Chan and Writing the World

I clamber over the stile, and climb toward the Callow Drove, which runs along the ridge above me. The path follows a farm track across a field. Sheep are grazing on grass still frosted where the winter sun doesn’t reach it. A heavy tractor has left deep grooves, hatched with the marks of coarse tyre treads, in the frozen mud. Leaving the field, the path becomes more rugged as it climbs steeply through neglected, copsed woodland, rough rocks slipping underfoot. Breathing the frosty air deeply, about half way up I pause for breath and look around.

There is a movement—brown—to my left. I turn to see a hawk flying in the woods. Bigger than a kestrel, smaller than a buzzard, brown backed, agile: a sparrow hawk effortlessly navigating the narrow gaps between the trees, flying quite slowly. I imagine she is hunting. She makes a tight circle toward me and then is away, back down the hill in a wide arc over the path.

Part of me flies off with her and then returns. I continue my walk up the hill.

This walk is part of a five-day retreat at Winterhead Hill Farm in the Mendips, the house of my friend and Buddhist teacher John Crook. I am exploring how meditation practice in the Chan tradition1 might show me a way toward a practice of participation. What does it feel like to meet the world not as a collection of objects but as a community of spontaneous, mysterious subjects?2 But I am not at all sure what it means to experience myself and the world in this way: as part of, rather than apart from, the more than human world.

The sociologist Max Weber famously wrote that modern culture had resulted in the ‘disenchantment of the world’. So we might see a world of subjects ‘enchanted’, in the sense that Freya Mathews uses the word: the world and its subjectivity awakens, in a literal sense, to our song.3 This is characteristic of fairy stories, in which the hero or heroine steps out of their everyday life into a world encountered as living beings, holding the possibility of transformation and transfiguration. Things are no longer as they appear; this thing here, that thing there.

The Buddha taught that life is characterized by suffering caused by attachment to a transitory world, and in particular attachment to an illusory sense of a permanent self. It seems to me that this illusion of separateness and permanence is one way we stop ourselves participating in enchantment. I set up this retreat to explore how meditation practice over an intensive period might help to loosen my bonds of attachment to ‘Peter’ as a separate entity and, through this, offer access to a participatory and enchanted experience of the world. I want to see if I can ‘write the world’ as a participant, rather than as an observer.

All these words are unsatisfactory, maybe delusional: hence the importance of practice and why I have arranged this retreat.

Once I am settled into Winterhead on my first day, sitting at the table in his kitchen over a cup of tea, John and I talk through how I will spend my time. We agree the simple routine I am following: I sit in meditation for two 30 minute sessions, with a brief stretch in between, four times each day: before breakfast, late morning, late afternoon, and in the evening before bedtime. Between these sessions, I take walks around the garden and further afield in the Mendips, walks in which I attempt to maintain a meditative quality of attention. John agrees to talk with me about my experiences from time to time through the retreat. I make occasional audio and written notes. The rest of my time is spent doing little jobs for John around the house, preparing and clearing up my meals, and sleeping.

The brief encounter with the sparrow hawk takes place on the second day of my retreat. My practice to this point has focussed on becoming fully present — leaving behind all the activities of my everyday life and calming my mind, the starting point of most meditation practices.4 Like most people, I am always busy with thinking and feeling, reflecting and planning about my business in the world. However worthy this may be in its own right — and I am enormously committed to the projects in my life — the Buddha dharma tells us that this busy mind is also devoted to establishing and maintaining our self-image and the illusion of our separateness. So much thought divides us from direct experiencing of the world.

I don’t find it easy to slip into my practice. It is a struggle to establish the alert yet relaxed posture — even using a meditation stool my knees and angles feel bent out of shape. As I focus on my breath, noticing the inhale and the exhale and the pause in between, my mind wanders around, running off into distractions — what is the best recipe for the leek and potato soup I will make for lunch? How cold will it be for the walk outside? What is the best way to mend the chair John has asked me to attend to?

Meditation teachers tell us that distraction and wandering thoughts are ever present; and, as emotional barriers are lowered, the practitioner may also need to confront buried distress and the unfinished business of earlier life. I talk to John about my wandering mind, and he laughs kindly, reminding me again how common this is. The skill, which is gradually learned and re-learned, is to gently bring attention back to the breath and over time discover an experience of quiet being. This process of calming the mind is common to many meditation practices and is traditionally called samatha.

