Life in a Chan Monastery

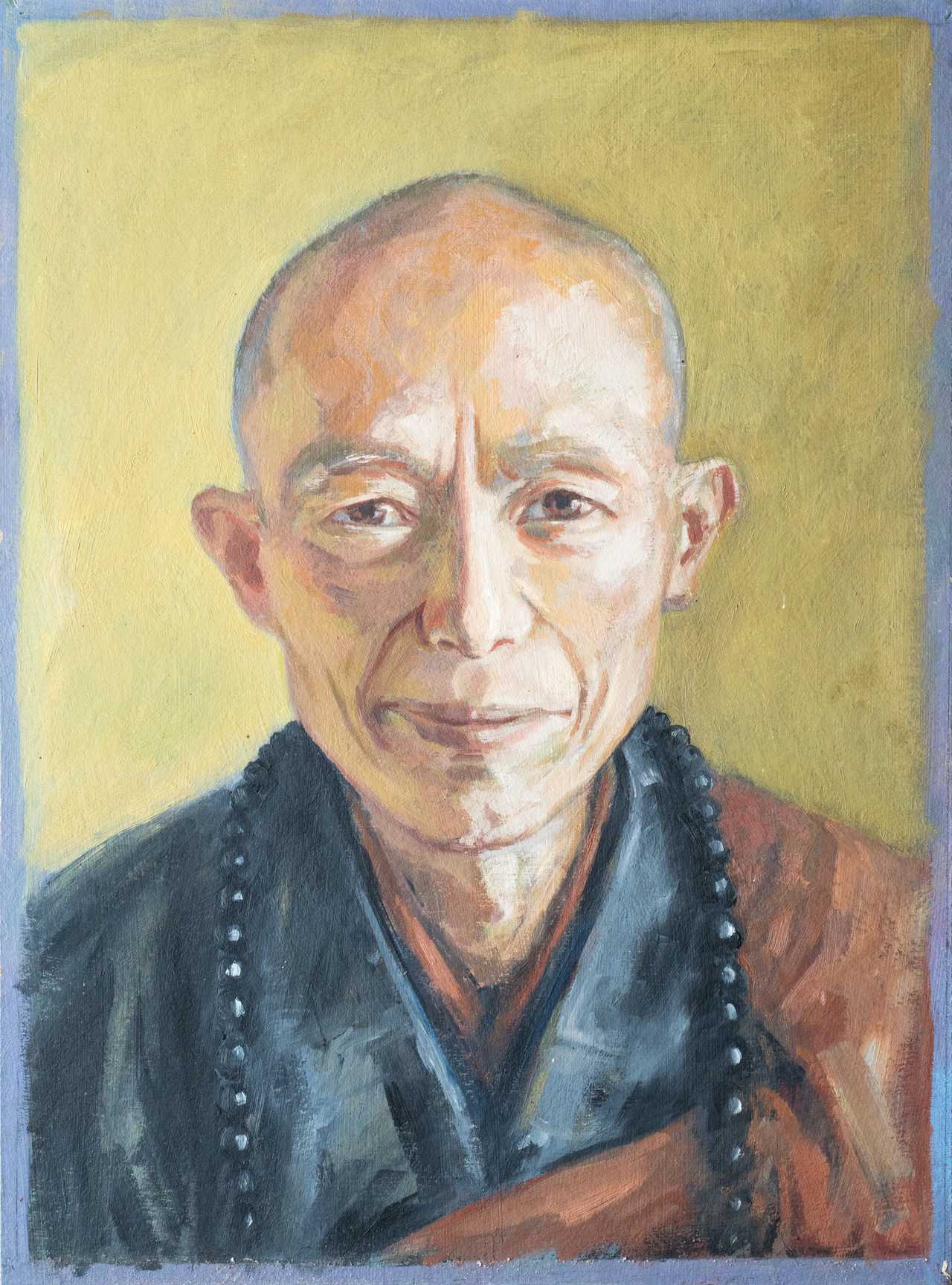

Lecture by Master Sheng-yen at the University of Toronto on October 18th 1991. Edited text by permission from Chan Newsletter No.92, May 92

In ancient Chinese monasteries a practitioner's time was divided between meditation, attending Dharma talks and daily work. Morning and evening was spent in meditation, daytime was for working. We are somewhat ignorant of the daily schedule in early Chan monasteries before Master Pai-chang (720-814). But from the Sung Dynasty (960-1279) onward, we know that there was chanting and reading of the sutras as well as meditation in the morning. Likewise in the evening there would be some chanting or reading before meditation.

