The Illusion of Separateness

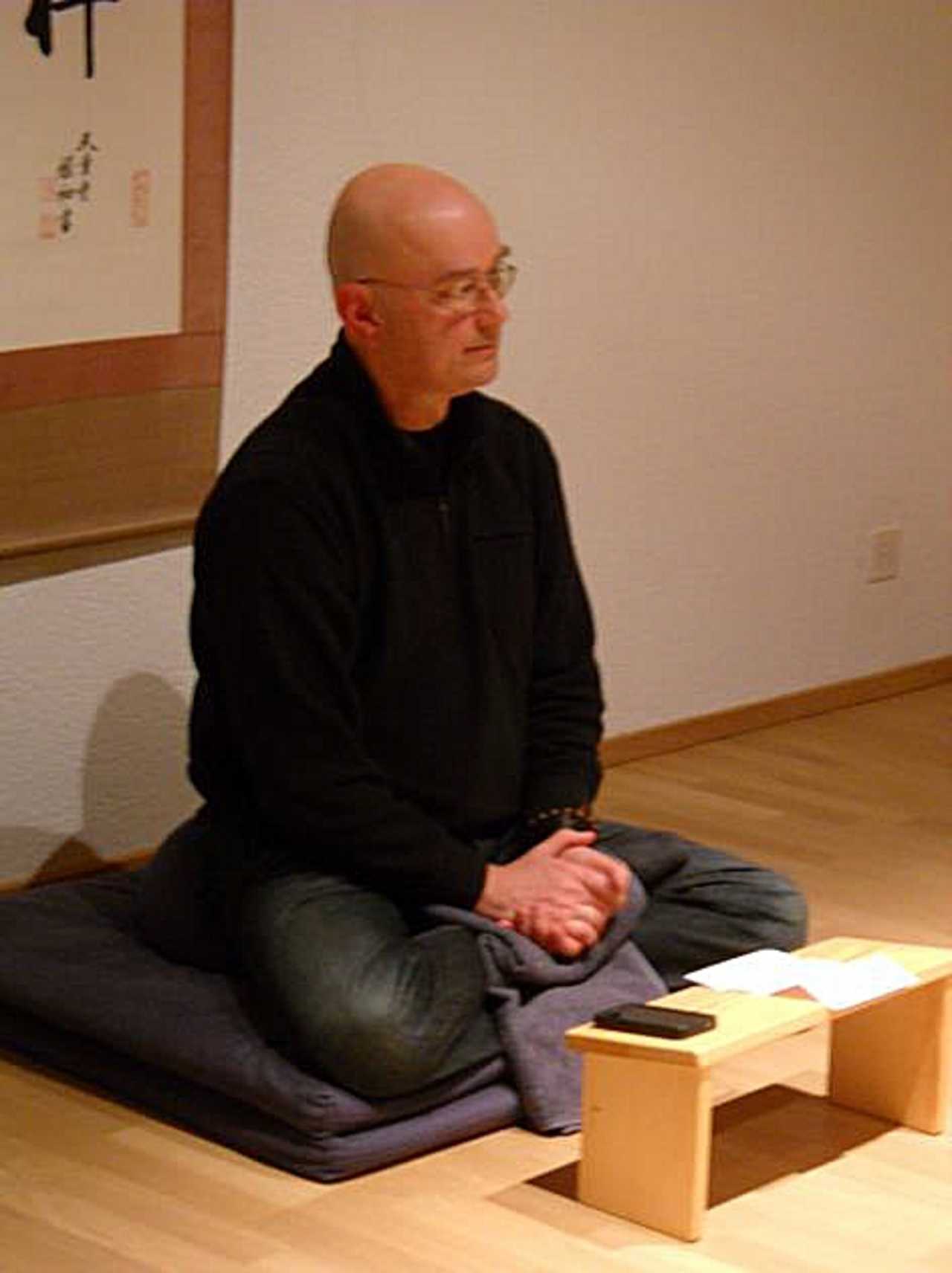

Žarko Andricevic is the Teacher of Dharmaloka – the Chan Buddhist Community, Croatia.

