the charitable foundation of the Western Chan Fellowship, taking great care to provide in its constitution the rights of its members to criticise the teacher and even dismiss him or her if required. I have also favoured critical discussion of teachers’ and practitioners’ ethics as a modern way to understand the precepts. There have been terrible failures in the transmission of Zen in the West. Both the sanghas to whom I teach in continental Europe came to Chan after disasters with immoral and unethical teachers. These scandals have been a source of deep distress for many and I have had to try to heal such wounds.

I have also worked hard to understand the problems of lay Zen in the West. Few of those interested in Zen/Chan are likely to become monks. It is a lay practice that has to be developed here. Links with Western thought, science, and psychotherapy are all important as also is the paradoxical relationship with Western capitalism itself and the ruination of world ecology that is resulting from it. In common with a number of mostly American scholars, I believe that the excessive interest in enlightenment “experiences” generated by the one-sided approach of the great Dr. Daisetz Suzuki has been based in the highly individualistic nature of the Western self. This has given an odd twist to Western Zen, making it almost competitive. Who has had the deepest experiences? Who has the best Master? These are seriously faulty paths.

I am beginning to see that we Westerners need a different emphasis from that generated by Dr. Suzuki. In brief, we need to seek wisdom more than enlightenment and to get to know the presence of enlightenment as a basis to our lives – a form of knowing rather than short-lived ecstasies. I mean that, although enlightenment experiences provide the opening insights of Dharma, few of us can attain them – simply because the natural egotism of the average Westerner gets in the way. Such experiences cannot be attained through desire or any kind of wanting. Usually they crop up almost accidentally, or when one is surprised while in a highly focused state and the ego happens to have dropped its guard. It seems clear that one cannot train directly for such an experience. One can however train in wisdom. Meditation practice, retreat experiences, self confrontation and encounters with teachers, the problems of life and our quest to manage ourselves all yield wisdom if one cultivates mindfulness of their meanings. Silent illumination is, I believe, an exceptionally useful method for Westerners devoted to the path and for cultivating a quieter, better balanced approach to “seeing the nature” than more dramatic ways. In such a context, kensho may or may not arise. Such an experience may be life changing but there are other ways too. Whether or not one can cultivate selfless kindness and compassion is what matters. Whether one can manage one’s life wisely, that also matters. Whether such understanding can be used in wise judgements in worldly affairs, that too is what matters. Can we train to bring about a difference? I do believe so; not by meditating in thousands in the trouble spots of the world. That is mere superstition; but in our own hearts, our own relationships and our own communities.

One day I was discussing advanced practices with a Tibetan geshe. We were very enthusiastic and getting carried away by exciting topics. Suddenly he stopped and looked at me, “John,” he said, “when were you last kind?” Here was a fine teacher bringing his interlocutor back to earth, to the nitty-gritty of our hearts’ failings. Yes, wisdom first. Maybe enlightenment may follow. Maybe not.

A few words in another register, a perspective on sitting Chan, to conclude:

Silence in my head

sweet sunshine and the jackdaws calling,

dew on the autumnal grass

muddy puddles and fallen leaves

scarlet on the lawn.

Silence in my head

nothing doing there,

the morning hour, mists dissolve

in grey-green hills, the rocks

show through the soil.

In the silence of the world

nothing ever moves

the wind-drift stillnesses

the circling birds.

John Crook October 2001

References

- It means “Never despair!”

- Paragraphs within quotation marks are quotations from diaries or other published materials by the author as quoted.

- Quotation from: John H. Crook, Hilltops of the Hong Kong Moon (London: Minerva Press, 1997).

- Ibid. Chapter 8.

- Two forms of Avalokiteshvara with Ratung Rinpoche and the Dalai Lama, Heruka with Lama Thubten Yeshe, Kalacakra with the Dalai Lama, Padmasambhava, Vajrasattva and some Dzogchen yogas from Lama Dudjom Rinpoche, Yamantaka, Red Tara and an introduction to Powa from Chagdrug Rinpoche. I was given a rare Mahamudra text of Tipun Padma Chogyal from Khamtag Rinpoche while in the field in Ladakh.

- For detail concerning my work in Tibetan Buddhism see John H. Crook and James Low, The Yogins of Ladakh: A Pilgrimage Among the Hermits of the Buddhist Himalayas (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1997).

- In the late 1960s I had been a fellow at the Centre for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, a think tank of Stanford University. While there I became acquainted with the Esalen approach to encounter groups, sensitivity training, gestalt psychotherapy, etc. On my return to Bristol my students asked me to present these new methods to them and this led finally to the creating of the Bristol Encounter Centre in the city. The Western Zen Retreat originated and was developed from my work with Jeff Love who was then presenting the “Enlightenment Intensives” of Charles Berner in Britain.

- This article is presented as Part 3 in the book: Master Sheng Yen and John Crook, Illuminating Silence: The Practice of Chinese Zen (London: Watkins, 2002).

- For a fuller description see Ibid. 6, 37–40.

- See John Crook, Catching a Feather on a Fan: A Zen Retreat with Master Sheng Yen (Shaftesbury, Dorset, UK: Element Books, 1991) 104. Also see further in Ibid. 8.

- The text of this talk was recorded and published in New Chan Forum 9, Winter 1994, 2–5.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: For Newcomers 2011 Other Articles John Crook

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-556