In the Platform Sutra the Sixth Patriarch does not put a lot of emphasis on sitting, rather he emphasises practice in daily life. His disciple, Huai-jan (677-744), continued this tradition. But the Fourth and the Fifth Patriarchs, as well as Master Pai-chang in his Pure Rules, specifically mention sitting as an important method of practice. Thus sitting meditation became one of the major methods of practice in the Chan tradition.

Again, in the Pure Rules of Master Pai-chang there is no mention of a Buddha hall for performing prostrations, but a Dharma hall for listening to lectures is detailed. At that time chanting sutras and performing prostrations were considered less important than listening to the Dharma.

From records and stories we know that Huang-po (d.850), a disciple of Pai-chang, taught prostration. There is a gongan of an emperor in the T'ang Dynasty (618-906) who, before he became emperor, spent some time as a novice monk at Huang-po's Chan monastery. His curiosity about prostration when he encountered the Master performing this practice is duly recorded.

Once we reach the Sung Dynasty, there seems to have been both Buddha halls and Dharma halls. The Buddha hall was used for chanting sutras and liturgies both in the morning and the evening. Were Dharma talks given regularly? That does not seem to be the case. Within any given month, Dharma talks were scheduled rather infrequently. We don't know which days were specifically designated for them.

There was also an important practice called Universal Invitation. This was a time when everyone was invited to do work at the monasteries. This was sometimes called ch'u-p'o, literally "going to the mountains," but it did not necessarily entail field work. It might include various chores around the monastery. Under certain circumstance, attendance at Dharma talks might be excused. Universal Invitation was mandatory for monks and nuns.

Hua-tou's and gongans became the principal means of practice in the Sung Dynasty. However in the Yuan Dynasty (1264-1368) many practitioners adopted the method of reciting the Buddha's name. Since Chan was transmitted to Japan mainly during the Sung period, this method was not adopted by the Japanese. Often people do not realise the influence of Chinese Chan on the development of Japanese Zen.

Establishing a monastery was never easy. Land and buildings had to be donated by wealthy individuals or officials or the government itself. Typically, the monastery grounds would include a field cultivated by the monks. Some temples had fields quite far off which were donated by people who attended the temple but who lived some distance from it. These fields were often leased as there were not enough monks to work them.

Working the land was simple in the early monasteries. Later on, with the increase of donated land, leasing became common, and some monks took on bureaucratic functions and had to work in the temple office or see to the management of the land.

When I left home, the monastery in which I was a disciple owned much land, so I first learned to work in the fields, those near the monastery and those in the mountains. Since most of us who left home were quite young, we had to learn traditional tasks such as those learned by a young housewife. I had to make, mend and wash my own clothes. I had to learn to plant rice and vegetables, and I had to learn how to cook them. This is the way life is to this day in my own temple in Taiwan, which is called Nung Chan Ssu. "Nung" stands for agriculture. Thus it is a place where farming and Chan are practised together.

When a novice first enters my temple, he or she is first sent to the kitchen to learn to cook. We also ask a professional tailor to come and teach people how to sew. But most of my disciples know only how to mend; few can really make clothes. They don't really have the patience. However, everyone must learn how to shave his own head. Now we have razors. In the past we only had knives and we left lots of scars on our heads.

