The Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra: an explication

We’ve been reciting the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra as part of the Morning Service. It’s not an easy text to understand so we may end up reciting words blindly without really knowing what we’re reciting. Sometimes, and I don’t think I’ve done it for a while, I talk through the Heart Sutra to give you an idea of what’s in there. We can begin with the title: what it’s about, where it comes from.

Continue to the article text...

Article Contents

- About the author Simon Child

- Prajnaparamita

- Heart Sutra

- The opening of the Heat Sutra

- Emptiness

- A table

- A cloud

- Our self

- All five skandhas are empty

- Transcending all sufferings

- Examining the dharmas

- Nonduality of form and emptiness

- Emptiness of Emptiness

- Emptiness in relation to other teachings

- The Prajnaparamita mantra

- How to practise

- Notes

- Glossary of terms

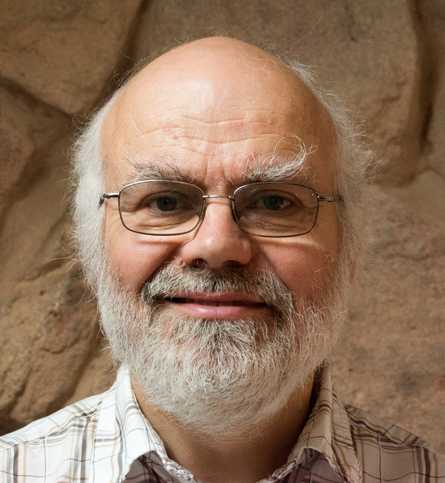

Simon Child

Simon Child 淨宏傳法 Jinghong Chuanfa is the third Dharma Heir in the Dharma Drum lineage of the late Chan Master Shengyen (1930-2009), one of the most influential Chan Buddhist teachers of the 20th century.

Credentials and Experience:

- Lineage: Direct transmission in the Caodong (Soto Zen) and Linji (Rinzai) Chan Buddhism traditions

- Role: Guiding Teacher of the Western Chan Fellowship since 2011

- Training: Over 45 years of intensive Chan practice including multiple 7-day and 10-day silent retreats

- Teaching: Led retreats across Europe and North America since 1998

- Study: Trained directly under Master Shengyen at Dharma Drum Retreat Center, New York USA, as well as with Master John Crook who was Master Shengyen's second Dharma Heir

Professional Standing:

- Authorized to teach Silent Illumination, gongan (koan), huatou and other methods.

- Regular teacher at Shawbottom Farm retreat centre UK, and occasional at Dharma Drum Retreat Center USA and Dluzew Poland.

Contact and Resources:

- Western Chan Fellowship: westernchanfellowship.org

- Email: teacher@westernchanfellowship.org

- Schedule: Western Chan Fellowship Chan / Zen retreats

We’ve been reciting the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra as part of the Morning Service. It’s not an easy text to understand so we may end up reciting words blindly without really knowing what we’re reciting. Sometimes – and I don’t think I’ve done it for a while – I talk through the Heart Sutra to give you an idea of what’s in there. We can begin with the title: what it’s about, where it comes from.

Prajnaparamita

The Heart Sutra is part of a collection of texts going back to around the first century CE. The collection of texts goes under the title Prajnaparamita. You can’t say any one person gathered them together, they were brought together by different people. For example, the traders between India and China on the Silk Route carried their favourite Buddhist texts with them. When they met others they might exchange texts, and in this way they might have a collection of texts that they find useful and interesting. Perhaps when they reached China they sold the texts and used the money to buy silk to take back to India. The texts were to some extent traded and this is partly how Buddhism came to China, because the traders had these interesting texts and the Chinese wanted more of them. Similarly, Buddhists within India might exchange texts with each other. There was a lot of interchange of texts. It was not co-ordinated by anybody, but similar texts, related texts, came together into collections.

The Prajnaparamita isn’t a single text, but rather it is a collection of a lot of individual texts. There are different versions that have come down to us. This version [holding up a thick book] is the Prajnaparamita in 18,000 lines. There’s also an 8,000 line version, also 25,000, 100,000 and 125,000 line versions. There’s a lot of repetition, and it’s a rather random collection of texts which is not very organised. One of the texts included is the Heart Sutra, and another is the Diamond Sutra. Various texts which point in the same direction, though by different means, were brought together.

