There is No Time. What is Memory?

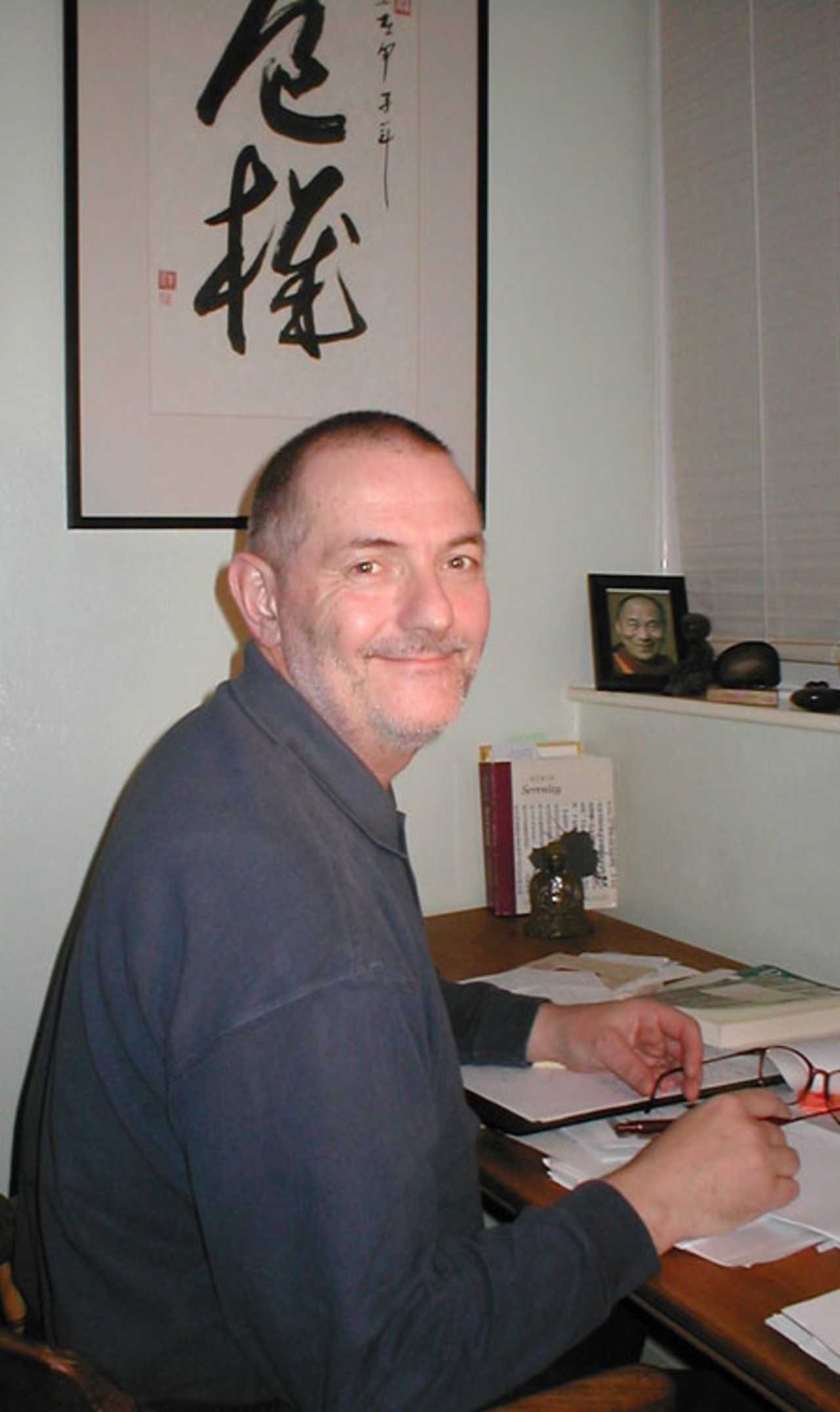

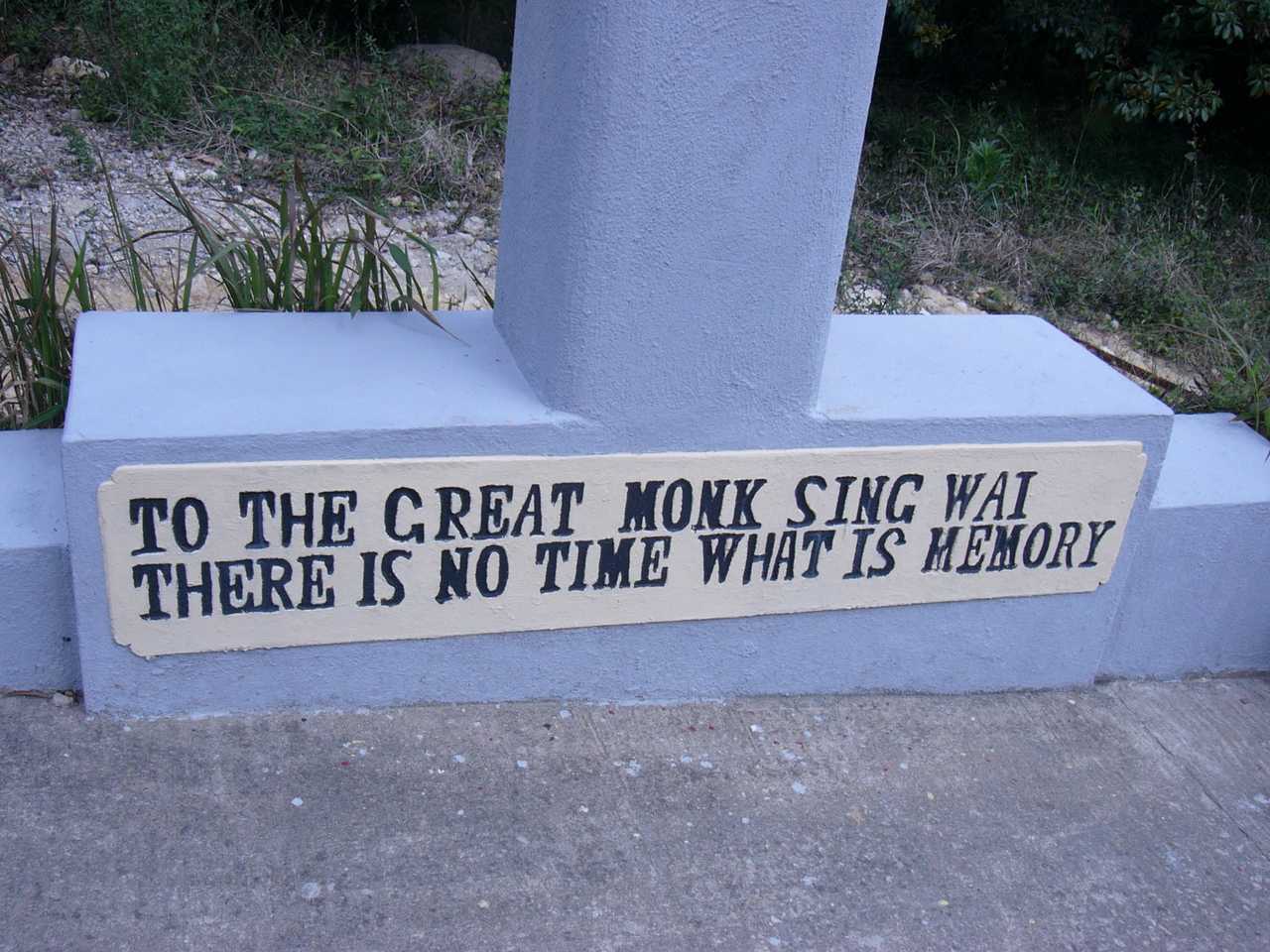

This is a questioning koan that John Crook referred to many times in his talks. His story about his encounter with this was that when he was in Hong Kong doing his national service in 1954, he was taken to Po Lam Chan Monastery on Lantau Island and over an arch leading to the monastery there were inscribed some Chinese characters. Under the arch these were translated as ‘There is no time. What is memory?’ John told the story as part of his narrative about how he was introduced to Chan Buddhism and it clearly had an impact on him in those early years of his practice. I have not been able to find a reference to it in the Chan literature and it certainly is not included in any of the standard collections of koans. However, John used it in his koan retreats when he included it on the list that participants could choose to work with.1