By the afternoon of the second day, I am able to establish quite long periods of quiet mind, and take these qualities on my walk up to the Drove—where I meet the sparrow hawk. Would I have even seen the hawk, so quiet and brown against the fawns and greys of the woodland, if my mind had not been quiet? Would the hawk have even come so close to a busy mind? How would I know and does it matter? It is a gift, spellbinding, to see a wild bird just doing her own thing for her own purposes.

The point of Chan practice is not just to calm the mind but also to radically confront the illusion of a self separate from the world. Once a degree of calm is established, the Chan method is to focus on the whole body and become open to its wider context. This is ‘silent illumination’ through which, with time and practice, one can develop into a relaxed ‘one pointed’ experience, ‘present in the presence of the present’ as John puts it: I am simply here, at ease with myself and with my surroundings, noticing the world around as it arises. From this place of ‘self at ease’ the quality of mind begins to change, and experiences of spaciousness, of timelessness, of bliss may spontaneously arise.

On the third day the weather is bright, and I try meditating outside, looking over the fields toward a small wooded area. It is not easy to sit comfortably, but nevertheless sitting is calming and quiet. It rains a little, not really enough even to wet me, I just hear very gentle pattering on the leaves. And then the sun slips out from behind a cloud, and all of a sudden I am wonderfully warm. That is the right word ‘wonderfully’: it feels like a charm or a gift of brightness. Looking over the field, I can see little drops of water from the rain hanging on blades of grass, glistening in the sunshine. And with the warmth of the sun comes a feeling of movement in the air. It was as if I am directly experiencing the power of the sun to drive the cycles of Gaia—why do I write ‘as if’? I am at that moment directly feeling it in my own warming up.

Then the clouds come over the sun again and everything cools down quite suddenly.

Looking up at the clouds shading us, I realize that as they shade the Earth they reflect the sun, part of the albedo5 effect that keeps the earth cool. I realize how we usually see only part of the total arc of the climate system. We maybe cross with the cloud on this winter’s day because it obscures the sun, but don’t see it is also part of a larger cycle that is keeping Gaia cool so it remains inhabitable for animals like us. It is so easy to grumble about the wind or the rain, rather than seeing it as part of a cycle of weather.

In this meditation, my awareness is drawn to the cycle of the wider Gaian system in which I am embedded. I am for a moment less bothered by getting wet that in wondering about the coming and going of the sunshine. What does it take to see oneself as part of the wider cycle? I suspect that quietening the mind allows some clarity: I become less attached to immediate concerns and purposes, which narrow vision, narrow understanding, narrow what we can experience. I become just a little more able to experience the wider system of which I am a part. But am I experiencing it or thinking about it?

As my retreat continues, I grow to appreciate the contrast between sitting in the Buddha room and walks outside in the January cold. The Buddha room is small and bright, with windows on three sides. John has filled it with the iconography of Chan and Tibetan Buddhism: there is an altar with a small statue of the Buddha, and another of Avalokitishvara, the Bodhisattva of loving kindness; on the walls are silk drawings from Buddhist mythology; in the corner sits an almost life-size Buddha, brightly painted and bedecked with a Tibetan ceremonial scarf; in the opposite corner a large Tibetan drum.

At the start of each session, I light a candle and an incense stick on the altar and bow in respect to the Buddha and the teachings—that’s about as much ceremony as my Nonconformist background will easily accept. But the incense and the images are reminders of why I am here, each time I enter the room they draw me more profoundly into meditative practice.

The following day my experiences deepened. I had been sitting quietly using silent illumination and whole body awareness. In time my mind became quite still: I was just watching the movement of breath and body with a few thoughts trickling through the back of my mind but none staying attached. Following Chan practice, I opened my attention to my wider context. Immediately I did so, without any volition, intention, or expectation, I found myself in unbelievably extended space: one wide sweep of awareness took in the universe as a whole. In place of my everyday experience of perceiving from the centre of my embodied self, I was an indescribably minute being in the vast, vast reaches of a space that was in some senses alive. I was a speck within this whole, experiencing my tiny-ness. Yet I was clearly within and part of it all, part of this whole that was comprehending itself in some way, looking back on itself. It is as if the universe itself, rather than I, was doing the meditating. It left me feeling giddy.

