Justice, Sustainability, and Participation

An Inaugural Lecture. The University of Bath. January 31st 2002[i]

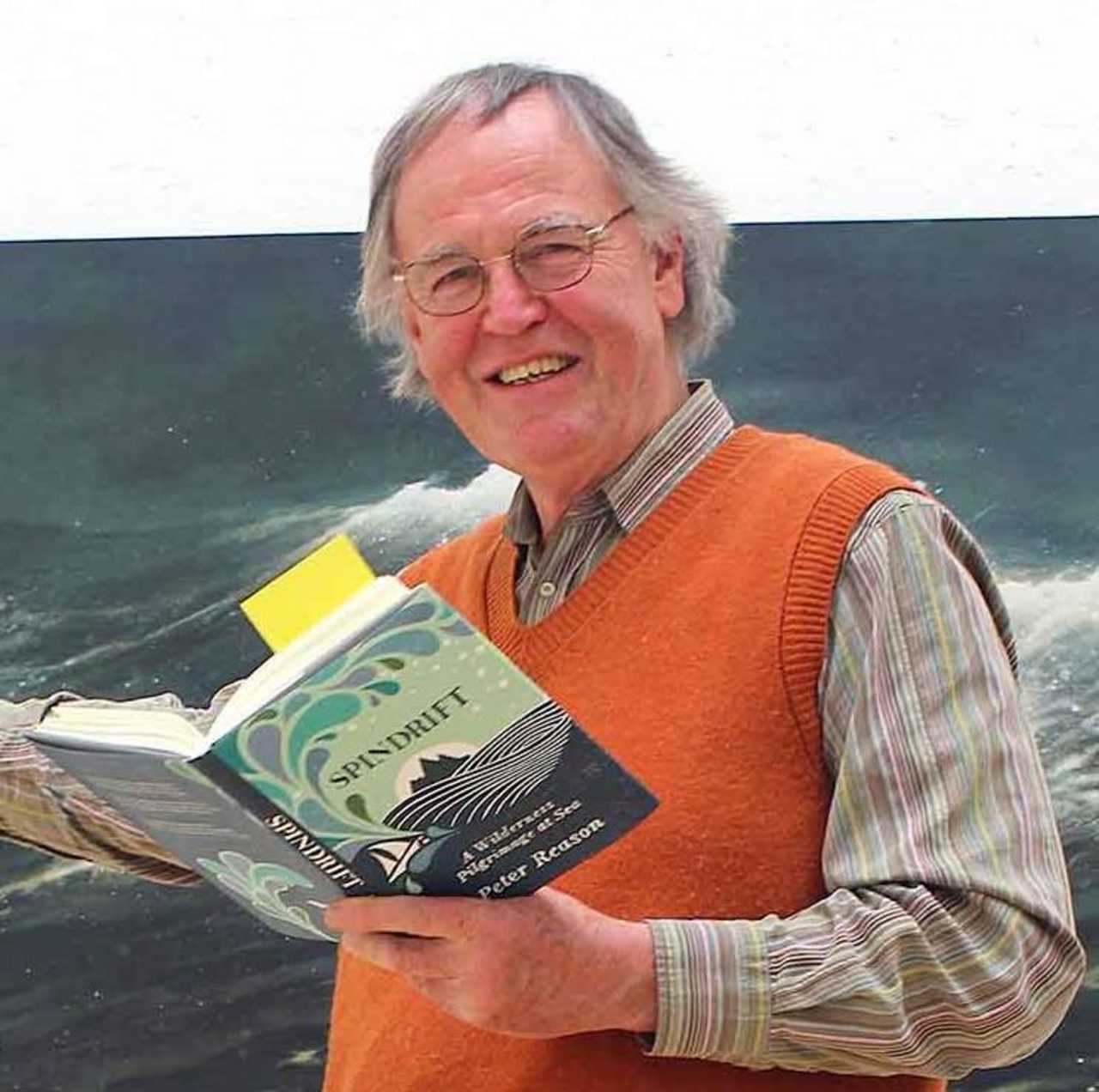

Professor Peter Reason

Centre for Action Research in Professional Practice School of Management. University of Bath

Peter Reason, in his bold inaugural lecture, provides a wide conspectus of problems surrounding justice in this post-modern world. He brings together numerous themes from contemporary culture to throw light on the koan that affects us all. As I read and re-read this generously spirited enquiry I am struck again and again by the parallels between its message and the fundamental realisation the Buddha – the law of co-dependent arising. In such writing as this we can foresee a modern renaissance of buddhistic teaching of great saving significance in our troubled world. We are grateful to Peter for allowing us to publish it here. (JHC. Ed)

A meditative beginning

Justice, sustainability and participation are three huge words. When I was asked for a title for this lecture I chose them quite easily as representing the themes of my work. As I have attempted to craft them into a lecture for this diverse audience I have found out how complex they are. I want to talk about the state of our world and the way our mind frames and understands that world. Let me start with a story.

Recently I went on a Buddhist meditation retreat in the Chinese Chan tradition[ii]. On this retreat, in addition to the usual meditation practice to calm and quieten our minds, we were invited to work with a koan. Koans, I learned, are short stories, usually of a paradoxical nature, that the trainee is invited to hold in the mind. Since the koan is essentially paradoxical, the point is not to solve it but to allow insights to arise as one watches the mind work with the koan. In the end, it is hoped, the paradox is cut through.

The koan I worked with goes like this:

"It was a hot, summer day, the windows and verandahs of the Chan hall were open to the surrounding lawns and trees. The Master climbed the pulpit and raised his fly whisk (hossu) to indicate he was about to give his sermon. At that moment a bird began to sing in the garden. The Master stood with his hossu motionless. The bird went on singing. Eventually the song ceased. The Master lowered his hossu. He said, " Oh monks, that will be all for today." and returned to his room."