When I first left home, I was given no formal introduction to meditation or the practice of Chan. When I asked my Master if he would teach me how to practice, he would say, "Aren't you already practising? Isn't eating practice? Isn't sleeping practice, walking practice, working practice?" Once you leave home, you come to see that everything you do is practice.

Most people who begin practice have the idea that there is a specific mode of cultivation, a specific form, a specific method. Most people usually see a physical and a mental aspect to the practice, a need to train the body as well as the mind. But when I was a young monk, there was no such idea. People saw living as practice. They did not delve into the deep philosophy of teaching.

When I was first at the temple, we simply practised. We worked and prostrated. Every day we chanted and read sutras. We were not told their meaning. It didn't matter. We simply went through the process. We cut down on our attachment to the things around us, cut down on the things in our heads, cut down on our discriminations. This was a good method for us. However for modern lay people such training would be inadequate.

Many of my disciples have questioned these methods. With no emphasis on what they think practice is - meditation, prostrations, chanting - they feel that life in the monastery is not particularly different from their lives at home. What's the point? they say. At home we work, here we work. At home we cook, and we cook here too. Why did we bother to leave home? Where is the practice? What would you say to such disciples? Is life at home and life in the monastery the same?

We practise not for personal gain, but simply as a way of life. Once a practitioner has trained himself to the point where the mind is very stable and few discriminations arise, it is very important that he rely on the principles and concepts of Buddhadharma as his guide. Otherwise, practitioners might develop a nihilistic attitude and conclude that there is nothing in life worth doing. This is a mistake and very much misses the point of what practice is about. Relying on the principles and concepts of Buddhadharma, a practitioner will live his life in such a way that he is selfless, yet very much involved in the goings-on of the world. Such a person has a genuine concern for all living beings, and works in a diligent manner for the benefit of others.

You may recall the story in the Platform Sutra when the Sixth Patriarch, Hui-neng (638-713), met with the Fifth Patriarch, Hung-jen (602-675). Hui-neng was sent to the kitchen to grind rice, and it was not until at least six months later that Hung-jen finally explained the Diamond Sutra to him.

Guided by the same principles, I continue to send novice monks to work in the fields or in the kitchen when they first leave home. At first there is really no opportunity to listen to Dharma talks. Many complain. Usually I tell them that if they want to learn, they must do what the Sixth Patriarch did - work in the fields and in the kitchen. To simply begin by listening to Dharma talks will make enlightenment that much more difficult to attain. Life in a Chan monastery brings the body and mind to a gentle and harmonious state. In this way you become receptive to the teachings of the Buddhadharma. Then you can genuinely practice Chan Dharma.

It has been a slow process establishing a good foundation for Buddhadharma in Taiwan. Buddhism there did not have the kind of historical base that it had on the mainland. It is only in the last forty years that we have had real progress. We still have much to do. However, we are working very hard to build a new monastic environment in Taiwan. We have close to 100 acres where we will build a complex inspired by the discipline and the way of life of the great monasteries of the T'ang Dynasty.

Of course I have benefitted greatly from the time I have spent in Chan monasteries, but this was not my exclusive practice. It is because I have continued to work diligently on my own that I have reached my present understanding. In fact, two recent Chan masters, Hsu-yun (1840-1953) and Lai-kuo (1881-1953), both attained enlightenment outside of the monastery, even though they had practised in the confines of Chan temples for many years.

Chan practice is a pursuit of personal wisdom. But how can you judge what wisdom is? Within, it manifests as freedom from vexation. Without, it manifests in the way we interact with what is around us. True wisdom is without discrimination and is always at one with the environment. It is in this external manifestation that you see that the practice is not simply the pursuit of personal spiritual gratification. If you are only interested in your own freedom from vexation and your own benefit, then you are not practising Chan. If you practice only for yourself, you may achieve some level of samadhi, a very concentrated mental state, but genuine Chan is always turned outward as well as inward.

Chan begins at the logical point of changing yourself. Once your mental state has calmed and changed, there is a natural tendency to help others. This will effect change in the world around us.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: Highlighted 1991 Other Articles Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-108