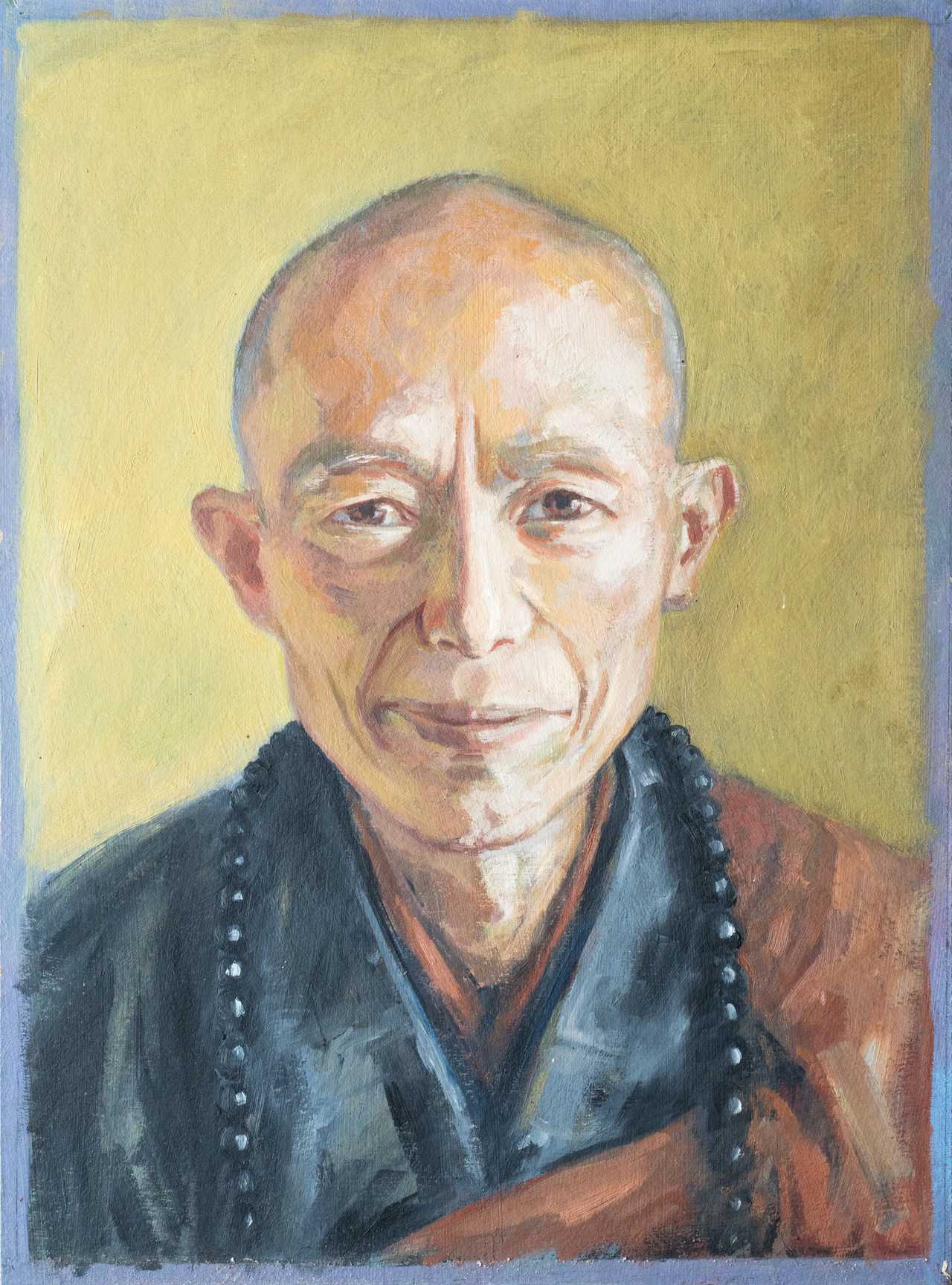

Meeting Shi-Fu

On retreat with Shifu many people have had encounters with him that must have surprised them. Shifu, too, encounters people who surprise him! The outcome of such meetings is often valuable. Sometimes when you meet a Buddha on the road it might be worthwhile seeing what he has to say before you kill him! At the beginning of a new Millennium let us see what happens when you bump into a Master. Of course all stories relate to the immediate context - and yet there is always more to say too. What is that? Here, from Shifu's own accounts, are a few such encounters for you to contemplate. (Ed)