Here we have an everyday story of monastery life, but it has resonances in our own culture. We are all startled from time to time from our everyday preoccupations by the sound of birdsong, by the sound of raindrops, or by the silence of snow. On Monday I was arrested, so to speak, by the sound of the hailstorm on the railway station roof. So what is this story about?

I sat in meditation with this story for seven days.

My first line of inquiry, which is linked to my theme of sustainability, is that the koan tells us that we can learn as much from the more than human world than from the wise words of the Masters. Christ told us to consider the lilies of the field. Meister Eckhart in the Christian Mystic tradition tells us that every creature is a word of God and a book about God (Fox, 1983:14). The Sufi poet Hafiz wrote (Hafiz, 1999:269), "Every being is God speaking. Why not be polite and listen to him?"

But what is the birdsong saying to us and how are we to listen? Let's go a little deeper.

The koan reminds me that today we have very little (consciously) to do with the 'other than human'. We live with other humans, with our own human-made technologies, with a human-made countryside yet we can scarcely see the stars. This is a precarious situation, for "We need that which is other than ourselves and our own creations. We are human only in contact, and conviviality, with that which is not human" (Abram, 1996:ix). And songbirds are in catastrophic decline, so this sweet story both masks and points toward the tragedy of the current loss of species.

We must, I thought, learn to listen to the wild. But the bird is not in the wild, it is singing in a cultivated garden; and is heard through the windows and verandahs of the Chan hall by monks waiting to hear a sermon. How can we hear the wild if its voice is so radically filtered through our own frames and perspectives, "through the windows of my mind", as Simon and Garfunkel put it. And more than that, I got more and more angry about the rigid roles portrayed in the koan, with this Master gesticulating with his hossu, and dismissing the monks in such a seemingly supercilious fashion. The koan showed me both the necessity and the impossibility of listening to the more than human world, the importance of openness and surprise, and at the same time how we are trapped within our minds and roles. I realised how important it is to walk on the margins of wilderness so as not to be trapped in single vision; and at the same time how fundamentally impossible this was. During the retreat these thoughts gave rise to despair, grief and rage about our human condition, in contrast to the sweet romanticism of the first stage of investigation.

Gradually, I exhausted all these possibilities. The koan ground my mind to a complete halt. There is no one solution, the koan contains all these possibilities, and more. So I stopped struggling to find a meaning and sat in meditation holding the koan more lightly, on the “back burner" as the teacher put it.

And I learned how meditation itself is a continual process of inquiry into mind. I learned how to bring my mind to some point of stillness, almost empty of thought, to notice each thought as it arose, almost like an eddy in calm waters, and then let it go. A delicate place, for if I didn't notice the eddy as it arose, it would soon become a whirlpool of thought that would develop a life of its own, suck me in away from my quiet mind. I think the low point came when I realised I had spent half an hour of zazen tracing in meticulous detail the wiring of the gas alarm on my boat. Yet at other times I was able to sit with my mind quite blissfully quiet, noticing each impulse as it arose. Meditation is a delicate, subtle, moment-by-moment inquiry into these processes of the mind. A delicate process of learning how to avoid one's mind being captured by its own frames and, as such, it is a training for an inquiring life.

And I realised it is only through this kind of inquiry that the koan can be resolved. So in the koan the monks can respond to the birdsong in many ways: they may be bored, they may be angry that the Master doesn't give a proper sermon, or they may think they know what he means and what message the bird is bringing. Or they may be able to notice both the immediacy of the birdsong and the framing mind at the same time. The only adequate response is one of inquiry: What is it? What is this about? What is my response? Where does it come from? Am I awake to all these possibilities? How am I and the bird and the whole context together co-creating this moment? This is about bringing our moment-to-moment inquiring attention into more and more of our lives as we live them. Not easy, not fully possible, but equally essential if we are not to be living asleep. This attitude is not limited to Buddhism. It is fundamental to our practice of action research: "living life as inquiry" as my colleague Judi Marshall puts it (1999). Meditation retreats are one way of training the mind for this kind of attention.

Richard Rorty suggests that the function of the liberal intellectual is to instil doubts in students minds about their own self-images and about the society to which they belong (1999:127). We don't do this very well. One of my students wrote recently about how difficult it was to write reflectively as she realised that the western world-view was embedded in her mindset:

"From my experience, essay writing is mostly a regurgitation of the relevant facts and theory, presented in a logical, coherent order. As undergraduates, we are generally required to cite other people's opinions without actively engaging with them and expressing a personal view. Writing in the first person is certainly an unusual and exciting experience. This provides an ironic contrast to the much-avowed principles of freedom of inquiry and discourse within academic institutions. $£$£As I approach the end of my studies, I can't help feeling that freedom is a fallacy, and that somehow I have been walking a predetermined path to mortgage repayments and commuting nightmares. Further, I'm not alone. Despite a whole array of "graduate opportunities" there is a growing mood of claustrophobia and sense of powerlessness; for all the relative luxuries of the western world, we are still unsatisfied; there is an unmistakable sense of longing, a deep craving for some kind of release or escape." (Sarah Atkins, 2001)

What is it that this bright young woman, and at least some of her contemporaries, wants to escape from? I want to suggest to you that it is from the all-encompassing frame of the modern worldview, which stops us listening to the world. It is a way of doing and being in the world which has made extraordinary contributions to human affairs in the flourishing of culture, scientific endeavour and material well being, and has brought in its wake human alienation, ecological devastation, and spiritual impoverishment. In particular it has brought the twin global crises of justice and sustainability. I want to suggest to you that these two crises represent an enormous challenge, and one that cannot be fully addressed within the modern worldview because it is that worldview that has substantially brought about these crises.