What does Prajnaparamita mean? We think of paramita, for example, as ‘perfection’: hence, perfection of prajna, perfection of wisdom, insight. These are texts which point towards insight, prajna, in particular insight into ‘Emptiness’ which is a tricky concept that I’m going to say more about. The Prajnaparamita body of literature is pointing towards, and to a large extent asserting, the concept and universality of ‘Emptiness’. It’s not so much a philosophical discussion, it’s more like similes, examples and metaphors to try to help you to understand and accept the idea of Emptiness. Subsequently, in the Madhyamaka, there was a more philosophical development of Emptiness which sought to prove Emptiness philosophically. The earlier Prajnaparamita was more like an assertion, “this is how it is”; “this is what the Buddha taught, what he meant”, using various examples. This is the Prajnaparamita literature.

Heart Sutra

The word ‘Heart’ comes from it being the ‘heart’ of the Prajnaparamita literature. It’s a condensation, it’s the core, it’s the essence – it’s the ‘heart’ in that sense. It’s the heart of the 100,000 lines summed up in one page. A single page is more memorable. People learn it off by heart and recite it from memory. The Diamond Sutra is a fair bit longer but some people also learn that off by heart.

Let’s have a look at what’s in it. What we find is an extremely abbreviated text; a large part of it is pointing to other teachings which are not fully stated or even identified because it’s assumed that you already know them. It’s pointing towards those teachings largely to negate or otherwise reinterpret them, which will have no meaning for you if you don’t recognise those teachings. For people who are reading the texts and trading the texts, they already knew the various teachings to which the Heart Sutra refers. Maybe we don’t know them, or we don’t recognise which teachings they’re pointing at, therefore it’s worth going through that. Let’s have a look through it line by line, picking out things as we go through.

The opening of the Heart Sutra

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara… I mentioned Avalokiteshvara yesterday. Avalokiteshvara is the Sanskrit name for the bodhisattva of compassion known in China as Guanyin, or in Japan as Kanzeon or Kannon, in Tibetan as Chenrezig. I think it’s quite interesting that this key Wisdom text is featuring the bodhisattva of Compassion. I don’t know whether that’s accidental or whether it’s bringing out the equivalence, if you like, of Compassion and Wisdom. You’d think it might be Manjusri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom, telling us about a Wisdom text, but it isn’t – curious.

When the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara was coursing in the deep Prajnaparamita… That’s a nice word, ‘coursing’, isn’t it? How do we receive that word? We can read it as, ‘in a state of deep meditation’. In the other version we were looking at it says:

At that time the Blessed One (i.e. the Buddha) entered the samadhi which examines the dharmas called Profound Illumination and at the same time Avalokiteshvara, looking at the profound practice of transcendent knowledge, saw the five skandhas and their natural emptiness…

Avalokiteshvara was looking at the profound practice of transcendent knowledge/coursing in the deep Prajnaparamita. These are meditative states examining the mind, examining what the mind gets up to: examining the mental phenomena arising and falling, being created and dissipating; in that state of observing the mind, such a state being an entrance to deep insight including insight into emptiness.

…coursing in the deep Prajnaparamita, he perceived that all five skandhas are empty… The word skandha is translated as ‘aggregates’ or ‘heaps’. The idea is that you could analyse the attributes of a human being into five different categories: aggregates; heaps; piles; skandhas – sheep pens, if you like, five sheep pens. There is ‘form’: the body, the physical body, the shape, the appearance, and this is the first skandha. Secondly, ‘sensation’: the fact that we have some contact with the environment. We can appreciate some sense of contact, we’re in touch with the environment, so we have the quality of sensing.

Thirdly, ‘perception’: we have the quality of perceiving, which is a stage beyond sensation – it’s interpreting the sensation and creating a sense of a situation out of it. We touch something, we have a contact, but we interpret it as ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ or ‘spiky’ or whatever it is; we go beyond just the mere fact there’s a touch into “This is a bit too sharp,” or “This is a nice, cool drink”. We’re moving into some mental representation of an object beyond the mere sensation

Then fourthly we have ‘volition’. Volition is the word used in this translation. It’s the word samskara in Sanskrit, translated here as ‘volition’ but sometimes as ‘impulse’, sometimes as ‘habitual tendencies’. I was speaking about how our minds are conditioned by our life experience and we store ways of responding to situations. Having perceived that we’re in one of those situations, the impulse arises to implement our usual habitual response to that type of situation.

There’s a contact with the environment, there’s an interpretation of it – a perception – and that perception matches something in our storehouse consciousness: “I know what to do in this situation – run! It’s a tiger! It might be a tiger, there’s a bit of light and dark, I’m not sure… but, just in case, run!”, and we run. This doesn’t relate only to innate instinctive survival impulses, but also to learned or conditioned responses such as our change of attitude on encountering certain individuals in our workplace. We have these habitual responses represented by the word ‘volition’ sometimes translated as ‘impulse’ or other words.