Disturbances can happen even in the seeming quiet of the Chan hall. One woman who attends many retreats always wears a large shawl which she wraps around herself and which she takes with her wherever she goes. At the beginning of one retreat the woman sitting next to her became distressed by this behaviour. In interview she said she was afraid she would experience her retreat as a waste of time because this woman sitting in her shawl next to her seemed so disturbing to her. I said that it was part of practice to remain undisturbed by whatever went on around her and that she should use the retreat as a means to cultivate patience. At the end of the retreat this woman thanked the shawl wearer for wearing her irritating shawl because it had provided her with such a great opportunity for practice. (Chan Magazine 17.3. p5)

A couple came to the last retreat. I told them I was going to seat them far apart so they would not be able to see one another. I informed them that they should not think about each other at all. Both of them replied "No problem. We have been married for many years and the last thing we want to do is to think about each other on retreat!"

It sounded promising but soon, during interview, the woman asked, "So how's my husband doing?" I answered. "Funny - your husband was asking the same question about you only a few minutes ago!" I am sure that many of you have already experienced spending entire periods pondering nonsense. (Chan Magazine 17.3. p8)

On one retreat there were two women who used to massage each other during the work periods. While they respected the silence rule, they never the less signed to each other and slipped off to their room. On the third day one of them came to me.

"Shifu I can't take it any more! What have I got myself into? I'll never be able to sit well on this retreat?"

I said, "You do not have to do these things for her."

She answered, "Yes, I know, but when she comes to me begging for a massage I do not know how to get out of it." What would you do? Could you ignore a fellow practitioner in pain? For most of you such a situation could be very vexatious.

I said "This is a Chan retreat. It is not daily life. You must use the time wisely. You have come here to practice for seven days. That is your prime responsibility - your only concern."

Now these women were disobeying the rules. They should have been with everyone else during the work periods. You must all remember you are here to do a Chan retreat. If you are like the woman with a nagging back pain or any other such problem then you must come to me or one of the attendants. Such matters are our responsibility. We will then try to help you solve your difficulty. (Chan Magazine 17.3. p6)

Practitioners may retire far off into the mountains where they think they can practice without making any discriminations. However such practitioners are still discriminating. They may feel apart from both good and bad and that they are liberated. But if they were truly liberated then it would not matter whether they were in the mountains or in the middle of a metropolis. They are discriminating between the characteristics they read into locations of practice.

Of course there are those who, on hearing this, might ask, "If this is true, why adopt the lifestyle of a practitioner at all? Why consider left-home practice at all? Why not live just as ordinary people do?" The answer is that there is more to being a left-home practitioner than just going on retreats.

Someone once asked me. "Shifu do you discriminate?"

I asked "What do you think?"

He said, "Yes, I think you do discriminate."

I replied "Yes. You are right but why do you think so?"

He answered, "If you were truly liberated then you would go to movies, eat meat, drink alcohol and wear ordinary clothes. You are attached to the role of being a monk and following precepts."

To this I said, "If I were to discard my robe and behave like you then I would lose my position as a monk. Just because you do whatever you wish does not mean you are freer than I. Does having fewer restrictions mean you make fewer distinctions? Why insist that I should be like you? If you are either attached to or bothered by the idea that I am a monk, that I do not eat meat, that I do not drink alcohol, and so on then, in fact, you make more distinctions than I do."

Those who are genuinely enlightened see no differences between monks and lay people. For example, drinking alcohol is considered an act of ignorance, but it is also regarded as a means of wisdom. In the Japanese Zen tradition it is in fact called "soup of wisdom!" Does this mean that ordinary people who drink will acquire wisdom? No, of course not. But for those who already have wisdom and do not discriminate, alcohol and wisdom are not separate, and in fact alcohol can be used as an expedient means to help others.

Chan practitioners who are enlightened may exhibit behaviour different from ordinary monks and nuns. They might even go to brothels, drink alcohol and eat meat. There have been such cases in Chinese, Tibetan and Japanese history. Genuinely enlightened people may look very rough and untidy and their actions are not constrained by formalities. But beware. Are you yet that enlightened? (Chan Magazine 12.2. p3)

Of course, practitioners must still make distinctions. Without the ideas of samsara and nirvana, of vexation and wisdom, there would be no way to make the effort towards realisation. Yet, when one reaches the state of non-discrimination, both samsara and nirvana vanish, becoming part of yesterday's dream. Something that must be left behind or rejected cannot be real. Only that which can be neither lost nor gained is true reality. What this is you must discover for yourself. (Chan Magazine 12.2. p4)

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2000 Other Articles Sheng Yen

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-125