In very simple terms I want to articulate a dreadful warning: we cannot go on the way we have been doing based on the way we have been thinking. And I want to offer a challenge, an expression of hope for a way forward based on a participatory ethos. I want to explore how a worldview based on the experience of ourselves as participants in the processes of life on earth might provide a more fruitful perspective.

In taking on these big words I am entering territory on which we all have an opinion: I don't expect to get it right, I don't expect you to agree with me all the time. Some of what I say will be contentious, so some of what I say may seem obvious to you, and maybe some of it absurd. There are inevitably gaps in my argument. But I do know that these are issues we don't talk about enough and ignore at our peril.

In search for a participative worldview

When I talk about a worldview, I am talking about the fundamental basis of our perceiving, thinking, valuing and acting, "the windows of our minds" through which we hear the birdsong.

Every society has always rested on some largely tacit, basic assumptions about who we are, what kind of universe we live in and what is ultimately important to us (Harman, 1988)

The worldview of a culture changes from time to time; the shifts from the medieval to the Renaissance to the modern worlds all rest on deep stirrings and intuitions which give a new picture of the cosmos and the nature of being human. Our worldviews are not simply rational things, they are about the mood of the times, the metaphors we use without knowing we are using them, the spirit of the times. A worldview encompasses our total sense of who we are, what the world is, how we know it. It encompasses our sense of what is worthwhile and important, what are the moral goods to pursue. It guides our sense of the aesthetic and the spiritual. And it is the basis of our social organisation and political, personal, professional and craft practices.

The notion that the Western worldview may be currently in revolutionary transition has been part of intellectual currency for quite a while. This worldview was formed some 3-400 years ago in the period we know as the Enlightenment. The older medieval, Christian worldview portrayed a world whose purpose was the glorification of a transcendental God. Bacon broke with this, making the link between knowledge and power, and told us to study nature empirically. Galileo told us that nature was open to our gaze if we understood that it was written in the language of mathematics. Descartes' 'cogito ergo sum' made a radical separation between the human and other modes of being; and Newton revealed the universe as a determinate machine obeying causal laws.

Our worldview channels our thinking and perception in two important ways. It tells us that that the world is made of separate things. These objects of nature are composed of inert matter, and operate according to causal laws. They have no subjectivity, consciousness or intelligence, no intrinsic purpose, value and meaning. And it tells us that mind and physical reality are separate. Humans, and humans alone, have the capacity for rational thought and action and for understanding and giving meaning to the world. This split between humanity and nature, and the abrogation of all mind to humans, was what Weber meant by the disenchantment of the world.

The disenchantment of the world is also the disenchantment of the human person, which the modern worldview sees as autonomous, individual, calculating homo economicus, separate not only from the natural world but from our fellow humans. Margaret Thatcher both captured and showed the absurdity of this in her infamous statement that there is no such thing as society, only individuals.

Of course I oversimplify. A worldview is never so monolithic, so without contradictions, that it can be so briefly sketched. But stay with me in this inquiry, for despite exceptions, this official worldview runs much of our lives.

And of course in many ways these developments have been hugely valuable. For better or worse, we are clearly attached to the apparent comforts and benefits of modern life generated by the genius of scientific investigation.

But at the same time, there are all around us hints that this modern worldview has reached the end of its useful life. This is, I believe, partly because it has strained the limits of what it can encompass, as do all worldviews, and partly because it works in the service of the privileged of this world, against the interests of the poor and powerless.

So what are the origins of the modern worldview?

The philosopher Stephen Toulmin argues (1990) that the perspective of the Enlightenment should not be seen as the first break with medieval thinking. Rather, this break with the Middle Ages occurred considerably earlier, with the Renaissance humanists in late 16th century Northern Europe, men like Michel de Montaigne, Shakespeare, Machiavelli. They were sceptical about the relevance of theory for human experience, more interested in the concrete, the particular and the practical. They argued for a trust in experience, the courage to observe and reflect, a curiosity about the diversity of human nature.

During the 17th century these humanist insights were lost. There was a historical shift from a practical philosophy based on experience and particular practical cases to a theoretical, more metaphysical philosophy concerned with the general, the timeless, and the universal. The philosophies of the Enlightenment were based in a quest for one essentialist truth and a certainty. The shift was fuelled by the extraordinary perils and tragedies of that age, for the old cosmopolis, the political and intellectual order, was falling apart. As John Donne wrote about that time:

‘Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone’

which bears an uncanny resemblance to Yeats:

'Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold'.

Now why did this happen? One indication is the assassination of Henri IV of France in 1610. He had tried to decouple nationalist loyalty from religious affiliation, and his violent death was a sign that tolerance between Catholic and Protestants was not a political possibility. European monarchs picked sides in the name of religious loyalty, and Europe was devastated by the dogmatic religious struggles of the Thirty Years War. The bloodshed was appalling as religious armies marched to and fro across the 'gladiatorial ring' of Germany and Bohemia, essentially in an attempt to win the religious and intellectual argument by force of arms, which of course proved impossible. Toulmin argues that this brought about a 'counter-Renaissance', a demand for a new certainty in the face of these appalling crises which neither humanistic scepticism nor religious dogma seemed able to meet. Thus the quest for certainty, which led to the philosophy of Descartes and mathematical kinds of 'rational' certainty and proof, should not be seen as a philosophical advance out of its political context, but as a timely response to a specific historical challenge - the political, social and theological chaos embodied in the Thirty Years War. (1990:70)

Toulmin continues the story to the present time. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, as different sciences developed, a more pragmatic attitude developed: each new discipline had to discover its own methodology, and the hard edges of Enlightenment rationalism were softened. But just as Europe was beginning to rediscover the values of Renaissance humanism in the early 20th century, the roof fell in with the First World War, the inequitable peace and the Great Depression. Re-renaissance was deferred and there was another push toward abstract certainty with the intellectual monopoly of logical positivism, reflected in abstract art (Gablik, 1991) and Le Corbusier's proposition that a house is a machine for living in. It was not until the 1960s that humanism could be re-invented and we could begin to return to more practical philosophies. We are beginning to see that 'Ignorance is not a solvable problem, it is an inescapable part of the human condition'. (Orr, 1994:9).