Finally, the fifth skandha, consciousness. Consciousness is the faculty which appreciates all this, the faculty which registers the sensations. It registers, maybe we could say also produces, the perceptions, and it retrieves the impulse and activates it. Consciousness is a faculty not precisely over all the others but receiving information from the others and processing and organising it and giving us some story of what is going on.

This is a model of the being, which could be divided into these five categories, five heaps, five aggregates, five skandhas. Our friend Avalokiteshvara, in deep meditation, perceived that all five skandhas are ‘empty’: form, sensation, perception, volition and consciousness are empty.

This word, ‘empty’, is very tricky. When we read a word in a text we naturally tend to take the common English meaning of the word, but a lot of the words here are better understood as being technical jargon. They have a meaning behind the word; the English word is an approximation of the meaning, but we need to get to the intended technical meaning behind the word – and this particularly applies to the words ‘empty’ and ‘emptiness’.

Emptiness

Words are labels for some shared experience about the world – we use a word and we will both know what we mean by the word. However the word ‘emptiness’ as used here is pointing to something we don’t necessarily have a shared experience of. It reveals a difficulty in our way of sharing experience by using language, because the language can mislead us. The text is trying to break us out of an habitual way of thinking and perceiving. It’s very tricky because we haven’t got the words to do that. As I understand it, the corresponding Sanskrit word, sunyata, has the same problems as the English word, ‘emptiness’. It’s sometimes also translated as ‘void’, which is no better or perhaps even worse.

When we see this word ‘emptiness’, what we have to do is to mentally replace it with a phrase. The phrase itself needs unpacking, but the phrase is something along the lines of ‘empty of inherent existence’, or ‘empty of independent or intrinsic existence’. For example, a perception: it is ‘empty’ of being that perception all by itself. It has just arisen in response to certain circumstances. It isn’t that it was pre-created and already existing, or that it’s come from somewhere else to arrive now; it’s truly a product of the mind, a creation in the moment. The same for the others: the impulse, the sensations and the form. Yes, even the form, the body – now that might be trickier – we have to think about that one.

The idea is that the being, and also the various parts of the being, don’t inherently or intrinsically exist; it’s more just like a presentation in the moment. That probably sounds a bit weird – it’s very tricky to get. There are different metaphors and similes which are used to try and illustrate this word ‘empty’. I’ll go for one of the common ones: a table.

A table

Imagine there’s a small low table sitting there in the middle of the room: an ordinary table, four legs, a flat surface. We use the word ‘table’ as an object and in our mind there’s a table and there’s no problem about it – we refer to it as a table. What about if a table gets a bit wonky; some mice get in and chew one of the legs so one of the legs is shorter than the others. Maybe a leg is rotten and breaks off. Do we still have a table?

If you put a weight, put your mug of tea, on the opposite corner to the missing leg, it won’t fall over and it will support your mug; you’ll be all right, you might still be able to use it as a table. But put your mug of tea above where the missing leg is, then you’ve got a problem; it’s no longer functioning properly as a table. It’s in a sort of twilight zone between being a table and not being a table – depending on where your cup of tea is at the time. What about if it loses another leg? Then it gets really problematic! At this point we have to confess we no longer have a table.

The question arises: where did the table go? We were quite clear we had a table, there was no doubt about it when there were four legs. Taking half an inch off one of the legs didn’t take the table away. Taking three inches off a leg, maybe even taking the whole leg off, may not completely take the table away. So the table wasn’t in the leg. But when we took away the other leg, we could no longer continue calling it a table. Somehow, taking away two legs ‘takes away’ the table. Is the table in the legs? That way of thinking doesn’t work, but it’s in our assumptions.

If I see a coffee table, and someone comes in and stands on it to reach a high shelf, then suddenly, “Oh I see, it’s a step, it’s not a table; Er, it’s both a step and a table”. It’s confusing. Perhaps someone uses it to prop the door open and now it is neither a step nor a table, it’s a doorstop. I’m labouring it a bit – because you might say you wouldn’t be thinking like that – but our way of thinking assumes that if there’s an object, there’s somehow something there behind or inside the object, making it what it is; that’s our assumption. Asking, “Where did the table go?” reveals that sort of assumption.

It applies to other objects too. Any object that we look at, we look primarily at how it’s useful to us, how we could or do use it, and label it accordingly. We can label that as a table and use it as a table. We could also use it as a step – but especially if that was a regular occurrence then we might refer to it as a step instead of as a table. Same object, just different labels.

There’s something about the function, which is attributed by us, which gives the object its character and identity for us. It’s empty of being a table; it isn’t intrinsically a table, it isn’t intrinsically a step, it isn’t intrinsically either a doorstop or future firewood, but it could be used as any of these things. That usage or that label is not intrinsic to what’s there; in fact, there isn’t intrinsically anything there. You might say there’s some tree, some slices of a tree, but then, what’s a tree? We could go into that one separately.

