‘It is Far Better to Light a Candle than Curse the Darkness’

Our retreat teacher in her introductory remarks emphasized the importance of silence: both cultivating our own inner silence and maintaining silence in our interactions with others. Silence meant no conversations, but it didn’t mean that we couldn’t ask someone to pass the butter at lunch time. It did mean, however, that we should draw ourselves away from social contact with our fellow retreatants: walk quietly, avoid eye contact and those tiny non-verbal gestures that can convey so much. But she didn’t say anything about communication by flashlight.

The retreat centre was off-grid, with only gas and oil lamps indoors, as well as a few motion-sensitive lights. Outside, halfway up the hillside in mid-Wales, it was seriously dark, although the moon, waxing toward full during the week, provided lots of illumination. But torches were essential, and everyone seemed to have come with a powerful modern LED light of one kind or another, many worn as headtorches.

As soon as it was dark, the torches came out. There seemed to be an immediate, and maybe unthinking reaction: “It is dark outside, so I need my torch”; rather than, “It’s dark outside, let me take my torch in case I need it”. The same pattern was repeated indoors: as we got ready for sleep and rose in the morning, everyone had their torches lit and flashing across the room. At times it approached the absurd, as when one man kept his head torch alight while brushing his teeth, so the light flashed back and forth with the shaking of his head.

I continually put my obsession to one side in an attempt to return to empty mind, only to have it violently reawakened by a powerful LED light shining straight in my face. And I allowed myself particular pleasure when, in the rest time after supper, I walked away from the buildings into the unlit fields, my wonderfully dark moon shadow going before me.

One of the great disadvantages of lights of all kinds is that they create a pool of light and also their own shadow, a deeper extension of darkness. One’s eyes respond to the brightness and so are unable to catch the glimmers beyond. The more you rely on light, the more habituated you get. In contrast, allowing eyes to grow accustomed to low light greatly extends the range of sight. It is said that human eyes can adapt so as to distinguish a single photon.

We in the modern west do seem to be obsessed with light and enlightenment. The first verses of St John’s gospel, read every Christmas at carol services, tell of the light of Christ ‘shining in the darkness’, and of course that the darkness ‘comprehended it not’ according to the King James Bible, meaning that the darkness was not able to extinguish the light. In Paul’s letter to the Romans we are urged to ‘cast off the works of darkness’, and ‘put on the armour of light’. We refer to the period in the later seventeenth century when the essence of modernity was laid down by Descartes, Newton and the rest of them as the Age of Enlightenment. As Alexander Pope had it, ‘Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:/God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.’

Light is often associated with archetypal masculinity and qualities associated in Taoist philosophy with yang. Richard Tarnas, in his epic account of western philosophy, The Passion of the Western Mind,1 writes that the western philosophical project has been an essentially masculine endeavour. ‘Man’ in western tradition is ‘a Promethean biological and metaphysical rebel who has constantly sought freedom and progress for himself, and who has thus constantly striven to differentiate himself from the matrix out of which he emerged’ by shining the light of awareness and consciousness onto the world. The dark is often associated with archetypal feminine, with yin, the mysterious, the descent, as for example in the ancient myths of Inanna’s descent into the underworld.

Western thought is based on dualist thinking, and radically separates light from dark, subject from object, male from female, human from nature, and so on, denying the dependency of one on the other. Always, opposites are radically separated, one side esteemed, the other invalidated. Buddhist thought, in contrast, holds opposites as interdependent and mutually informing; as John Crook tells us in World Crisis and Buddhist Humanism, experience is an ‘unbroken flow... inner and outer are related’; there is ‘an endless flow of co-dependent arising… a vast differentiating diversity’.2 And of course, ‘form is emptiness and emptiness is form’.

Unthinking, we tend to seek the light and shun the dark. We light our modern LED torches and walk around in their pool of light, blithely unaware of their impact on other people. Not only other people: our modern habit of brightly lighting our towns and major highways disturbs other creatures. It draws insects into the pools of light, and bats in turn to prey on them. This disrupts many biological patterns based on diurnal rhythms and is thought to contribute to the worrying diminution of insect populations. The rhythms of day and night, light and dark, heat and cold, high tide and low tide – and the liminal spaces between them – are important places for biological diversity.3

There is a popular phrase “It is better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness” which in many ways sums up this perspective. It is attributed to many sources, but, like all popular sayings, it draws together many of our Western prejudices in one catchy phrase: light is set against darkness; one small, specific action against the foreboding horror of the dark. It is a phrase unthinkingly saturated with dualist thinking.