This is an inadequate description. Necessarily so, maybe.

My sceptical self wonders about the authenticity of this account. Is it not odd, I say to myself, that you have created the kind of experience of being part of the whole that you are seeking to articulate? Is this not just fulfilling your expectations? And yet, and yet, I reply cautiously, while I can describe what happened in terms of my ideas, the experience itself took me completely by surprise: I had no idea that at that moment I would be catapulted into a space that was itself meditating. (And of course, this conversation between my sub personalities indicates that I am a long way from letting go of the illusion of myself!).

The following day the experience of spaciousness arose again while walking. I stepped over the stile that leads from John’s garden into the field, and walked through the gap in the straggling hedge down toward the main track. The field dips down into a hollow where there is a trough for cows to drink at. Nothing special, just a field in Somerset. Beyond the track, which is part of the West Mendip Way, the land rises again. I can see across to the path through the woods where I met the sparrow hawk.

As I walked down into the hollow, I was again overtaken by this sense of spaciousness. I felt that I was no longer a point of consciousness making my way through the world, but that I was in some sense extended into the space. It was as if ‘I’ was no longer centred within my skull or my body: I was reaching out to engage myself with a vastness around me as that vastness was reaching to envelope me. The word ‘vastness’ is a good one, it suggests a space that is undefined and unlimited.

I walked on, climbed another style and crossed the track, part of the West Mendip Way. I had to pick my way over the deep ruts full of crazed and opaque ice and through mud churned up by tractor wheels, some places squidgy, other places, where the sun hadn’t struck on it, frozen solid. I followed the footpath up the steep climb toward the ridge.

As I walked on the spaciousness stayed with me, but now I could play with it in my awareness. I could chose to pay close attention to my immediate surroundings—my feet on the rough track, the trees around me—or I could attend to my participation in this wider space. One moment ‘I’ am directing my awareness, the next I am part of a whole.

As I play with this strange experience of being both immediately here and in a vast spaciousness I get some insight into the koan that has caught my attention. A koan, part of Chan and Zen Buddhist practice, is a paradoxical puzzle, a story or a dialogue that cannot be resolved by the rational mind. Traditionally, koans are stories of encounters between students and masters; but they also arise from everyday life. The paradoxical nature of a koan means investigation of their meaning can liberate the mind and shock it into awareness of its constructed nature. This particular koan had been playing around in the back of my mind for a few weeks.

A group of men, committed environmentalists, are gathered around a campfire. One companion asks, 'Why do we go into wilderness?' and another responds, 'Wilderness treats me like a human being.'6

What a strange thought, that wilderness could treat me like a human being! And am I in wilderness, walking up this muddy churned-up track with barbed wire fences and rusty farm implements lying around? Yes, for this experience of vastness places me in wilderness of the wild Universe as well as the more immediate wildness of the sparrow hawk’s wood. And this is exactly what it is to be a human being: to be a centre of awareness and at the same time utterly insignificant, but a speck. I am both my separate self and part of the whole witnessing the whole. Again, I get that slightly giddy sense of being both tiny and part of it all, of being on Gaia, being in Gaia. Almost being Gaia.

I carry on up the hill, reach the Callow Drove, turn along it, and walk for nearly two hours. The drove runs straight along the ridge between two lines of stone walls that separate it from the farmed fields. The walls are mostly tumbled down, windblown hawthorn and oak growing amongst the scattered stone. At the end of the ridge, the path descends sharply through open woodland. I watch the tiny birds flocking in the trees, wondering how they manage to survive in this long cold winter. There are lots of crows milling around, the occasional croak call of ravens flying past, the mewing of buzzards high above. I keep an eye out for the sparrow hawk I saw earlier in the week although I know she won’t perform to order! At the bottom, the path rejoins the West Mendip Way, and I turn right to make a circular walk.

Coming back along the West Mendip Way, once again, while walking, I focus on my breath and on whole body awareness. After three days of meditation, this practice feels quite accessible. And again I suddenly I feel myself in that curious way inhabiting space more thoroughly. I can feel the mud squidging under my feet, the sweat coming through my long johns, the physical weariness from the walk. But I also feel my awareness has unusual reach so that when I hear the buzzard call it isn’t calling from outside me, because the buzzard and I inhabit the same space.