There isn’t intrinsically a table there, even though we all see a table and use it as a table. Our mind has this way of assuming to be specific objects things which are not inherently what we use them as. Functionally, it’s very useful to do that, very helpful – we know what we can put things on, we know where we can look for things, and if we don’t want to bend down to the floor we’ve got something we can reach for easily and use as a table. We know the attributes of something we look for to be a table, for example to be level, more or less. We allow a bit of wobbliness and a bit of slope, we cope with it to a certain extent – we’ve all got wobbly tables in our houses, haven’t we? But if a slope reaches to 45 degrees then it’s no longer a table.

The table, or step or whatever, is empty of inherently being a table, or a step; the ‘tableness’ is an attribution by us, it isn’t a quality in the object. That’s pointing us towards the idea of emptiness in relation to an object like a table – the object is neither inherently nor intrinsically a table. One of the classic examples in the texts is of a chariot, and if a chariot loses a wheel, is it still a chariot? We can go through a similar sort of analysis with other objects, and the one I often use, because people seem to get the idea, is a cloud.

A cloud

There are plenty of clouds here today to look at. Look at a cloud. We know what we mean by ‘cloud’. We manipulate them as mental objects, referring to them in weather forecasts because they affect the sunshine and rain. We think we have a clear appreciation and understanding of the phenomenon called ‘cloud’, the object called ‘cloud’. Do we?

Scientifically we know that all we have up there are some water droplets, suspended in the air, swirling around a bit depending on the wind and thermals, but not (yet) falling to the ground. Where the droplets are well spread out we call it either a clear blue sky or a bit hazy, and where the droplets are close together we call it a cloud. There isn’t an actual individual object called a cloud, just there are varying densities of water droplets.

If I asked you to go up and find the edge of a cloud, perhaps the bottom edge, how would you know when you’d reached it? The first water drop? That might only be six inches above here. When you reach a certain minimum density of drops? That’s sounding a bit arbitrary, isn’t it. When you get a density of water drops sufficient to block the sight of the blue sky from down here? “Yeah, that’s the edge of the cloud” That’s also a bit arbitrary, isn’t it? What about if you were higher up a bit closer to the cloud – you might see through it a bit better, and you still wouldn’t see any definite edge.

There’s something about the way our mind appreciates a cloud as an object which influences weather, sunlight and rain, and we manipulate that in our minds, in conversation and in weather forecasts: it’s a very useful symbol but there’s no intrinsic object of a cloud, there’s just a certain density of water droplets in the sky. It’s ‘empty’ of being a cloud. ‘Cloud’ is a very useful concept and a term that we use, but there isn’t a cloud there in any meaningful sense as an independent object which is inherently and automatically a cloud.

Our self

People can follow along and ‘get it’ on some level. When it gets really tricky is when we start applying it to objects like this one [points to self] or these scattered round this room [points to audience members]: are you ready to consider yourself as empty? I usually meet more resistance at this point. Are you any different to the cloud? In what way are you different to the cloud? You are a temporary assembly of atoms and molecules in a particular shape, with particular movements inside: circulation-type movements of blood and movements of muscle fibres and things, digestion, movements of mood, feelings.

We have this idea there’s a self: we experience the phenomenon of a sense of self and a sense of presence of it, with an appearance of some degree of control: “I can make my arm move in and out”. We assume there’s something behind that sense, and something guiding those actions. There are a lot of assumptions going on. A very firm assumption of ours is of a self. Unlike a cloud or a table, we would argue there is definitely a self here because that’s what joins all this together, and because we sense it.

Transcending all sufferings

Nevertheless, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara perceived that all five skandhas are empty, thereby transcending all sufferings. That’s quite a big claim, isn’t it? You might not have been so interested in the emptiness stuff but transcending all sufferings – I’ve got your attention now: a bit of click-bait! Master Sheng yen’s commentary on the Heart Sutra is titled, “There is no suffering”. Yeah, 100,000 lines on Prajnaparamita, that’s a bit heavy-going, but transcending all suffering, oh, maybe I’m interested in this; maybe I’ll try that meditation stuff Avalokiteshvara was doing. I didn’t mind about whether he was right about the emptiness bit, but he’s transcended all sufferings – that’s interesting!

Examining the dharmas

Avalokiteshvara is in the samadhi which examines the dharmas. That’s dharmas with a small ‘d’, phenomena, not Dharma with a capital ‘D’ which means the Buddha’s teachings or, in a wider Vedic sense, the law of the Universe. Dharma with a small ‘d’ is ‘mental phenomenon’, any phenomena that we experience. The early Buddhists categorised these minutely. They had a precise list of them (which varies slightly by tradition), the dharmas, the mental phenomena, the arisings, they examine the dharmas.