Toulmin's story shows how the philosophical vision of the Enlightenment, the emphasis on rational knowledge and transcendental truth, was fuelled and amplified by the political circumstance of that time- primarily the bloodbath in Western Europe that was the 30 years war. If the politics of the Eighteenth century were bloody, the political issues of our current times are every bit as significant, challenging and dare I say frightening.

Underneath the blanket of our incredibly prosperous global capitalism, underneath the assumptions of peace and liberty, are huge uncertainties. These have been drawn to our attention by the terrorist acts of September 11, but in many ways this overshadows and maybe obscures the underlying issues: the crisis of sustainability and the crisis of justice and poverty. These are the major problems or challenges to which confront humanity in current times. They will not respond to solutions within the mechanical worldview, but demand of us new ways of thinking and new political structures a 'new cosmopolis' based, I believe, on inquiring participation.

I believe that an ethos of participation could be a new basis for our sense of who we are in this world, for our ways of understanding and knowing each other and the more than human world, for a guide for practice, and indeed as an aesthetic and spiritual principle. In this sense I see a participatory sentiment as emerging in contrast to the largely mechanical metaphor of the world of modernism in which we all grew up.

Let me start with showing that in order to truly understand the crisis of sustainability we must experience ourselves as participants in the planet's life systems.

Gaia

The crisis of sustainability demands that we think again about the nature of our planet and the biosphere which sustains us. The modern worldview makes a clear distinction between rational, thinking, humans and a non-human world devoid of intelligence, determined by chance and necessity. But there is another view which sees planet earth as a self-organising whole, metaphorically a 'living' being. This is Gaia theory, which the philosopher Mary Midgley refers to as the 'next big idea' (2001). Gaia theory derives from scientific inquiry into the systemic, interconnected nature of the planetary systems. It is also a rediscovery of anima mundi, the soul of the world; an idea, says Midgley, which is big enough to reunite science and spirituality, to give us an appreciation of how the Earth and her inhabitants matter in themselves, regardless of any use we humans might wish to put them to.

The origins of Gaia theory go back to James Lovelock's work for NASA in the 1960s. Lovelock, a Fellow of the Royal Society, was known in those days for his work on instrumentation. It was he who invented the electron capture detector which demonstrated the build up of DDT in the biosphere and of fluorocarbons in the ozone layer. He was also employed by NASA to develop equipment to be landed on the planet Mars in order to detect the existence of life. As he thought about how to do this, he realized that one could tell whether there was life on Mars without ever sending a spaceship there, by looking at the chemical composition of the Martian atmosphere. The Martian atmosphere is 95% carbon dioxide; in contrast the Earth's atmosphere is 21% oxygen and 77% nitrogen. So the Martian atmosphere is at chemical equilibrium; all possible chemical reactions have taken place, and there is not much going on there; while the Earth’s atmosphere is far from equilibrium with large quantities of oxygen, a highly interactive gas. Something is going on here on earth other than simple chemical interaction to hold the atmosphere at this statistically improbable state. Lovelock concluded that it was the interaction between living things and the earthly environment which not only made Earth's atmosphere but also regulated it, keeping it as a composition favourable for life over billions of years.

In the 1960s and 70s this was far from the conventional paradigm. The non-living world of rock, atmosphere and ocean were seen to determine key variables for life. Living things must adapt to these conditions or die. In this view, life is allowed no major influence on the non-living world.

Gaia theory proposes two radical departures from convention. The first is that life profoundly affects the non-living environment, such as the composition of the atmosphere, and this then feeds back to influence the entirety of the living world. Gaia theorists talk about a tight coupling between living and non-living worlds. The second proposal is that out of this tight coupling between life and non-life comes an unexpected property, the ability of Gaia, of the Earth system as a whole, to maintain key aspects of global environment, such as global temperature, at levels favourable for life, despite shocks and disturbances from both within and outside itself. (Harding, 2001:17)

“Gaia” is a way of describing Earth as an interconnected whole with emergent properties of self-regulation. Let me briefly take the example of the carbon cycle. Carbon dioxide pours out of planet earth in volcanoes. As you will know, carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, and so if too much were accumulated the planet would get too hot. The Gaia self-regulating system locks up carbon at such a rate as to maintain temperature within appropriate limits. The weathering of granite rock allows calcium ions to escape and combine with rainfall and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to make calcium bicarbonate. This is washed down to the sea and used by algae called cocolithophores to create their shells, which, as they die, sink to the seabed to form layers of chalk. So when you see the white cliffs of Dover you are looking at carbon deposits. And when you see a granite rock you are looking at something which participates in the processes of life on earth.

When the temperature of the planet increases, these chemical reactions speed up, so providing a feedback loop to increase the sequestering of carbon dioxide; and as temperature cools, the reactions slow down. But it has also been shown that these purely physical and chemical reactions are not sufficient to explain how the temperature has stayed at a level suitable for life all these millions of years. Life comes into the picture by increasing the weathering of rock in many ways, so that the calcium ions are more available for the link with the carbon. The roots of trees crack open the rock, bacteria secrete compounds and lichens release acids, all of which accelerate chemical weathering, and again take place faster at higher temperatures, providing further self-regulating feedback. Life participates fully in the creation and maintenance of its own environment.