Our incapability to live in harmony with others, the environment and ourselves is a consequence of deep ignorance of our nature and the nature of existence in general. All human suffering, misery and discontent, be it personal or collective, arises out of a fundamental ignorance that is called avidya in Buddhism. Avidya is not common ignorance or what we commonly think of as ignorance. Every person, learned and unlearned alike, may be a victim of such ignorance.

Human maladjustment with the nature of existence has varied throughout the history of mankind and has had consequences that were usually short-lived and local. The harm that one person could have afflicted by actions to oneself or to community or the environment was quite limited. However, since the beginning of the industrial revolution, the incredible development of science and technology has made the consequences of human actions long lasting and global. Today, the World is smaller than ever, while the impact of mankind on the planet has increased to a rate unprecedented in history. Now we are witnessing the global ecological crisis that threatens our survival, the survival of other forms of life on Earth, and nature as we know it.

The global ecological crisis is what comes back to us as our own collective karma. To face the crisis means to face the self. We have to become fully aware that the situation demands much more than superficial changes only. We have reached the point where the sustainability is possible only if we are ready to undergo a radical and genuine transformation of our worldview and behaviour. To be profound and efficient, that transformation has to be reflected in all aspect of our lives – be it personal, social, economical, political or religious. It is good to remember that this crisis contains both danger and opportunity. It is true that we have brought ourselves to the edge of abyss, but this position gives us an opportunity to use the awakened awareness, to start afresh with a life based on the ethics of the common good and cooperativeness instead of pursuing selfish interests and competitiveness.

The process of industrialization, the use of fossil fuels, an ever-expanding consumption of goods, humanpopulation overgrowth, pollution of soil and groundwater, the increase in greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, melting of ice, a rise in sea levels, the shortage of drinking water and food, the extinction of animal and plant species that ultimately threatens the survival of human race – all this constitutes the cause and its consequences that has been undeniably established and largely understood by uncorrupt and wise members of the scientific community. The alarming phenomena of today are only among many symptoms of uncaring human actions such as economic exploitation, wars, religious and ethnic hatred, to mention only a few.

To struggle against these phenomena on the individual and local level, as they appear, means to deal with the symptoms, and not with the causes. However positive and necessary such actions may be, unfortunately they have never yet been universal, efficient or permanent.

The crucial question is where the true causes of the crises lie, what is their nature and how to eliminate them? If we stop for a moment and look closely and deeply into the current crisis, we will inevitably see ourselves. The deeper we look, the deeper we will get onto our own self. What is it in us, human beings, that is responsible for the situation that we got ourselves into? What are the traits in us that lead to the causes of the crisis? Are these the worldviews and attitudes that we hold or are these emotions that govern our behaviour? What is it in us that makes us so destructive to ourselves and to our surroundings? This is actually a question about who we are in the first place. If we were utterly honest and open in our inquiry, without inclination to any theory, we would arrive at a conclusion that we do not know the answer to that question. And, if we reach that point, we will realize that most of our problems stem exactly from our conviction that we know everything about every thing in the world. We all have our identities, ethnicities, religions, names, personalities, our special life stories, our virtues and faults, our professions, talents, hobbies. We have a multitude of roles. We put huge efforts into maintaining the belief that our own identity is solid and to sustain the self-image that we want to present to ourselves and to others. But who are we, really?

The very awareness of that question may help us to find the way out of the clouds of mental constructions and ground us in the here and now, in the reality of the present moment. We may then discover that in our self-preoccupation we find very little place for others, for nature, for the reality in which we live. A peculiar paradox of egocentrism is that the more we want for ourselves, the poorer and the more unsafe we feel. The feeling of alienation, separateness and confrontation with the world is what we call illusion of separate existence. Because of it, we view ourselves and the world through a prism of our own narrow interests that are constant source of conflicts at all levels. Guided by an illusion of duality of the self and the world, we have used modern technology to create the crisis in which we find ourselves today.

The belief in the illusion of duality makes us unaware of our own nature and of the nature of life in general. We behave as if we were going to live forever, we hold on to things as if they were eternal and as if we can truly own them. The world exists for us as subordinated to the human race and other beings are seen as living to serve us. This anthropocentric and egocentric perspective is narrow, shallow, harsh, painful and dangerous, and misses a wider context and the subtle nature of the phenomena as they are. We are not aware of impermanence and the fragility of life. We are not aware of the opportunity that we have been given by life.