We’ve been examining the dharmas in our own minds – we’ve been looking into the mind and seeing what we discover there. We discover various things and some of them we’re indeed discovering to be empty. Our impulses to behave in certain ways, we realise that they’re not grounded on anything solid, they’re not grounded on ‘truth’, they’re just arising as echoes from past experience. They pop up and we feel the urge, but they go away again, they dissolve.

Avalokiteshvara was doing this. In the process of doing this he discovered not only that the dharmas are empty but also that these five skandhas are empty, which in a sense is not surprising because they’re mental constructions created from the dharmas. Our knowledge of the five skandhas is from our mental impressions of them.

The opening lines were a statement of the context as to how the Heart Sutra came to be spoken. The longer version we’ve also been reading has a preceding paragraph explaining the scene where the Buddha was assembled with his followers on Vulture Peak Mountain:

Thus have I heard: once the Blessed one was dwelling in the royal domain of Vulture Peak Mountain, together with a great gathering of monks and Bodhisattvas

It says that Buddha entered samadhi examining the dharmas, the samadhi called ‘Profound Illumination’, and at the same time Avalokiteshvara was looking at the profound practice of transcendent knowledge and saw the emptiness of the skandhas.

Through the inspiration of the Buddha, Sariputra asked a question of Avalokiteshvara. Avalokiteshvara was asked, “How should those noble ones learn, who wish to follow the profound practice of transcendent knowledge?”

Avalokiteshvara replied, and the rest of this text is Avalokiteshvara’s response. Avalokiteshvara starts by saying Sariputra, form is not other than emptiness and emptiness not other than form. That’s what I’ve been talking about: form is empty, all the skandhas are empty.

Nonduality of form and emptiness

There’s a problem in this use of language because the noun ‘emptiness’ might be assumed to represent an object. The teaching on emptiness is removing the idea of an object, so again we’re caught by language. Form is empty, form is not other than emptiness, it’s just trying to get over the fact there’s nothing behind our perception of form.

Sariputra, form is not other than emptiness and emptiness not other than form

And in case you haven’t got it, he repeats it with emphasis:

Form is precisely emptiness and emptiness precisely form.

The repetitions say, ‘you’re not getting away with dismissing this, I really mean it’. Also the word ‘is’ in here is important, because so often people hear this as ‘there’s form and there’s emptiness’. That’s not what he’s saying, is it? He’s saying form is emptiness and emptiness is form. Form is precisely emptiness and emptiness is precisely form. He’s not saying there’s emptiness and there’s form; he’s saying form and emptiness are the same thing, at the same time.

This is a point which is commonly missed or is misunderstood – hearing it as suggesting there are alternate realities of emptiness and/or form. But no, form is emptiness, emptiness is form. It’s pointing towards there being different ways of perceiving the same phenomena, different ways of interpreting or understanding the same phenomena – but still there is this phenomenon that we’re experiencing, this moment.

To see it as form overlooks that it’s empty, but also to see it as empty could overlook its form. Therefore he expresses it both ways and emphasises it. But then, to ensure you understand, he explicitly applies it to the other four skandhas too: so also are sensation, perception, volition and consciousness. In other words, sensation is empty and emptiness is sensation. Same for perception, volition and consciousness. All five skandhas are being asserted to be empty. These five skandhas were a common philosophical understanding, analysis of a person, but the Heart Sutra is saying hold on, form is empty, sensation is empty, perception is empty – don’t go away with the idea of five skandhas and believe you’ve got it.

Emptiness of Emptiness

It goes on. We have the word ‘void’ coming in now – ‘void’ is sometimes used as an alternative to ‘emptiness’ but ‘void’ is an even more tricky word. ‘Void’ presents a blankness to the mind – it does for me, anyway – but we find the word ‘void’ being used because of the lack of more suitable words. Sariputra, this voidness of all dharmas – we could hear that as ‘emptiness of all dharmas’ – is not born, not destroyed, not impure, not pure, does not increase or decrease. This is trying to relieve us of any misconceived idea of voidness or emptiness as being another category of thing. We had the wrong idea that there was a cloud thing in the cloud. Should we instead think that there is a thing called ‘emptiness’ in the cloud? No, that’s not it either.

In case you’re falling into that trap, some versions of the Heart Sutra specifically say emptiness is also empty, i.e. asserting the emptiness of emptiness. As a noun ‘emptiness’ could be treated as a thing and in doing so we would fall into the same trap even while we’re hearing the teaching on emptiness. This version of the sutra is one such. In saying: this voidness of all dharmas: it’s saying the emptiness of dharmas is not born, not destroyed, i.e. the emptiness of dharmas is also empty. A beginning understanding of emptiness could lead us to think of emptiness as the one true thing; no, emptiness is also empty: this voidness of all dharmas is not born, it’s not destroyed, it’s not pure, it’s not impure, does not increase or decrease – you can’t apply these categories to it.