Again I oversimplify, but the story is correct in its essentials. Much careful research has been conducted to show many other ways in which the life processes are central to the maintenance of the steady state of Earth's temperatures and other essential qualities of the biosphere. All of these can be seen and understood from a lay perspective in Lovelocks books (1979) and Stephan Harding’s articles in Resurgence (e.g. 2001). The point for my current argument is that Gaia theory shows that there is an intimate and complex connection between life on earth and the self-regulating properties of Gaia, that the whole planetary system is an intricate, self-sustaining and self-organising web of life.

So what is happening to this web of life, and in particular what is happening to the carbon cycle? We humans of the industrialized North, through burning carbon fuels, are releasing the carbon which has been locked up in deposits for millennia and we are doing so at an increasing rate. At the same time we are damaging the planets capacity for self-regulation by, for example, cutting down the forests. As we pursue our short term interests (and in Gaian terms a century is less than a blink of an eyelid) we are cutting through the self-regulatory cycles and causing an upsurge in planetary temperature with the accompanying disturbances to the weather system.

Whatever President Bush and his contrarian advisors may think, this is no longer in doubt. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a body of scientists brought together by the UN to inform governments on the likely causes and consequence of climate change, has been looking at the evidence for the past 12 years. Their third report confirms that global warming is occurring, is largely brought about by human actions, and will increase far faster than previously thought. Carbon dioxide is up 31% from its level in 1750; Earth has lost 10% of snow cover since the 1960s; glaciers are retreating and the Arctic sea has thinned by 40% since the 1950s; all these trends are accelerating. If we go on as we are at present, global temperatures will rise by 5.8°C over the next 100 years. If we use less carbon-based energy, temperatures will only increase by 1.4°C over the same period (which is bad enough). But we are currently embarked on the more extreme scenario. These forecasts do not account for interaction effects between the biosphere and the atmosphere, for example the way in which melting permafrost will release methane into the atmosphere. It was reported at the January meeting of the Royal Geographic Society that Europe's great rivers the Rhine, the Rhone, the Po and the Inn are expected to run dry in summer months in 20-30 years time because the glaciers in the Alps which feed them are melting. Consider that!

The pattern of disturbance which we see in global warming is repeated in many aspects of the life of our planet: the poisoning of the water, the loss of topsoil, the destruction of forest, the devastation of fisheries. We are currently seeing the sixth great extinction of the life on the planet, the greatest and fastest ever, according to Lord May, President of the Royal Society (see also Leakey & Lewin, 1995), and it is caused by human activity. ALL living systems are in decline. It' s that simple. As Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute puts it, "The economic policies that have yielded the extraordinary growth in the world economy are the same ones that are destroying its support systems”. (Brown, 2001:7)

We well know that humanity and the natural world are on a collision course. And yet I can still read in the Observer a travel feature (in the section headed Escape, presumably with no irony) by Ann Widdecombe about her cruise to the Norways Arctic Wilderness. As she eulogises about the beauty of the places she visits, she remarks that "This is scenery on which man has left no mark". Sorry, Miss Widdecombe, the ice is contaminated with heavy metals, the fish stocks are collapsing, the ice floes and permafrost are melting fast, the polar bear is starving and well on the way to extinction. Humanity is having an impact on the biosphere of macroscopic proportions, while our consciousness remains relatively small scale. As Tom Berry puts it:

"The deepest cause of the present devastation is found in a mode of consciousness that has established a radical discontinuity between humans and other modes of being and the bestowal of all rights on the humans. The other-than-human modes of being are seen as having no rights. They have reality and value only through their use by the human, In this context the other than human becomes totally vulnerable to exploitation by the human " (Berry, 1999:4)

Ecological Dimension

The Gaia story shows us how the planet is a deeply interconnected living system, the mother of life on earth, if you wish. It places these dreadful statistics in an intellectual and spiritual framework which makes sense of global warming and other phenomena. Gaia theory shows us that the damage that is being done to the planet's ecosystems and the resultant sustainability crisis has its origins in our failure to appreciate the systemic nature of the planet's ecosystems, and humanity's participation in natural processes. Participation is an ecological imperative. The great systems thinker Gregory Bateson argued that that self-organising and self-maintaining ecosystems, with their intricate feedback loops and their capacity for dynamic equilibrium must be understood not as mechanical, but as expressing a form of Mind; not the autonomous self-awareness of the human mind, but a larger ecology of mind (1972) . Human conscious purpose, as we go about our day-to-day lives, can only comprehend a minute arc of this complexity, and so cuts through the circuits of this larger ‘mind’ which hold and preserve the stability of the biosphere of which we are a part.

Bateson describes the modernist view of the world and its consequences in graphic terms:

“If you have the idea that you are [outside of creation], you will logically and naturally see yourself as outside and against the things around you. And as you arrogate all mind to yourself, you will see the world around you as mindless and therefore as not entitled to moral or ethical consideration. The environment will be yours to exploit.

If this is your estimate of your relation to nature and you have an advanced technology, your likelihood of survival will be that of a snowball in hell. You will die either of the toxic by-products of your own hate, or, simply, of over population and over-grazing”. (Bateson, 1972:462)

It seems to me quite simple: unless we learn to experience ourselves as part of the biosphere, and understand that we are participants in a wider community of beings, the damage we will do to the Gaian systems will continue to be devastating.

Ontological dimension

So it is not just our reality that is participative, but the cosmos itself that is a participatory process. The process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead taught that the basic unit of being is not a thing but an event: the reality is the process. (Whitehead, 1926:90). And indeed, this is close to the Buddha's view of co-dependent arising. (Macy, 1991).

For many years I had a lot of difficulty with this idea, for it seemed to me self-evident that the world is made of separate things -- just look around you, it is common sense!