More frequently in talks and informally he would tell the story of when he was confronted with this saying and he would leave it hanging in the air with a sort of “here’s a koan for you to be going on with” attitude. As far as I am aware John never gave any formal teaching or commentary on the koan and it is not discussed in his writings. It is however evident in talking to people who were taught by him that it was a phrase that did indeed stick in the memory. So perhaps now is a time to see if we can unpick it.

Time

Let us begin with ‘time’. From the outset we have a problem in that it is very easy to assume that there is a separation between ourselves and time.

Indeed, one of the things we do is give time a distinct identity and we even put a capital letter on it, ‘Time’, which solidifies it as an object. An object that has some dynamic quality that has an impact on us, a being, as keeping us subject to its whims and movement. But we are not separate from time for, as Dogen has pointed out, being is a function of time and time is a function of being. They are indeed a unity, hence his conception of “being-time” or “the time being”, which is of course the title of one of his best-known fascicles.2

Dogen’s view is that our experience of time has the quality of a sequential passage, but time itself does not move in this way and this is because time and being are not separate, they are unified and identified with each other. Each moment of time as we experience it, being, reflects the past as well as the future. The passage of life is a process constantly changing in an unfixed, non-permanent way and every moment of that process contains a past and a future, a ‘being time’. This becomes the full totality of living life where time and being are interpenetrating at that particular moment. Dogen’s explanation of this in the Genjokoan concerns firewood and ash.

Firewood becomes ash. Ash cannot become firewood again. However, we should not view ash as after and firewood as before. We should know that firewood dwells in the dharma position of firewood and has its own before and after. Although before and after it exists, past and future are cut off. Ash stays in the position of ash with its own before and after.3

As it is difficult for our mind to appreciate and live within the nature of impermanence, it attempts to create a story with a beginning and middle and then we impose a fantasied future on it.4 It is this forcing of a narrative onto each and every moment that is the nature of suffering. Each moment does no hold onto the past nor does it project our expectations of the future. There is no beginning of this moment nor is there any end, everything is continually being present.

According to Dogen, firewood, and ash are things that have existence and have their own time (being time) and each being has its own before and after. Firewood has its own before as a living tree and its own potential future as ash. The ash had a before as part of a fire and a potential as dust in the wind. The firewood and ash can only be experienced in the present moment and it is impossible to actually put a finger on the present moment.

The present moment is the only reality we experience because the past is already gone and the future has not yet come. Yet there is nothing, no actual unit of time, that we can say constitutes the present moment; the present moment does not exist and therefore time itself does not really exist. Still from this present moment which is empty and does not exist, the entire past and the entire future are reflected. This present moment, which has no length, is the only true reality of life as we experience it. And since everything is always changing, at each present moment everything arises and perishes over and over again; each moment everything is new and fresh.5

Returning to our query about ‘There is no Time’, we find that the present moment is the only true reality because the past has gone and the future is yet to arrive and here we find the link to memory because we only encounter the past in the present moment as memories. Therefore, the experience of the past and indeed the future is simply the way the mind is working at this present moment. The actual past does not exist any longer and the actual future as yet to come up.

Memory

When we consider ‘time’ as such, there seems to be something abstract about it but when it comes to memories it very quickly becomes personal because we immediately think of “my” memories. Memories are images, thoughts, feelings, snippets of stories, the recounting of events, etc., that pop into our mind at various times. Our memories are typically a montage of fragments that are isolated from their original context of the past.