All five skandhas are empty

Avalokiteshvara perceived that all five skandhas are empty: form, the body, the shape, the visual impression is empty. He’s pointing to the same mistake as assuming there’s a cloud in the sky as an object. The appearance of form of a person, just as the appearance of cloud, does not mean there is some thing intrinsically there.

Sensation: our sense of sensation is empty. It’s a little bit more tricky to untangle that one, but it’s pointing again to the idea that well yes, there’s something going on there but to have it as an intrinsic definition, an inherent identity, that’s a mistake; it’s merely something transient, arising and passing: sensation wasn’t there, then is there, then it’s not there – it’s a phenomenon, it comes and goes.

Perception: as soon as we get onto the level of perception, we can see the way the mind is involved in creating it because the mind makes mistakes in perception. A slight stripy shadow in the bushes – it isn’t necessarily a tiger, but still the mind may perceive, “Tiger!” The mind makes mistakes in perception. We sometimes get confused between hot and cold – if we’ve had our hand in ice then put it in cool water it feels like it’s burning; perception can make mistakes like that. Perception is not properly reliable: it’s useful, very useful, essential, but it’s not properly reliable and there are no inherent truths in a perception – it’s what we make. Perception is empty.

As I discussed, impulse, habits, maybe you can see how empty they are; they’re simply arising out of causes and conditions – they’re not even necessarily accurately representing or relevant to the present moment; they’re just popping up unbidden, arising from the conditioning of past experiences.

Consciousness you might say, is giving a clear view of all of this stuff, but it’s giving a clear view of potentially inappropriate impulses and misperceptions, and mistaking transient sensations as indicating that something is there. Then the idea of the self. Mind is responsible for creating this mistaken idea of self; it imputes a self as a co-ordinator, as the connector, as the experiencer of all these miscellaneous phenomena. But the teaching is saying it’s not so, it’s empty.

It’s hard to grasp; it’s counterintuitive; it’s not even catered for in the structure of our language, in fact our language distorts such exploration. As soon as we start trying to talk about this stuff, we find ourselves using the word ‘I’, which we’re negating by saying there’s no self. Our language is built on subject/object and therefore that’s the language we have to use. But it doesn’t work for this exploration because we’re trying to use subject/object language to point out the lack of subject (and of object). Emptiness, emptiness of self, lack of subject in the subject/object. We can’t find the words to do that because they’re not in the language.

Emptiness in relation to other teachings

Let’s keep going: there is no form, and no sensation, perception, volition or consciousness. That sounds like another repetition, doesn’t it, and it is also a refutation of the idea that the five skandhas are the ultimate inherent objects; he’s giving us every opportunity to get it. Then it expands a bit – beyond that we get:

no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind;

no sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, thought;

and there is no realm of the eye all the way up to no realm of mental cognition.

What’s going on there? The list I’ve read out to you is the list in the teaching on the eighteen realms.

• We have the six senses. Sight, sound, smell, taste, touch are straight forward. We’re familiar with the five senses, and then in Buddhist literature we also have the sixth sense: thought, cognition – think of it in those terms.

• We have the six sense organs, one for each of those senses, which is why the preceding line says no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind. They also are empty – the sense organs, as well as the senses themselves.

• Then we have the six sense-consciousnesses: There is no realm of the eye all the way up to no realm of mental cognition: the resulting sense impression on the mind is called a sense-consciousness. This is saying, there is no eye-consciousness, no ear-consciousness, no nose- consciousness – that sort of meaning.

When it says there is no realm of the eye ‘all the way up to…’, it shortens the list for you by omitting some items and saying, ‘all the way up to’. This is because the lists are getting a bit long. We’ll encounter similar devices as we continue through this (and other) texts.

The abbreviation makes it even harder for us to follow unless we know what’s being abbreviated. In this case, it’s started to lay out the eighteen realms but not listed them all. Here we have another potential linguistic trap. When it says no this and no that it isn’t denying the phenomena of sense organs, sensory experience and so on, but it is declaring them as empty. It’s not only saying that sensation is empty, it’s saying specifically that all eighteen of the realms – six sense organs, six senses, and six sense-consciousnesses – are all empty.