Two walkers are coming down the hill toward me, maps in hand, picking their way along the rutted track, their boots and gaiters splashed with mud. I feel embarrassed to be standing here as if in another world, at the same time dictating notes into my audio recorder. I am about to flip back into being a socialized person again when a blackbird flies past in the same curious open space as me…

The walkers come closer, and we exchange formal greetings.

'Lovely day for a walk, so long as it stays dry.'

'It gets very muddy further down the track, though.'

Later that evening I discuss these experiences with John. He confirms that they reflect what he calls ‘self at ease’ and points out again that this is a quality of mind available given time, persistence, support and skilled direction. But, as he points out to me again, however much the self may be ‘at ease’ and however beneficial the experience may be, the self is still present. Beyond ‘self at ease’ is a more profound experience where the sense of the self drops away completely and the world is experienced directly. Buddhists call this, ‘seeing the nature.’

Buddha nature then is the ‘world’ seen by the subject in one flowing relationship in the state called ‘true nature’. The sensory mind participates directly in the world process but without dualistic identification as something apart.7

We talk about how this enlightenment experience of dropping the self cannot be deliberately developed or consciously willed. It requires a quiet mind, yet it comes ‘from its own side’ as John puts it, so that ‘without any self-involvement, wishing or desire… the continuing presence of “me” is disrupted.’ This may be triggered maybe by some startling event, or maybe called by the communicative presence of the world. One can create the conditions, the ‘self at ease’, in which this insight may arise, but the insight itself is spontaneous. I think it is evident from my narratives above that I have experience of ‘self at ease’ and I have touched experiences of vastness and bliss. But I have no experiences of dropping the self and of seeing the nature.

However, these meditation experiences have important lessons for ‘writing the world.’ First of all, they point to a difference between knowing through probing and manipulation; and knowing through openness and encounter. As Freya Mathews points out, Western science conceives a world of things without subjectivity, as pure objects. There can thus be no moral or spiritual objection to us laying bare the inner workings of such objects through scientific research; indeed such laying bare is seen as a self-evident good. But if we accept the panpsychic premise that matter is in some sense infused with subjectivity, that the world is not a collection of objects but a community of subjects, the nature of inquiry must change. Intrusive investigation is a violation of subjectivity, for ‘A subject is entitled to preserve the secrets of its own nature’.8

Knowing through encounter must rest on a readiness to let go of fixed views of self and other. Just as one does not truly meet another person if one is primarily concerned with preserving one’s self image and inner dialogue, or with the categories into which you wish to slot them, so it is with the more than human world. I need to be willing to cultivate a quiet mind and openness, to greet the world as sentient other. And then I need to wait for whatever will arise. I cannot make the meeting happen. It comes ‘from its own side’, to borrow John’s term.

We will know we have been open to the extent that we are taken by surprise. I suggest that the authenticity of encounter can be judged from its unexpected qualities. Just as when I genuinely meet my closest friend I do not know how the encounter will unfold, so with the more that human world.

All this seems to be to point to some principles for a practice of participation and for ‘writing the world’, which I should follow on my journey.

I draw on meditation disciplines to quieten my mind

I lay myself open to the world

Each day I write what I have experienced

I ask, what is the world and its beings saying to me?

How is it saying these things?

What is my response?

- Chan is the Chinese ancestor of Zen Buddhism. It emphasizes an experiential understanding of the world through meditation practice rather than teachings or scriptures.

- Berry, T. (1999). The Great Work: Our way into the future. New York: Bell Tower.

- Mathews, F. (2003). For Love of Matter: A contemporary panpsychism. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- This account draws strongly on Crook, J. H. (2010). Meaning, Purpose and Insight in Western Chan: Practice after Shifu. New Chan Forum, 42, 1-18.

- Albedo refers to the reflective quality of the planet that reflects solar energy. Clouds and ice have high albedo, oceans and evergreen forests low albedo. See Harding, S. P. (2009). Animate Earth. Foxhole, Dartington: Green Books, p. 77

- Cheney, J. (2005). Truth, Knowledge, and the Wild World. Ethics and the Environment, 10(2), 101-135.