Let us take the example of my memories about my daughter’s wedding several years ago. I remember that it was raining and I remember elements of the ceremony but I can’t remember what we had to eat at the reception and I certainly do not remember what I had for breakfast that day or breakfast the next day. Then when I consider this particular memory, I’m not sure how many bits I remember myself or whether it is me ‘remembering’ because I have looked at the photographs of us on that day under umbrellas. Then there is me forgetting some bits but my wife, unlike me, remembering exactly what was on the menu at the reception. When two people are at the same event there are more chances of them remembering and forgetting different aspects than being able to agree what occurred. Certainly, there is some selectivity in remembering and forgetting and memories themselves are impermanent, they can be lost, forgotten, altered, misremembered and then regained. Different memories come to us provoked by different stimuli and situations. My memory of my daughter’s wedding may evoke memories that you, the reader, have of weddings that you have attended. Similarly, someone may tell us about their childhood holidays and we remember the times we spent on holiday as children and again photographs may provoke such thoughts and remembrances. Indeed, anything in this present moment may suddenly remind us of something from our past.

Memories, however, are not straight forward pleasant stories or images as they can also be negative. These can be things that we don’t want to be reminded of; things that have happened to us; things that we are ashamed of or regret; things that we suffered and times we made others suffer. We can all easily make a list of such memories of our own. Bad memories can even be triggered by positive memories as the process of remembering is not necessarily within our conscious control. For example, something might bring up a memory of a good occasion, such as a celebratory party and as the images flash into our mind we remember a certain person was there to whom we were dismissive, putting them down in front of others. So, from remembering a pleasant occasion the problematic path of memory can quickly lead us to the thought “I am a person who can be unkind and dismissive of others”.

Memories therefore are composed of many bits and pieces. They are held together by the ways in which we have held onto the events and stories of our life. But this is not just of our own making as our narratives, our life stories, are often constructed by those around us particularly when we were children. The thought “I am an unkind person” can very easily be linked to and possibly be provoked by the messages in the memories of a parent saying to the child, “you are very unkind and you are particularly unkind to me”. We also hold memories of things that we have been told about our parents’ childhood, about our parents’ parents and about the way in which our family history has evolved.

So memories contain the stories that link us and contribute to the social sense of who we are and where we come from. However, it is not just our families that impact this social content, as memories and their messages are significantly influenced by the culture that we live in. There are, for example cultural expectations about how mothers and fathers are supposed to behave, with ideas of what is a ‘good’ and ‘bad’ mother and a ‘good’ and ‘bad’ father. There are cultural and familial ideas about how a ‘good’ son or a ‘good’ daughter behaves and at a basic gender level are memories involving ‘boys are like this’ and ‘girls are like that’. These memories are typically evoked in an active behavioural way and they certainly also frame the rules of how we are to behave in certain situations. In many aspects of our social and gendered roles we can easily identify memories that carry the active messages about those roles. On the one side this can be seen positively as creating a sense of our place in the world but there is also a negative aspect for, whether it is in the creation of the ‘we’ or the ‘I’, there are always elements which are not helpful and which have a distinct negative, suffering, impact on us.

A key part of this process of our ‘memory’ is that we come to believe that there is a single thing called memory, some container with a capital ‘M’, that is a repository of what has happened to us and been told to us in the past. We can come to believe that it is something that has substance and it exists in a way beyond our own agency. We can view our Memory container as something we can dip into every now and again or more likely that somehow our mind of its own accord just spills out from the container positive and negative bits and pieces. These bits and pieces will have a coherence for us, as we relate to them and the stories that develop in our mind, they create a unity about what has happened to ‘me’ and what has made ‘me’. We can tend to conceive of Memory as a single process that is somehow not quite in our control but is a part of us and a very important element that adds to the process of defining ‘me’.

This brings us to the other problem about considering ‘Memory’ as a thing for we come to believe that it is ‘True’. We come to believe that the things that are held in our container are more or less the things that actually happened at the time they happened. This certainly is not the case as the ‘truth’ of any event can only be perceived at the moment of its occurrence and this does not even consider the validity of our perception or our interpretation of it at that moment.