Let me be clear about the depth of the transition I am seeking to articulate. It is not a case of being nice and kind to the environment within a participatory worldview. This is non-sense, for the very notion of ‘the environment' already separates us from the world to which we belong. Rather our relationship to the Earth is that of a leaf to a tree. We have no independent existence. No tree, no leaf. Gaia theory shows us that we are participants in this planetary system, for good or for ill. It shows us what we are doing, and I believe, shows us that we must create a way of being which moves from the present devastating influence on earth to a benign presence, a presence that lives with the planetary systems rather than against them.

One way of doing this has been articulated by writers such as Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins and David Korten, processes they describe as the ‘ecology' of commerce, and Natural Capitalism. The idea here is that we must redesign our industrial processes so that they increasingly mimic those of the natural world, so that we run our affairs entirely from solar income, the waste of one process becomes the food for the next, and we work to increase, rather than decrease, the diversity of all ecosystems. (Hawken, 1993; Hawken, Lovins, & Lovins, 1999; Korten, 1999). We might call this ecological design intelligence (Orr, 1994:2), designing for participation in the cycles of the planet.

Justice

I think the story of the discovery of Gaia and the stories about Gaian self-regulation are wonderful stories. I find the idea that we are participants in a cosmic process, rather than disembodied minds trying to understand a deterministic universe, inspiring - even though the state of the biosphere is alarming. But when we look around the world we also see poverty, terror of many sorts, cruelty and injustice. I am not sure if there is a ‘good story' to tell about poverty and injustice.

Jean Niyonzima is a student on our current MSc Programme in Responsibility and Business Practice. He comes from Africa, and keeps telling us we in the North simply don't begin to understand poverty. I am sure he is right.

The picture is stark; really one statistic is sufficient:

- The richest 20% of world population share 82% of world income. o The poorest 20% of world population share 1.4% of world income.

- The richest 50 million people, mainly in Europe and N America, have the same income as 2.7 billion poor people. The slice of the cake taken by 1% is the same as that allowed to the poorest 57%. (Larry Elliott, Guardian 21-1-2002)

And of course the richest 20% cause the vast majority of the problems for the Gaian systems I have just discussed. The inhabitants of the industrialised countries constitute only one fifth of the world population but consume per inhabitant nearly 9 times more energy of commercial origin (mainly carbon based) than the inhabitants for developing countries.

Richard Rorty puts the moral problem rather well:

“We should raise our children to find it intolerable that we who sit behind desks and punch keyboards are paid 10 times as much as those people who get their hands dirty cleaning our toilets and 100 times as much as those who fabricate our keyboards in the third world. Social justice is the only basis for a worthwhile human life”. (Rorty, 1999:203-4)

Bill Clinton covered this area well recently in his Dimbleby Lecture, and I strongly recommend those of you who missed it to get the text from the BBC website. I think he got it half right, which is a great achievement for a politician. He and some other leading politicians have argued that this is not only unjust, it is unsustainable, it creates the rage and alienation that leads to terrorism, and that we in the richer North must in some way ‘help' the poorer nations through debt relief and more direct means. There is call for some kind of Marshall Plan. I am sure I was not alone in being encouraged by Tony Blair's Labour Party speech and Bill Clinton's Dimbleby lecture, and probably not alone in regretting the gap between speech and action. We have a duty to help them act on these insights as well as talk about them. But in another sense their ideas are still rooted in a perspective that many see are partly creating the problems they seek to address.

The orthodox economic view (Jay 2000) argues that the economic growth fuelled by globalisation, combined with greater equality and justice will raise the living standards of the poor throughout the world and indeed that it is already doing so. Surely, this is not entirely wrong, but it ignores a wider problem of participation.

Many voices from the South see the processes of globalisation, fuelled by a modernist western worldview, as contributing to both damaging ecosystems and creating poverty around the planet. Vandana Shiva tells us that:

“Poverty is the creation of a worldview that has pitted people against nature. That worldview has defined scarcity as the condition of nature, and has then tried to create technologies that are supposed to compensate for that scarcity. But the reality is that these technologies actually create scarcity because they destroy the environment, they destroy ecosystems, and they leave people poorer”. (Shiva, 2000:17)

For example, the sea has given enough to fisherfolk for centuries. But new technologies have been generated: trawlers so huge that they can take twelve jumbo jets in the trawl net.

They scrape the entire sea floor, catching everything that comes in their way, disrupting cycles of regeneration. Ninety percent of the fisheries of the world are near collapse. There is not much left to catch. The fisherfolk of India become poorer as a result of these technologies, which were meant to remove poverty.

This is true also of West Africa, where the EU has negotiated fishing rights with governments which ignore the rights of traditional fisherfolk, who have to go further and further to catch food and are in danger of being run down by huge European fishing boats. Our economic processes are part of the wider system of Gaia, and as we impoverish one we impoverish the other.

Participation is at the core of what we call political democracy at all levels of society. And it is encouraging to see that despite setbacks more people now are living under some kind of democratic political system than ever before, although political and legal democracy at a world level is in its infancy. And when you listen to voices from countries of the South you realise how much we pay lip service to democracy and how little we actually do to support it. We are interdependent with other humans in this world.

Participation is also at the core of economic democracy. As James Robertson points out, political democracy has been firmly on the agenda for 200 years and more, while economic democracy has been virtually non-existent (contribution in Reason & Torbert 2001). Indeed, it is arguable that capitalism works by a process of enclosure, privatising what was held in common, in the interests of the relatively few. We started in the UK with the enclosure of the commons for sheep farming and continued it in the Empire. We are now trying to enclose the patterns of life through gene patenting. We need to find ways in which people all around the world can share fairly in decisions that affect them and to share in the commonwealth of the planet as well.