- Crook, J. H. (2010). Meaning, Purpose and Insight in Western Chan: Practice after Shifu. New Chan Forum, 42 (summer 2010), 1-18. P.12

- Mathews, F. (2003). For Love of Matter: A contemporary panpsychism. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. P. 76

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

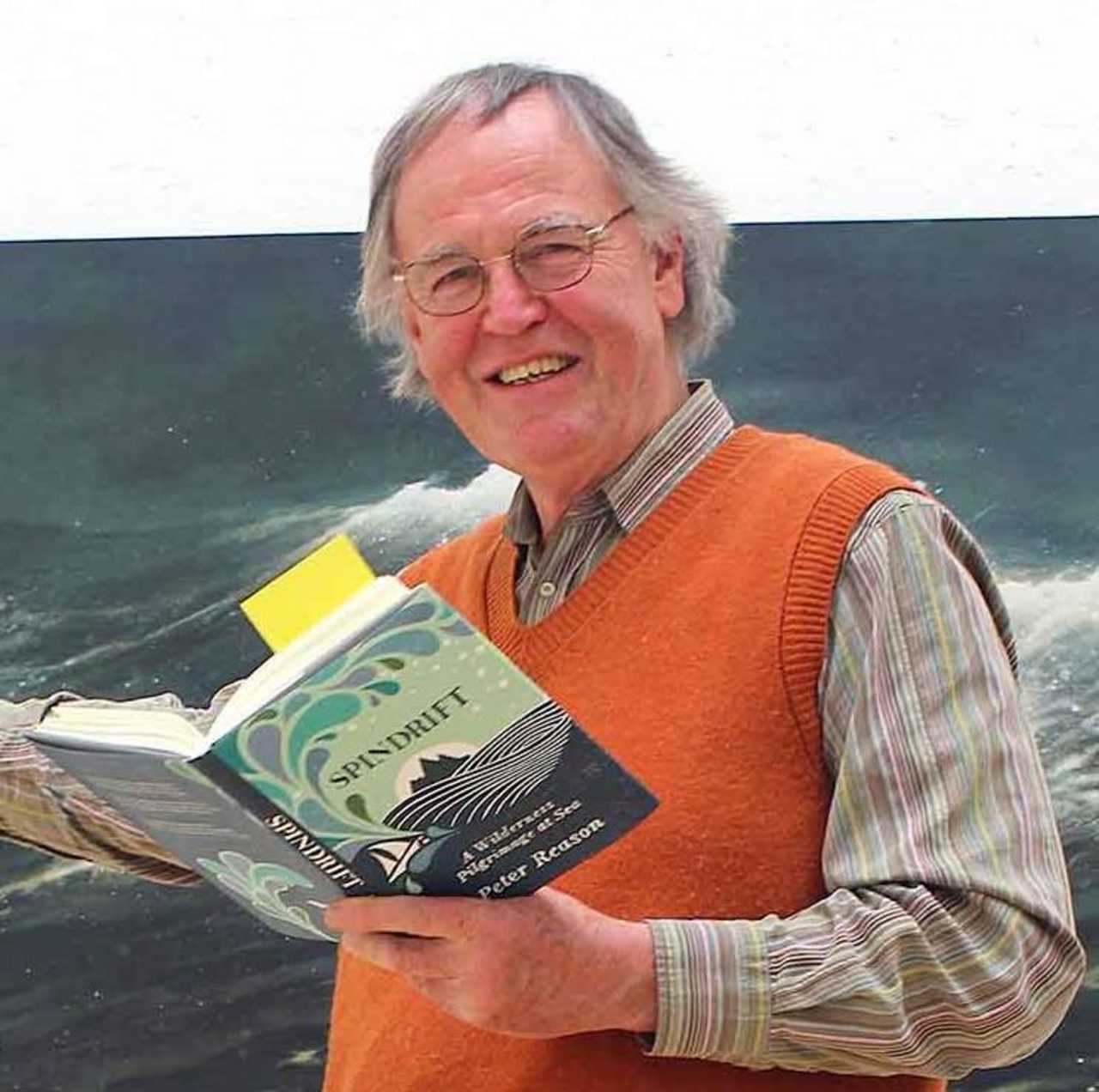

- Categories: 2011 Other Articles Peter Reason

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-322