We are not aware that the suitability of our planet for life is not absolute, but rather it depends on a fragile balance of a series of causes and conditions that are fluctuating and inconstant. The mankind living on this planet may be compared to a bull in a china shop, clumsy and uncaring, moreover too overbearing, arrogant and aggressive to look at its own face and ask – who am I, really? We are not aware of all this because our awareness is captive to our own egocentrism. When we are full of ourselves, there is little place left for anything else. Being full of oneself means wanting to own everything else, wanting to become master of everything else. That is the source of our troubles, the condition that makes our nature full of conflict and our experience painful. It is of critical importance to free ourselves from such false views on separate existence, from arrogant views on the superiority of humans over other forms of life and nature itself. Only if liberated from egocentrism can we really become aware of ourselves, of others and nature as intertwined phenomena, deeply interrelated and interdependent. It is like a cup of tea, when it is full there is simply no space for some fresh tea. Likewise, with us, if we want the world to unfold in its entirety and in its full splendour, as it really is, we have to escape the egocentric perspective.

In our deluded condition, we think that the skin is a boundary between the self and the outside world. Everything that happens in our body we see as internal, and all that happens outside we see as external. This is a narrow understanding of one's self in opposition to the world. The expanded self draws within itself things from the outer world that are considered to belong to it or with which it identifies. However, no matter how the boundaries are shifted, the self stays separated from the whole, opposed to and conflicting with the rest that it has not incorporated. If we free our minds of self-concepts and if we start to observe ourselves carefully from one moment to the next, the myth we think we are will begin to dissolve. We may see that the body with which we identify, internal and separate from the outside world, is actually sustained thanks to the environment through air, water, food, warmth, light, gravitation, other beings, people. Without air we would not be able to live more than a few minutes, nor without other elements that we consist of. Our body is made up of the same elements that make our planet, and the universe.

From that perspective, our body is not ours at all. It is an inseparable part of nature that surrounds us, it belongs to nature and to nature we “return it” upon death. If we succeed in liberating our mind from an egocentric perspective and the rigid categories that enslave it, we will discover a completely new dimension of our being that is bound to change our understanding of the self, the body, others and the environment. The realization of oneness with the world leads to profound internal transformation. If all people perceived and treated the environment as if it were their own body, we would not have the crisis that we have today. All sentient beings share not only the experience of having a body, but also the nature of their corporeity.

Usually we are oblivious of that deep connectedness. We are deceived by our superficial, shallow and scattered ordinary mind that sees only differences – in species, shapes, sex, and colour. If we look even deeper, deep inside our being, we will discover that in addition to corporeity we also share in the experience of life. The common denominator of human experience and the experience of all sentient beings is suffering. Birth, illness, old age and death connect us deeply, these are experiences to which we all are subject and that we all share. Dhammapada says: “You too shall pass away. Knowing this, how can you quarrel?” How far have we got from that truth, the insight that what we have in common connects us more deeply and strongly than the differences, of any kind, divide us.

Going still deeper, we will observe that we do not only share the same experience, but we also share its very nature. We share the same nature of mind and its potential of realizing that nature. So when we, observing our mind, recognize how relative all views, perspectives and beliefs that we hold true and absolute actually are, and that these views present merely just another description of reality, only then will we be able to say that we know that not a single thing remains to divide us and make us stand apart. This realization holds the answer to the question – who are we really?

Mankind today is perhaps confronted with the greatest challenge in history. The challenge is so great because we have to open ourselves to a new and substantially different way of living in the world and dealing with that world. If we fail to agree on the fundamental principles of the new way of being that comes from the deep sense of Oneness of people, animals and environment, we will miss the great opportunity that lies in the crisis. The crisis is but a mirror. It seems that the future of life on Earth depends on whether we are ready to look deeply enough to be able to recognize our true face and change the way we live accordingly. We may not get another chance like this, ever again.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2011 Dharma Talks Žarko Andričević Others

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-339