Memory is therefore a process of construction and reconstruction as we rerun stories and images of ourselves, thereby creating a sense of coherence. Memory is a process of self-communication, a self-writing and rewriting process. It is something that our mind engages with by communicating with itself; it is not something that emerges from elsewhere. Outside information can influence memory but the influence, (re)writing or (re)constructing, comes from within and memory, therefore, provides a potentially changing account of the past. It is not a neutral psychological process but one mediated by the image and concept that we have of ‘me as myself ’. It is from this conceptualisation that we access the information we hold about our past and hence it is not possible to access the ‘past’ in any unmediated form. However, as memory refers to past events and experiences, memory is neither pure experience nor pure event. It is a complex set of processes and at its core it involves the process of the construction of ‘me’ in the present, utilising a conception of me in the past and through this means our memory contributes to our way of being or experiencing who we are.

Each memory is inseparable from the moment that it is evoked, each memory is a part of the present. When we look at memories there is no container to dip into and pull out different deposits to reveal a ‘true’, perhaps acceptable, self at its bottom. Working with memories requires a constant re-looking at what arises in our mind and interrogating ourselves in what is an ongoing process of the changing ‘self ’. In this way memory is always a representation viewed from the present. The only vantage point when considering the past is the present. There is no past insisting on its rightful place in the present. Memory is used to construct the self of the present, but memory itself is not the present; it is our experience of the moment that is the present.

In working with memories about the self, the feminist photographer Jo Spence spent time surveying her family photographs of herself as both a child and an adult and she describes the process of thoroughly questioned (the)? meanings and messages that her memories evoked. Then in a way similar to those with experience of mediation she found that “this reworking is initially painfully, confusing, extreme. As I become more aware of how I have been constructed ideologically, as the method becomes clearer, there is no peeling away of layers, to reveal a “real” self, just a constant reworking process. I realise I am a process.”6

Hence memory is a part of the process of the construction of self and our conception of memory fits in only with the dualistic notion of time as a linear process. Our mind tries to tell us that we have a past that directs us and this results in ‘me’ being who I am at this moment and possibly who I dream to be in the future. But, as we have seen, time is not linear, there is only this moment and we are able to be in this moment and then this moment, and then this moment. In the experience of just this moment there is no past or future and as Ken Jones puts it in his haibun on our koan: “Our storyteller is gone, and the past with him. Our dreamer has disappeared, and the future with her.”7 So if there is just this moment and just this ‘self ’ now, perhaps, we can look at “There is no time. What is memory?” and change it to “There is only this moment. What is self?” (and beware of capital ‘S’). Or, indeed, to place it in a context we might all be familiar with “Now! Tell me who you are?”

Notes

- Sue Blackmore provides a retreat report of working with this koan https://westernchanfellowship.org/dharma/library/article/ten-zen-questions/ This is an extract from the book Blackmore, S., (2009) Ten Zen Questions Oneworld, Oxford.

- Dogen, ‘The Time Being’ in Kazuaki Tanahashi (ed) (2012) Treasury of the True Dharma Eye. Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo. Shambala. Boston.

- Dogen, ‘Genjojoan’ p2 in Shohaku Okumura, (2010) Realizing Genjokoan. The Key to Dogen’s Shobogenzo. Wisdom, Boston, MA.

- Ruth Ozeki, a Zen Priest and writer has written a very interesting novel on these themes in which its narrative poses questions about our experience of time. Ozeki, R., (2013) A Tale for the Time Being. Cannongate. Edinburgh.

- Op cit Shohaku Okumura, (2010) p120

- Spence, J., (1988). Putting Myself in the Picture. A political, personal and photographic autobiography. Camden Press. London. p97

- Ken Jones wrote a haibun inspired by this koan, ‘There is no time. What is memory?’ which can be found at https://www.kenjoneszen.com/publications/out_of_print_publications/arrow_of_stones

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2023 Other Articles Eddy Street

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-561