I believe it is well argued that globalisation continues the process of enclosing the commons and thus dispossessing and disempowering people. Who asked the people of West African if it would be a good idea to allow the EU fishing boats in? We have no means of accounting for the externalities of global business, the costs imposed on the commons by the activities of the powerful. The argument that our current economic practices exacerbate poverty needs to be taken seriously: Economic structures disempower people; they suck wealth out of developing regions into the centre. Participation is thus the basis for a new economic order. This is the message of the anti-globalisation movement, and the message of the ‘new economics movement’. Contrary to the dismissive view of our leading politicians, this approach offers concrete suggestions for changes in tax structure, in accounting processes, and in different forms of money and finance that would bring about a decentralising, multi-level and multi-centred global economy. (see e.g. Robertson 1998) This would be more just and less damaging. My point is, briefly, that we will only see justice as we empower people through more participative decision processes and a participative economy both locally and globally.

Aesthetic and spiritual dimensions of participation

When I spoke of Gaia theory I suggested it can encompass both a scientific and a spiritual dimension. For some, this may be a step to far, but I believe it is a crucial one. The shift from a mechanistic to a participative frame is not just about the nature of knowledge, not just about bio-geo-physical feedback processes, not just about power, politics, economics and development. It is about seeing ourselves as members of a community of beings, of understanding, yes, the importance of humans, all humans in the scheme of things, but also frogs, ants, oaks and oceans. This calls for a transformation which is aesthetic and spiritual. As Tom Berry told me, without this kind of transformation we won't have the psychic energy to make the other, maybe more practical changes.

Aesthetic dimension

As part of our exploration of ecological thinking and experience, we take the MSc in Responsibility and Business Practice on a day long eco-hike down the river Dart in Devon, scrambling over rocks and under branches through one of the last pieces of wild nature in England. And along the walk we invite them to undertake some experiential exercises or meditations to get closer to the direct experience of the ecology. In one of these meditations we imaginatively identify with a part of the more than human world, and see if we can experience how it partakes in the cycles of Gaia.

The last time we did this, I was sitting against a tree in a particularly lush and damp piece of woodland. I relaxed against the tree, experienced my body against the wood and the earth, and looked around me. As I quietened my thoughts, and looked at those beings I call trees, earth, stones, birds and opened my imagination to include fungi, insects, bacteria, and then the various chemical substances, the elements and molecules and then again the quantum reality of the particles that lie underneath even that I realised everything I could see and imagine was in the process of becoming something else, that everything was participating in everything else. I realised quite suddenly that to see the world as separate things or beings was to have already abstracted from this ongoing process of being. And I think I understand what Whitehead and the Buddha might have meant.

Such meditations help us to realise the following:

- The experience of deep ecology is a feeling of joy and awe at the beauty of the more-than-human world.

- It is an appreciation of the delicate balance between chaos and order.

- It is the acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of all living beings, including ourselves, in the endless cycles of the planet.

- The experience is both of the moment and of eternity.

- It is the feeling of homecoming.

These, I suggest to you, are aesthetic qualities. We fully grasp our participation in the world through our appreciation of beauty; we open our eyes to frost on the ground, the buds on a tree, and we are struck by wonder. Through awe, wonder and beauty we can experience our sense of belonging, that we are a part of the whole.

Spiritual dimension

Participative consciousness is part of a re-sacralization of the world, a re-enchantment of the world (Berman, 1981; Berry, 1988; Skolimowski, 1993). Re-enchantment doesn't mean going back to a view of a world crudely populated by spirits. It is based in reverence, in awe and love for creation, valuing it for its own sake, in its own right as a living presence. To deny participation not only offends against human justice, not only leads to errors in epistemology, not only strains the limits of the natural world, but is also troublesome for human souls and for the anima mundi. This is the spiritual dimension of participation, to experience the world we live in and are part of as a sacred place.

And while a participatory vision sees the planet in a spiritual light, so it also sees the human, as nature rendered self-aware and self-conscious:

“The human activates the most profound dimension of the universe, its capacity to reflect on and celebrate itself in conscious self-awareness”. (Berry, 1999:132)

In this view, we are the universe looking at itself, consciously learning about itself.

Toward a participatory world

My proposal is that our world is in crisis (political, economic, moral and ecological), and that this crisis is, in the end, a crisis of worldview. Old patterns of thought and old institutions, the old cosmopolis, no longer responds to the challenge of our time. We need to explore how the modern world view, which divides self from other, mind from matter, humans from nature, which disenchants our world and our relationships with each other, can give way to a worldview in which we see ourselves as participants in the processes of human and more-than-human life on this planet. It is as if we are sitting in a meditation hall, and the even though the Master is drawing our attention to it, we are unable to hear the voice of otherness, the poor and the planet, through the windows of our collective mind.

The shift we seek is from control to participation as a way of being in our world (Goodwin, 1999). Participation, as I have tried to show, gives us a very different understanding of the world with live in, the wider cosmos, and how we come to know it. It throws a different light on the crisis of sustainability. In immediate practical human terms it is about human rights, power and politics, about how we create democratic human institutions in all fields. And in the end, because participation is intimately bound up with our sense of meaning and purpose, it also has aesthetic and spiritual dimensions.

We are faced with a challenge: will we again seek an illusory certainty, as we did at the time of the Enlightenment, after the First World War, pulling in further to reinforce old patterns of control? Or will we find ways to open ourselves to a participatory view of our world, with all the creative uncertainties that brings about? I believe only such a participatory vision will be adequate for the challenge of our times. And that challenge is immense.

The challenge is to use our human capacity for inquiry, our rational, empirical, intuitive, and aesthetic ways of knowing, and our sense that we are participants with one another and with all beings on the planet, so that human, conscious purpose designs processes which fit in with, match, even help restore the cycles of Gaia. We can meet our needs without destroying our life support systems. Creating a just and sustainable political economy would be inspiring, challenging and fun. But it is going to require a different vision, and a great deal more creative attention than we are giving it at the moment.