It continues:

There is no ignorance and there is no ending of ignorance

through to no ageing and death and no ending of ageing and death

Do you recognise what’s going on there, what’s being negated there? Not all of you will, because it’s pointing to a specific teaching that you may not know: the twelve links of dependent origination. Unless you know the teaching on the twelve links of dependent origination, you’ve no idea that’s where this is pointing. It’s giving only the beginning and the end of the sequence of twelve links, ignorance and death, without the whole sequence in between.

If you know that teaching, then you’re hearing the negation of that teaching when you see those lines; you’re hearing the assertion of their emptiness. Maybe negation’s not quite the right word: assertion of emptiness of the twelve links in that teaching.

Next: There is no suffering (there’s that phrase you were waiting for, ‘no suffering’), no cause of suffering, no cessation of suffering, and no path. Most of you will recognise the teaching that’s being emptied out here. The Four Noble Truths, Buddha’s early teaching: there is suffering, there is a cause of suffering, there is the possibility of cessation of suffering, and there is a path, i.e. the Eightfold Path, to the cessation of suffering. That’s the conventional traditional teaching, but the Heart Sutra, the emptiness literature, is saying: there is no suffering, no cause of suffering, no cessation of suffering and no path. How can it say that? Well, with emptiness of self, who can there be to suffer? Without attachment to a sense of self, how could the word ‘suffering’ even have any meaning? But then, how can what I’m saying have any meaning to you given that you are so firmly attached to your sense of self. These teachings are very hard to receive.

Relying on Prajnaparamita

There is no wisdom, or any attainment.

With nothing to attain,

Bodhisattvas relying on Prajnaparamita

have no obstructions in their minds.

With no destination or attainment to be sought, how could there be obstructions? You haven’t got anywhere to go, you haven’t an idea of trying to get to somewhere; how could you be obstructed? Without any obstruction, how could there be fear of any failure, fear of missing out?

Bodhisattvas relying on Prajnaparamita, Prajnaparamita in this sense meaning the insight into emptiness: they have no obstructions in their minds, they have no fear.

departing far from confusion and imaginings

they reach Ultimate Nirvana

Not trapped in delusions, imaginings, confusions, because they’re not attached to them, because they see the emptiness of them; they’re merely passing phenomena, not to be attached to.

All past, present and future Buddhas

relying on Prajnaparamita,

attain Anuttara-Samyak-Sambodhi.

Unsurpassed, supreme enlightenment, through relying on Prajnaparamita, through gaining this insight of emptiness of all dharmas – emptiness of skandhas and of everything else. The emptiness of everything.

The Prajnaparamita mantra

And then we move on:

Therefore, know that Prajnaparamita

is the great mantra of power,

the great mantra of wisdom,

the supreme mantra,

the unequalled mantra,

which is able to remove all sufferings.

There’s a shift of gear here: are we suddenly into mantra territory rather than philosophy? Are we into magical actions removing all sufferings? A shift of gear here, and an assertion: it’s real and not false. On the other hand, taking Prajnaparamita, taking insight into emptiness as your mantra, as your constant companion, maybe that’s not such a bad thing: whatever situation you find yourself in, bring up your mantra, remind yourself to examine the dharmas. Bring up your insight into Prajnaparamita, your insight into the perfection of wisdom of emptiness. That, in any situation, removes all sufferings. Yes, it’s presented as a mantra, but it’s also truly promoting ongoing cultivation of the wisdom of emptiness. It’s quite interesting to look at it that way.

It is real and not false – in case you were doubting by this point, yes it’s real and not false.

Therefore recite the mantra of Prajnaparamita

The mantra of Prajnaparamita you know: Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha, translated as either ‘Gone’ or ‘Going’ – a little bit more active in ‘going’, but ‘Going, Going’ or ‘Gone, Gone, altogether Gone’ and ‘Gone totally beyond.’

Beyond what? One meaning of this is ‘the other shore’: you’ve gone beyond this shore of Samsara, which includes attachment to form and the other attributes of self, and you’ve gone to the other shore of Nirvana and release and enlightenment. But even that creates a duality, doesn’t it? It’s creating a duality between form and emptiness, between Samsara and Nirvana – regard that as simply an interpretation, a metaphor or presentation. But yes, ‘Gone, gone beyond,’ and then Bodhi meaning ‘enlightened, ‘awakened’, Svaha, ‘Hail, Celebrate’.

How to practise

That was a quick run through a rather complex text with a lot of short cuts and abbreviations, a lot of jargon. A lot of explanation, study, investigation and practice is needed to truly appreciate the depth of it. How does that relate to what we’re doing?