It is of course silly to curse the darkness. But it is just as silly to over-value the light. We may well choose at times to light a candle, turn on the electric lights, build a power station. But we might also learn, at the right times and in the right places, to live with and appreciate the darkness. This may mean walking more slowly and with awareness, allowing our peripheral vision and other senses to develop.

It is good to learn to love the dark.

Notes

- Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind. New York: Ballantine, 1991, p.441

- Crook, John H. World Crisis and Buddhist Humanism. End Games: Collapse or Renewal of Civilization. New Delhi: New Age Books, 2009, p.144

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/nov/22/light-pollution-insect-apocalypse

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

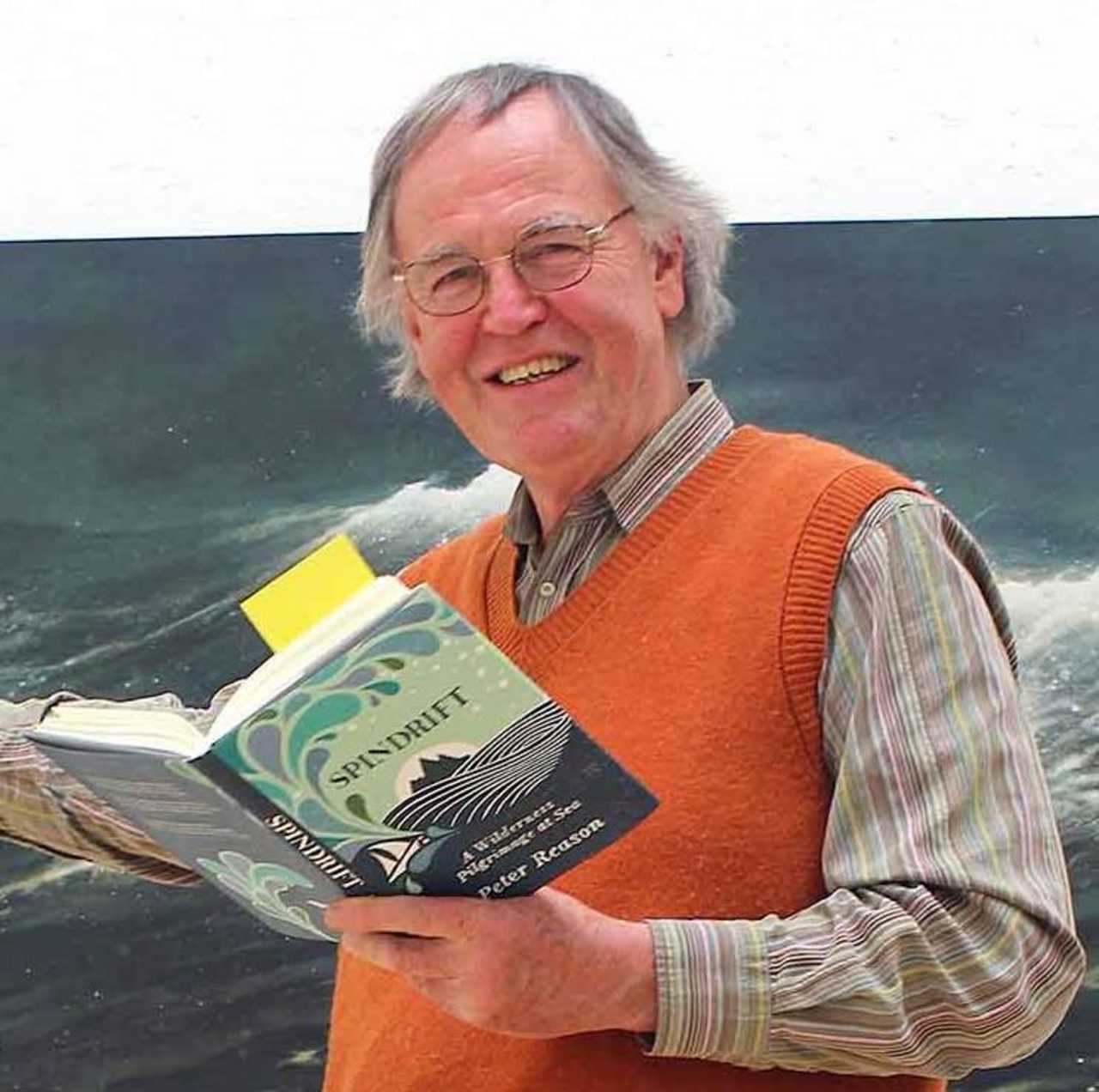

- Categories: 2021 Other Articles Peter Reason

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-586