Not that it will be a straightforward process, however much we would wish we could easily solve the problems we have created for ourselves. The certainty the Enlightenment project offered proved to be a chimera. For the current world situation is paradoxical, almost koanlike. There is no way we can restore the diversity of species. Whatever we do, global temperatures are going to increase uncomfortably. We have to sit with what we have spoiled. And yet we have also to act, always inadequately, but hopefully with more ecological wisdom than we have so far.

We are beginning on both these fronts. Poverty and justice are a little higher on the global agenda, and we are beginning also to address the harm done by our carbon-based way of life through the negotiations of the Kyoto agreement and other initiatives. But this is painfully slow and limited by our current perspective on the environment as something we need to protect. What would bolder and more radical initiatives, ones more likely to meet the challenge of these times, look like?

National Level

Suppose, for example, that the current Government, which for all its faults is more environmentally aware than many, were to initiate a national debate to explore how the United Kingdom could become a decentralised carbon-free economy and reinvent ourselves as a sustainable society within ten years? I believe that the technologies to do this are present (in conservation design, in fuel cells, in renewable energy, photovoltaic cells etc), it just needs the political and cultural will. Just think where we would be if we had put all the investment in nuclear energy into renewables over the past 50 years! Imagine the ways in which this long-term policy could be a stir for creativity, for new industries, for new forms of investment, for both large-scale industry and the regeneration of impoverished communities. Imagine the potential for making new links, new forms of participation between the technologies of the information revolution and the Gaian dynamics of the solar economy on which we all depend. Imagine further the inspiration this might give us as a national community, the possibility of new worthy purposes around which we might gather, the new dialogues we might have together, the sense of meaning this might engender. Imagine how this might divert us from the petty controversies in which we indulge ourselves at present. Imagine the possibilities for new technologies, new exports, new forms of wealth creation that do not damage planetary systems. Imagine the example we might set to the world.

Individual level

And what can each one of us do? Wake up! Take these issues seriously. David Korten points out that the world is ruled by institutions that depend for their power on our forgetfulness, waking up is a revolutionary act (1999:16). Use your democratic voice and consumer power to resist processes that degrade the environment and exploit other humans. Raise your own awareness and talk about these issues with other people so we change the climate of opinion, together. And go and find a little bit of wild world every day and wonder at it.

We cannot continue to deny the gravity of the human situation; yet to revise our view so that we experience ourselves fully as participants on this planet and with each other provides for new inspirations. In the end, we have no choice but to engage with these issues, sooner or later. If we do so sooner we can do so with more dignity and more hope. Perhaps we may solve the most pressing living Koan of our time.

Footnotes

[i] This article is also appearing in “Concepts and Transformation” 2002. 7.(1). 7-29.

[ii] The Koan Retreat at the Maenllwyd. January 2002

References

Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: perception and language in a more than human world. New York: Pantheon.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. San Francisco: Chandler.

Berry, T. (1999). The Great Work: our way into the future. New York: Bell Tower.

Brown, L. R. (2001). Eco-Economy: Building an economy for the earth. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Fox, M. (1983). Meditations with Meister Eckhart. Santa FÈ: Bear and Co.

Gablik, S. (1991). The Re-enchantment of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Goodwin, B. C. (1999). From Control to Participation via a science of Qualities. Revision, 21(4), 26-35.

Hafiz. (1999). The Gift: Poems by Hafiz, the great Sufi Master (D. Ladinsky, Trans. ). New York: Penguin Compass.

Harding, S. P. (2001). Exploring Gaia. Resurgence, 204, 16-19.

Harman, W. (1988). Global Mind Change: the promise of the last years of the twentieth century. Indianapolis: Knowledge Systems.

Hawken, P. (1993). The Ecology of Commerce: a declaration of sustainability. New York: HarperBusiness.

Hawken, P. , Lovins, A. B. , & Lovins, L. H. (1999). Natural Capitalism: The next industrial revolution. London: Earthscan.

Jay, P. (2000). Let the Poor Seek Their Place in the Sun. New Statesman, September, 17-19.

Korten, D. C. (1999). The Post-Corporate World. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Leakey, R. , & Lewin, R. (1995). The Sixth Extinction: biodiversity and its survival. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Lovelock, J. E. (1979). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. London: Oxford University Press.

Macy, J. R. (1991). Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory: the Dharma of natural systems. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Marshall, J. (1999). Living Life as Inquiry. Systematic Practice and Action Research, 12(2), 155-171.

Midgley, M. (2001). Gaia: The next big idea. London: Demos.

Orr, D. W. (1994). Earth in Mind. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Reason, P. , & Torbert, W. R. (2001). Towards a Participatory Worldview Part 2. ReVision, 24(2), 1-48.

Robertson, J. (1998). Transforming Economic Life: a millennial challenge. Totnes, Devon: Green Books Ltd. Rorty, R. (1999). Philosophy and Social Hope. London: Penguin Books.

Shiva, V. (2000). Earth Family. Resurgence, 199, 16-17.

Toulmin, S. (1990). Cosmopolis: the hidden agenda of modernity. New York: Free Press.

Whitehead, A. N. (1926). Science and the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

www.bbc.co.uk/arts/news_comment/dimbleby/print_clinton.shtml

- Publication date:

- Modified date:

- Categories: 2002 Other Articles Peter Reason

-

Western Chan Fellowship CIO

Western Chan Fellowship CIO - Link to this page

©Western Chan Fellowship CIO 1997-2026. May not be quoted for commercial purposes. Anyone wishing to quote for non-commercial purposes may seek permission from the WCF Secretary.

The articles on this website have been submitted by various authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Western Chan Fellowship.

Permalink: https://w-c-f.org/Q372-605