Indeed, we are like Avalokiteshvara. We are indeed examining the dharmas in deep meditation – that’s precisely what you’ve been doing; you’ve been noticing what arises in the mind, you’ve not been obstructing it or denying it, you’ve been letting it through, letting it arise, letting it be experienced. That experiencing of it is investigating it. We use the word ‘investigation’ here in the sense of an experiential investigation – it’s tasting, knowing first-hand, feeling, investigating. It’s not investigating by sitting back in an armchair and thinking about it with some textbooks at your elbow. You don’t need the books, you don’t need to be reading Prajnaparamita. You need to turn the gaze within, as instructed in On Pursuing That Which Leaves No Tracks.

All you have to do

This minute

is to stop –

turn the mind upon itself.

Then you won’t need to read the Heart Sutra; instead you’ll be in a position to write it, from your own experience.

Draw your sense within

Turn yourself inside out:

Gazing into the lake of awareness

Let what is there emerge from its lair.

I hope you’ve been doing that; it’s what we’ve been doing, isn’t it? We’ve been using a koan to seed the mind into an investigative mode, and turning that investigation on the mind: what is arising at this moment? Let it emerge from its lair.

‘Lair’ is a nice evocative word, isn’t it? What might come out of a lair? Could be a bit scary. I found a big hole in the hillside over there, a year or two ago: What on earth is living in that? I put my trail camera on it and went back and had a look the next day, and the camera had been tipped over – ooh! Try again, so I kept on. It took me a few days to get the picture. A hole about this big – I thought perhaps badgers or foxes, they are around but I don’t know where they’re living. On the recording all I saw was a tiny vole going in and out of the big hole!

But ‘lair’ can conjure up a bit more – and some of you have had the experience, even during this retreat, of something larger than a vole emerging from its lair. You can get shocks when you allow yourself to see what’s arising in the mind: ‘Oh, I wasn’t ready for that, but here it is!” Let what is there emerge from its lair is a very open and inclusive statement – it could be a little beetle, it could be a vole, it could be a rabbit, it could be a badger, or…

There’s a rabbit hole here, which my leg went down once. I didn’t know we had rabbits here. We see hares daily, but I’ve never seen a rabbit. I aimed a camera1 at that hole and what did I see on my camera? A few times I saw a badger come along and shove himself down into the hole, probably hoping for a rabbit supper. You wouldn’t believe the badger would fit but yes, the badger went down headfirst, leaving only his back legs and knees outside the hole to haul himself out again. He would come along every two or three nights and recheck the hole. What emerges from holes is interesting.

Let what is there

Invade your breathing.

Let what is there pulsate in your heart.

Let it be directly sensed, is what it’s saying – that’s exactly what you’re doing. When Avalokiteshvara directly sensed what he was perceiving in his meditation, he realised its emptiness. That possibility is directly open to you in this practice: stimulated by the koan, you bring a sharp attention to whatever’s arising in the mind. If you’re in the state of Great Doubt, you’ve got a desperation to solve it, and how can you solve it? Really, only by almost grasping anything that comes along, in case it’s your solution – you can’t risk it slipping by. Your practice may not be in that intense a situation, but still you’ve cultivated ‘I don’t get it; there’s something I’m missing. If something arises, it might be the missing piece; I can’t let it slip by unobserved.’ You’re open to it arising; you directly perceive it.

It might move around the mind and might take a few funny twists and turns; there might be some mental associations arise, things might come to mind – and all the while you’re sharply attentive because the koan has got you to that state of mind. At some point you might see behind or see through these phenomena that are arising in your mind and you will appreciate emptiness right there, in that moment. Give it a go.

Notes

1. https://youtu.be/cixw68zMkzU

Glossary of terms

- Chan (禪): Chinese pronunciation of Sanskrit "dhyana" (meditation); the Chinese school of Buddhism known as Zen in Japanese. Emphasizes direct insight and meditation practice.

- Compassion (慈悲, ci bei): Active care and concern for others' wellbeing; in Buddhism, the natural response arising from wisdom that sees interconnection.

- Dharma (法): The Buddha's teachings; truth; the way things are; Buddhist law and doctrine.

- Emptiness (空, kong / Skt: śūnyatā): Not nothingness, but the absence of independent, permanent, separate existence; all phenomena arise through causes and conditions.

- Huatou (話頭): "Head of thought" or "mind before thought"; Chan practice method of observing the mind before thought arises; the still mind.

- No-self (無我, wu wo / Skt: anātman): The Buddhist teaching that there is no permanent, unchanging, independent self; what we call "self" is a process of constantly changing conditions.

- Silent Illumination (默照, mo zhao): Chan meditation method emphasizing silent, open awareness without focusing on specific objects; developed by Master Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091-1157).

- Wisdom (智慧, zhi hui / Skt: prajñā): Direct insight into the nature of reality; in Buddhism, specifically the understanding of impermanence, no-self, and interdependence.

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2024 Dharma Talks Simon Child

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-547